Those were bad days—the sixties.

In 1962, the Chinese gave us a bad drubbing. The stature and reputation of Jawaharlal Nehru, the idealist leader of idealist India who used to preach peace and pontificate on non-alignment to the world, were in the pits. The morale of the armed forces was at its nadir. Army chief P.N. Thapar had been sent out on health grounds, and then packed off as ambassador to Kabul, and General J.N. Chaudhuri, an uninspiring figure, had taken over.

India was beginning to burn. The Sikhs of Punjab began to seek a separate homeland for themselves. A demand from the Hindi fanatics to impose Hindi on Indians led to widespread protests in the south, even leading to fears of separatism. Dravidian leader C.N. Annadurai was arrested and sent to jail for insulting the national flag. There was not enough food for the people to eat. Food riots rocked several states. So did communal riots.

In 1964, Nehru died.

There was a huge vacuum at the top. There was no leader who seemed tall enough to succeed him. A syndicate of Congress leaders put up Lal Bahadur Shastri, a simpleton whose only qualification seemed to be that he was harmless and they could control him, as prime minister. He knew no world leaders, did not understand diplomacy, and spoke Ganga-kinarewala English. When told that there was not enough food, he told the people to tighten their dhotis and pyjamas.

In 1964, China tested a nuclear device.

India was shocked. The enemy who had humiliated us just two years before was entering the big league of the Americans, the Russians, the British and the French. India, which had been riding high under Nehruvian utopianism, was being shown its place in the comity of nations—among the poor, the third world, the weak, the humiliated, the wretched and the damned.

Homi Bhabha, the visionary scientist who had remained like a leftover from the Nehruvian Camelot days, urged Shastri to let him test a nuclear device, at least to tell the world that there still was life left in India. But Shastri “chickened out”.

No guts, the world concluded.

Across the Radcliffe Line, in Pakistan, the picture was exactly the opposite. A dashing six-foot Pathan general, trained in Sandhurst and battle-hardened in the jungles of Burma in World War II, had taken over the country. He spoke impeccable English, understood global power politics, drank Scotch with Harold Wilson, patted the six-footer Lyndon Johnson on his cheek (there is a photo of him doing that), and shook hands with Comrade Mao. He had got Patton tanks from Eisenhower, Sabre jets from Kennedy, and assurances of continued supply of guns and ships from Wilson.

The move to befriend China was Ayub's shrewdest strategic move. He spotted the opportunity soon after the Chinese invasion of India. He knew that if he could do it, he would be the only world leader who would be an ally of both the capitalist world and of an emerging communist power. A masterstroke in power diplomacy. Only Russia remained cold towards him, but he didn't bother—for the Russians were not being too friendly with India either. They had given India a few MiG-21s to defend themselves against the Chinese, but the Indians themselves were not very good at flying those supersonics.

