Rujuta Damle, 26, first heard of breast milk donation in her teens. But it was only last year that she found herself empathising with the cause. During her pregnancy, Damle, a Pune resident, had enrolled for pre-natal classes at the Deenanath Mangeshkar Hospital. The last session of the course was a tour of the labour room, where Damle came across an infant who had a hole in his heart. “The child was taken into the newborn care unit. We were told that he would have to wait for breast milk, crucial for his survival, since his mother was hospitalised in a different hospital. It was a disturbing experience... heartbreaking,” says Damle, a chartered accountant.

So when Damle had her daughter, she decided to donate the extra milk she had to a human milk bank at the hospital. Damle has been doing so for the past five months—after her daughter has had her fill, she pumps out the extra milk in 150ml bottles she receives from the hospital. Once the bottles are full, the hospital has them collected from her home. “The nurses and the doctors explained every little thing that I need to take care of while storing the milk in the deep freezer,” she says.

Damle is one of the few mothers donating for the 30 milk banks across the country. Twenty-seven million babies are born in India every year and, of them, 13 per cent are born pre-term, and 28 per cent have low birth weight. Experts say human milk is high on the charts to save these children who are too weak to suckle and their mothers are unable to provide milk—either they are ill, or dead, among other reasons. Here, milk banks that collect and store human milk come in handy, say doctors.

The ministry of health and family welfare is planning to scale up the milk bank model for the 661 newborn care units in the country by introducing new guidelines. It will encourage mothers to donate extra milk to a lactation management centre [that will have breastfeeding support activities, including milk bank], says Dr Ajay Khera, deputy commissioner, ministry of health and family welfare. “Hospitals will be provided with equipment such as pumps for mothers to express milk. There will be quality control mechanisms to test the milk for pathogens, and pasteurisers and refrigerators for storage,” says Khera.

Human milk banks have been extremely successful in Brazil—its network of human milk banks is the largest in the world—and have helped the country bring down its neo-natal deaths and infant mortality significantly. In India, the first and one of the most successful banks was started in 1989 at Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital in Mumbai. The bank was started by Dr Armida Fernandez, who was driven by a desperate need to save sick babies at the hospital. It worked because mothers who had delivered at the hospital and those who came for a follow-up were encouraged to donate. “Initially it was hard to convince the municipal corporation to fund the bank. But somehow we managed to do so. We were also able to convince mothers to donate,” recalls Fernandez, former professor and head of neonatology at the hospital.

The success of the bank, however, did not prompt others to follow suit—until 2005, when a few hospitals started their own milk banks. Today, there are milk banks in New Delhi, Hyderabad, Chennai, Pune and Surat that follow different models of funding, collecting and storing donor milk. For instance, in the bank started by Fernandez, the milk was collected at the hospital, but in Amaara, the milk bank at Fortis La Femme in Delhi, and the one at Deenanath Mangeshkar Hospital, the milk is collected from the donors’ home.