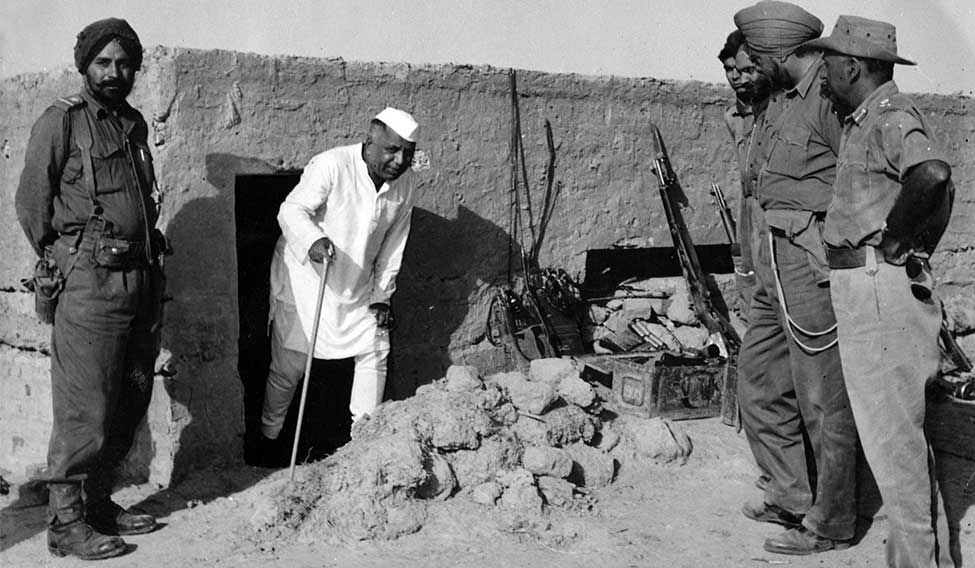

The first strike: Pakistani soldiers manning a position in the Rann of Kutch | Getty Images

The first strike: Pakistani soldiers manning a position in the Rann of Kutch | Getty Images

Shastri looked to the west for help. American and British diplomats came in hordes to lure India, offered wheat and warplanes, but they all had just one or two options to offer. Forget Nehru's woolly-eyed non-alignment, and join our alliance. Some even suggested: cede away Muslim-majority Kashmir, make up with Pakistan and let us together take on the communist baddies who had invaded you.

Kashmir, over which India and Pakistan had fought a war immediately after the birth of the two nations, was still a bone of contention. The British had left the issue unsettled at the time of the partition. Despite there being a standstill agreement, Pakistan had sent in its troops disguised as tribal raiders to invade Kashmir in September 1947. The ruler of Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh, had acceded to India and asked for military help. The Indian Army had thus landed in Kashmir and pushed back the Pakistani raiders, but a UN-ordered ceasefire in 1948 had led to Pakistan holding a third of the state.

Since then, Pakistan had been asking for the remaining two-thirds. India's arguments—that it was Pakistan that had attacked Kashmir first in 1947, violating the standstill agreement; that India had sent troops only after the helpless maharaja had appealed for help; and that even a UN-mandated plebiscite could be held only after Pakistan vacated the one-third of Kashmir it had occupied in 1947-48—were falling on deaf ears.

Several rounds of talks had been held between India and Pakistan over Kashmir during Nehru's time, but there had been no meeting ground. Every time, Pakistan had resorted to commando-style diplomacy. For instance, just when the Indian delegation reached Rawalpindi for talks in December 1962, Pakistan announced that it had ceded part of the Kashmir territory it had been holding to China. (Only a month earlier had China invaded Indian territory and annexed a portion of Kashmir adjoining the territory that Pakistan had now ceded.) The new foreign minister of Pakistan, the ambitious Z.A. Bhutto, proved to be far too polemical, assertive and even acerbic compared with the descriptive and ambulatory Sardar Swaran Singh of India. The negotiations finally broke down on May 16, 1963, about a year before Nehru's death.

It looked Shastri was tempted to bite the western bait. President Johnson invited him to Washington. But he cancelled the invitation when Ayub protested. A miffed Shastri instead went to Canada and, as Ambassador K.P. Fabian mentions in Diplomacy: Indian Style, “refused to take a call from the White House when he was there.” On the way back, Shastri stopped over in Karachi for a private meeting with Ayub, who later recorded that he raised the Kashmir issue, but Shastri told him that he was not yet “strong enough” to carry “his people” with him towards renegotiation of the Kashmir dispute.

As Stanley Wolpert commented later, “Ayub was personally convinced after seeing frail little Shastri that his Indian counterpart was too enfeebled to respond with more than a whimper to any frontal assault or outright war.”

But the crafty Ayub, trained in the best military schools, knew he should not strike in Kashmir. One of the first lessons that is taught in military schools is to strike where the enemy does not expect. Ayub did exactly that. He struck in Gujarat, in the Rann of Kutch, the border of which had been disputed between India and Pakistan, but “a virtually uninhabited region of mudflats and wasteland” 515km long and 80km wide, “economically and strategically useless”.

The run into the Rann

On a January morning in 1965, a few constables of the Central Reserve Police in the Rann found that Pak border guards had been patrolling the track they had been using. Next they found a Pak post in Kanjarkot, 2km within India. They promptly set up their post at Vigokot and Sardar, 10km southeast of Kanjarkot.

The watch never ends: The Camel Corps of the Rajasthan Armed Constabulary patrolling near the border | Getty Images

The watch never ends: The Camel Corps of the Rajasthan Armed Constabulary patrolling near the border | Getty Images

One thing led to another, and in early April, the CRP struck at a Pak position near Ding. On April 9, two Pak army battalions of about 1,400 men attacked Indian positions. The next day, India announced that it would counterattack with its Army units. On April 24, Pakistan's Patton tanks rolled more than seven miles into the dry Rann and cannonaded Indian posts for a full week.

Pak commanders found the operation as easy as cutting through butter. Ayub had chosen his battlefield cleverly. His troops on the front could be serviced through better roads; from the Badin cantonment, he could quickly send supplies. On the other hand, India had no roads in the sector to support operations. Pak newspapers even reported that Indian troops and tanks just fled at the sight of a Pak gun. Later Ayub would boast to friends in London that he could have destroyed an entire Indian division if he had wanted, but just let them go.

By the time India sent reinforcements to its embattled units in the Rann, the monsoon had arrived. The Rann was flooded. Not even infantry movement, let alone tank movement, was now possible. The overcautious General Chaudhuri finally moved troops into Punjab, but they did not cross the border. The move was perceived to be aimed at placating public opinion.

Most world leaders asked Britain, still the most influential foreign power over the subcontinent, to intervene. Prime Minister Harold Wilson got Shastri and Ayub to talk to each other at the Commonwealth conference in London in June. Ayub showed a military brashness in his conduct there, too. When the Indian side gave diplomatic papers, Ayub retorted contemptuously, “I can't understand all this writing, bring me a map.” (Years later, a successor of his, Pervez Musharraf, also a general, would wreck the Agra summit calling diplomatic statements as “one and a half pages of English composition”.) Finally, on June 30, the two signed the Kutch-Sind pact, agreeing to restore status quo ante, but Pak troops would be allowed to patrol the road near Kanjarkot.

Shastri and Ayub also agreed to refer the dispute to a three-man tribunal. The two foreign ministers also agreed to meet on August 20, because Bhutto said, a bit too snootily, that he could not be free before mid-August.

The first act of deception! He knew that, before August 20, Ayub would have invaded Kashmir.

The deception

On the hot afternoon of August 5, Kewal Singh, India's new high commissioner designate to Pakistan, landed in sultry Karachi. He had another five days to unpack and get ready; the presentation of credentials ceremony was fixed for August 10.

But, as soon as he landed in Karachi, Kewal Singh received a message: as a special courtesy, Ayub would receive his credentials the very next morning.

Overnight, credentials papers were sent by a special courier from Delhi, and the next morning Singh, ceremonially dressed for the occasion, presented himself before Ayub. The president received him with all courtesy, spoke how he wanted the relations between the two countries to progress well, rued how the two were wasting money on arms, blah, blah, blah.

It was the second act of deception. For, he knew, and Kewal did not, that 12 hours earlier, thousands of Pak guerrillas, trained by Major-General Akhtar Hussain Malik, commander of the 12th division of the Pak army, had crossed the ceasefire line and were heading towards Srinagar. Operation Gibraltar had opened.

Relishing the victory: Indians celebrating on top of a Pakistani tank captured during the war | Photo Division, Ministry of Defence

Relishing the victory: Indians celebrating on top of a Pakistani tank captured during the war | Photo Division, Ministry of Defence

“It is obvious that Ayub desired to get the formal accreditation of the Indian high commissioner over before the news about Pakistan infiltration into Kashmir reached the world at large…,” wrote J.N. Dixit in India-Pakistan in War & Peace later. “The Indian high commissioner not presenting his credentials because of the conflict might have let the cat out of the bag.”