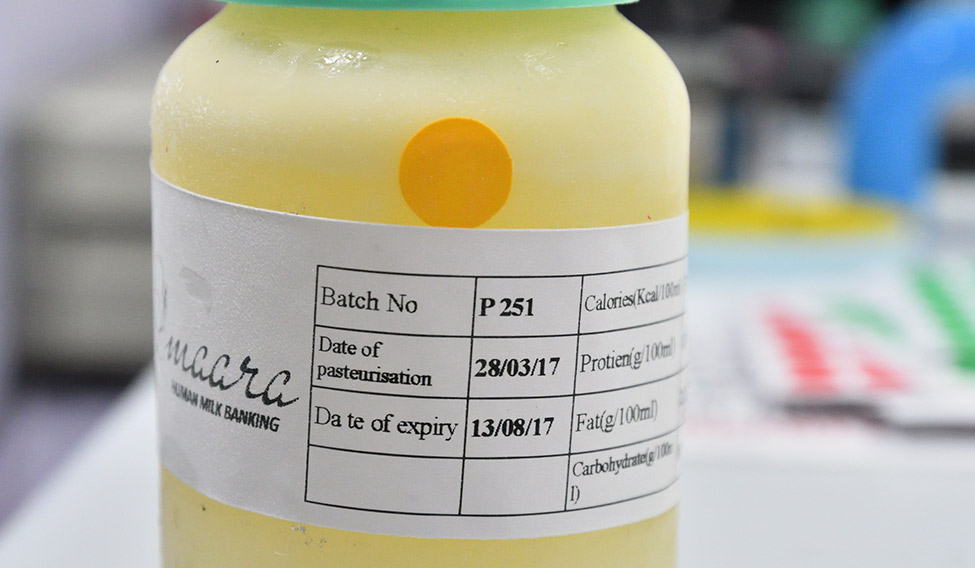

After collection, the milk is tested, pasteurised to kill germs, stored and given out on doctor’s prescription only, says Dr Raghuram Mallaiah, director, neo-natology, Fortis La Femme. The details of the contents—fat, protein and number of calories—and the donors are recorded and stored in a database to ensure quality. “We are a public bank and supply to the newborn care units at other hospitals, too. We charge a nominal amount. So making the bank self-sustainable is a big challenge,” says Mallaiah, who sourced funds from the Breast Milk Foundation, a non-profit organisation founded in 2015, to set up the milk bank last year.

But human milk banks can be cost-effective, too. Back in the 80s, Fernandez says that the cost of setting up a milk bank—02 lakh—worked out to be less than that of installing a ventilator in the hospital. Today, a human milk bank costs 012 lakh, excluding staff costs, says Ruchika Sachdeva, who heads the nutrition department at PATH, a non-government organisation that is providing technical support for cost-effective indigenous pasteurisers available in India.

In the US, human milk is often termed as ‘liquid gold’ and mothers sell their milk to private banks. In India, however, the emphasis is on promoting it as an altruistic act. “Commercialising breast milk could be dangerous because of quality issues involved,” says Khera.

The importance of human milk banking can hardly be overstated. Despite several studies on the benefits of human milk as opposed to formula feed, awareness on the issue is still low, and breastfeeding rates stand at 54.90 per cent only, according to National Family Health Survey for 2015-16. “The rate of institutional deliveries is high, but the same cannot be said about breastfeeding. In ten years, early initiation [giving mother’s milk within one hour of birth] has increased from 23.4 per cent to 41.6 per cent, reveal the survey data. But the rise is only about 1.5 per cent every year,” says Dr Arun Gupta of Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India. Providing donor milk through human milk banks works only if it is part of the larger agenda of promoting breastfeeding, he says.

Adhunika Prakash, founder of Breastfeeding Support for Indian Mothers, an online group that provides round-the-clock support to close to 40,000 members, says mothers are misinformed about breastfeeding. “In my group, half the women have given formula to their kids at birth,” she says. “Breastfeeding can be a stressful experience, and women need support from doctors, lactation counsellors, hospital staff and family members.”

Elixir of life: A bottle of pasturised human milk | Sanjay Ahlawat

Elixir of life: A bottle of pasturised human milk | Sanjay Ahlawat

That is why the upcoming guidelines, which are part of a breastfeeding promotion programme called MAA (Mothers Absolute Affection), show promise. Sachdeva insists that the lactation management centres will serve not just as providers of human milk through donors, but also as “welcoming hubs” for mothers. “This integrated approach will provide breastfeeding support and encourage kangaroo mother care [skin to skin contact], too,” she says, adding that increased access to donor milk would help 5 million vulnerable newborns in India.

Bengaluru-based Charulatha Varadarajan, 36, can think of at least two—her twins, who are four now. Varadarajan's kids were born early and put on formula feed right after because she was unwell. “After I started expressing milk, I often had extra. But the hospital didn’t have a bank to store it,” she says. “If it did, the milk could have helped other pre-term kids.”

Banking norms

* Human milk banks will be part of lactation management centres, where women would be given support for breastfeeding, kangaroo mother care and encouraged to donate milk.

* Milk banks would be established in tertiary care hospitals, and smaller hospitals would serve as collection centres.

* Standards of quality will be mentioned in detail. High focus on hygiene and handling of milk.

* Hospital staff will be trained for hazard analysis and critical care points (HACCP) systems. Pasteurisation techniques and temperature for storage will also be mentioned.

* Donor mothers will be screened for HIV, syphilis and hepatitis B.

* The donors would not be paid for the milk, and milk would be given only on doctor’s prescription.