Ayub and Bhutto had timed the operation well. For, Kashmir was already in turmoil and boiling over with anti-Delhi protests. A year earlier, in August 1964, Sheikh Abdullah, who had once struggled against the secessionist-minded Dogra rulers to get Kashmir for India, declared that independence was the only solution for the Kashmir problem. In September 1964, he even called for use of force to achieve it. And, in early 1965, he went on a world tour—London, Algiers, Mecca—and announced that he would soon go to Peking to elicit China's support for Kashmir cause. These moves were perceived in India as an effort to seek the assistance of India's enemies. On May 8, on his return to Delhi from the world tour, Sheikh was arrested under Defence of India Rules and packed off to Ooty in Madras state, where he was kept in confinement. The Kashmir valley erupted in protest.

Ayub and Bhutto had calculated that it would be a smooth walk for the guerrillas into Kashmir, where the protesting Kashmiris would aid them. The plan was for the guerrillas, about 1,50,000 of them divided into eight forces, to raid military bases in Kashmir and take over civil administration offices, blast bridges and roads, ambush Indian Army columns in small numbers, capture the Srinagar radio station, and install a Revolutionary Council, with a few local Kashmiris in it.

Everything worked according to plan. About 30,000 guerrillas crossed the ceasefire line on August 5-6, a few hours before Kewal Singh marched into the presence of Ayub Khan to present his credentials. The Indian Army patrols were overwhelmed, and they fell back.

But what the raiders had not anticipated was the fierce independence spirit of the Kashmiris. Much as they wanted to be independent of Indian control, the local Kashmiris did not like to be part of Pakistan either. As General Chaudhuri wrote in his Arms, Aims and Aspects, “None of the infiltrators were Kashmiris. This broke the first principle for the guerrillas. South of the Pir Panjal, it was a little more successful, as the ethnic groups were similar and some of the infiltrators came from the area itself.” The valley people, who had been protesting against the arrest of Sheikh, now began alerting the Indian Army and informing them of the movements of the guerrillas. The guerrillas “failed in their mission because of local resistance from the people and by the locally supported Indian security forces,” wrote Dixit. “It became clear to the Pakistani authorities that the use of force in a clandestine form was failing.”

But there still was little military resistance from the Indian side, which did not have the time to consolidate. The Army continued to be ambushed, fired upon and, in most places, unable to fight back in strength. From August 5, wrote Pauline Dawson in The Peacekeepers of Kashmir: The UN Military Observation Group in India and Pakistan, “India began to complain of attacks, mainly on bridges, military convoys and isolated picquets, but also increasingly on local headquarters…. UN Observers themselves saw mortar and grenade explosions and light machine gun fire directed at two bridges one and a half miles south of their location and four miles on the Indian side of the Ceasefire Line on the main Poonch-Jammu road.”

When India raised the issue on international fora, Pakistan responded that it was a local uprising in India-held Kashmir. By August 7-8 night, the town of Mandi near Poonch was taken by the guerrillas. There were attacks on Kargil, Baramullah, and the main force of guerrillas headed towards Srinagar.

Three years after the loss to the Chinese, it looked the Indian Army was going to lose again. Then came a real morale-booster.

Alleging that some 20 guerrillas had attacked an Indian picket with the support of machine gun fire from across the ceasefire line, a battalion of Indian troops blasted across the line, kicked out the Pakistani pickets there and captured three posts from where the Pak troops had been firing at the Srinagar-Leh road. “It was a difficult military operation, for the attackers had to scramble through a huge, unswept rock wasteland, commanded by Pakistani guns,” wrote Russel Brines in The Indo-Pakistani Conflict. “One of the captured posts was perched at 13,600ft on a barren rock ledge; the others were nearly as inaccessible.”

The action might look a minor one today, but it was big then. For this was the first time that the Indian Army showed signs of aggression after 1947-48. And once they occupied the posts, they refused to vacate them.

The UN ceasefire observer, the Australian Lt-Gen R.H. Nimmo, was taken aback. He asked the troops to vacate. We are here to stay, they told him. Nimmo called up Gen Chaudhuri. The reply was a firm no.

Deft as much at diplomacy as in the battlefield, Ayub spotted a chance to call India the aggressor. Many in the world were willing to believe because, for all their aggression over the years, the Pakistani troops had rarely violated the ceasefire line in their uniform and encroached upon Indian territory. All their aggression and needling of India had been by proxy, using the ‘tribal’ guerrillas who were ‘working’ for liberating their Kashmiri brethren from Indian occupation. Officially, the Pak army had never been involved.

But, by now, the Indian Army was not concerned about niceties. Firing became routine across the ceasefire line. By June 8, Gen Nimmo reported that Indian troops were holding a new front of approximately 24km along the ceasefire line, which was a violation of the Karachi agreement.

The general in Ayub was quick to realise the gravity of the situation. The Indian troops, he understood, could mount guns on the posts they had captured, and guard the supply lines to Ladakh, and also launch a major offensive into the Northern Areas, peopled by the fiercely independent tribesmen who had never agreed to be part of Pakistan or even Kashmir.

By the end of August, three things became clear to Ayub. One, the revolt was failing. The guerrillas had been confined to an area just 16km deep along the ceasefire line. Two, Indian troops were showing guts, at least in isolated pockets. Three, his own territory, the Northern Areas, could be in danger if they were not checked.

The job now, he realised, was not for the ragtag guerrillas. It was a job for the boys from the military schools—the ones who drove Patton tanks and flew Sabre jets.

In safe hands: A child injured during Pak bombing being treated at a hospital in Punjab | Getty Images

In safe hands: A child injured during Pak bombing being treated at a hospital in Punjab | Getty Images

The war

One of the UN observers travelling from Rawalpindi to Bhimber spotted them on August 31—three squadrons of Sherman tanks, tank recovery vehicles, one infantry battalion and some medical units ready for attack. He sent a report to his headquarters, where it was received on September 2.

UN observers' messages travelled slow those days. They were not allowed to use the telegraph or the wireless, because those could be picked up by either side. The reports had to be couriered.

Ayub's Shermans were faster than the observers' couriers. On September 1, about 70 Shermans rolled along with two brigades of about 4,000 troops into the Chhamb district, where the ceasefire line ended and the international border began in Jammu & Kashmir.

Operation Grand Slam opened.

The aim was clear: cut the main communication lines between Jammu and Poonch, and Jammu and Srinagar. Once the lines were cut, Indian Army units in the valley would stop receiving supplies from Jammu and the rest of India. The guerrillas, pretending to be local revolutionaries, would then overpower the Army units, take over civil installations, declare independence and form a revolutionary government. Pakistan then would be seen only as aiding a liberation regime, which had appealed for its help.

The ferocity of the attack took about 1,000 Indian troops stationed in Chhamb by surprise. They fell back. The Shermans drove straight to Akhnoor, 32km inside India, with the objective of capturing the bridge across the Chhamb river and thus cutting India's supply lines into the valley.

As soon as the report about the attack reached the Army headquarters in Delhi, India realised the gravity of the situation. Once the Shermans captured or destroyed the bridge, Pakistan would launch a second attack towards Jammu city. “The conquest of Jammu would have severed the second main road into northern Kashmir, thus cutting land communications and isolating the Indian Kashmir garrison,” wrote Russel Brines. That would have completely isolated the Indian army in Kashmir, which would then have been overwhelmed and destroyed.

Though overwhelmed by numbers and the ferocity of the attack, a small contingent of the Indian Army fought back. The C squadron of 20 Lancers prevented the enemy from capturing the bridge.

But the signs were bad. It was the route through which most of the dreaded invaders had come—Alexander, Mahmud Ghazni, Babar, Nadir Shah and Ahmed Shah Abdali. By 11am, the embattled brigade in Chhamb reported that they could not hold on, and asked for air support. That needed the cabinet's permission, as bringing in the Air Force to bomb enemy tanks could escalate the war.

Chaudhuri, who was in Kashmir, flew back to Delhi. On the way, he stopped at Pathankot, where the station commander told him that he could provide air support. At 4.45pm, he called on defence minister Y.B. Chavan along with Air Marshal Arjan Singh. Together they asked for sanction to use air power.

The best in Chavan came out at that moment. He realised he did not have time to consult the emergency committee of the cabinet. He realised he did not have time to consult even the prime minister. At 4.50pm, Chavan gave his decision: go ahead.

At 5.19pm, 26 Air Force fighters roared into the western skies. But it looked to be an uneven struggle. For most of those 26 were obsolete Vampires and a few Mysteres, fitted with close-range guns. Against them would be pitted brand-new F-104 Starfighters and F-86 Sabre jets, which shot longer-range air-to-air missiles.

Four of those 26 did not come back.

But the mission was not a failure. They had pounded the Shermans from the air, and slowed them down, though they could not halt them.

On September 2, Arjan Singh put his squadrons of puny Gnats to battle. The first news was bad. Squadron Leader B.S. Sikand, on a Gnat on September 3, had a dogfight with a few Sabre jets, and lost his way. As he ran out of fuel, he spotted an airfield and landed there. Only to discover that he had landed in Pasrur in Pakistan.

But the good news came soon. His colleague Squadron Leader Trevor Keelor, flying another Gnat, shot down a Sabre, electrifying the nation (see story on page 44). Chavan wrote in his diary, “This day began with a gift from IAF. CAS came to my residence with a [sic] news that IAF in the morning air battle had shot down an F-86 of Pakistan in the Chhamb area.”

The next day, September 4, Flight Lieutenant V.S. Pathania, flying another Gnat, shot down another Sabre. The Sabre kills put the Pakistan air force on the defensive. But Ayub's army rolled on.

On September 4, China's foreign minister ‘stopped over’ in Karachi for six hours and talked to Bhutto. He stated officially that China would back the “just action taken by Pakistan to repel the Indian armed provocation”. India worried.

The next day, the PAF was again in high spirits. A single Sabre jet roared into Indian Punjab and knocked off anti-aircraft radars and guns near Amritsar. A new front was opened; the war was taken away from Kashmir into Punjab.

Shastri, Chavan and Chaudhuri were looking for the excuse. They knew that they could not hold on in Kashmir. The only way to dissuade Pakistan was to hit it somewhere else. The Sabre strike near Amritsar provided exactly that.

Defence minister Y.B. Chavan at Barkee near Lahore, where the Indian Army secured a decisive victory | Photo Division, Ministry of Defence

Defence minister Y.B. Chavan at Barkee near Lahore, where the Indian Army secured a decisive victory | Photo Division, Ministry of Defence

At first light on September 6, the plains of Punjab were woken up with the huge roar of three full divisions of Indian Centurion and Sherman tanks driving all along the border deep into Pakistan territory, and racing towards the fabled city of Lahore, which India had always coveted. And, before the Pakistani general staff could recover from the shock, they heard that another Indian armoured formation was rolling rapidly towards Sialkot, an important road and rail junction.

India attacked.

Shastri was becoming the ‘aggressor’, but he did not mind the tag. The world condemned India. But that was easily explained. “The principal reason was probably that India carried out her operations with relative openness while Pakistan employed subterfuge with considerable success,” pointed out Brines. But then “foreign criticism hurt the Indians, infuriated them and intensified their determination”.

Even India was taken by surprise by Shastri's bold stroke. Indeed, the Army had always war-gamed that they would have to strike across Punjab if the Pakistani pressure on Kashmir became too unbearable; all the same, no one expected it to really happen. Not even foreign secretary C.S. Jha. In fact, Shastri had sent Jha to New York on September 4 to take care of the crisis in the UN Security Council.

Ayub was furious. The puny Lala had outsmarted his military genius. He now had to choose between two options—either to risk losing Lahore and Sialkot and capturing Akhnoor (and thereby Kashmir), or give up Akhnoor (and Kashmir) and rush his tanks to save Lahore and Sialkot.

Ayub chose the latter. He ordered his tank formations that had been driving towards Akhnoor to turn around and drive south to stop the Indian tanks racing towards Lahore and Sialkot.

On the night of September 8, Ayub launched a counterattack on five fronts with more than 225 Patton tanks towards Khem Karan, with an aim of reaching the rear of India's advancing columns so as to cut their supplies. Once that was done, he calculated, the same columns could roll down the Grand Trunk Road towards Delhi.

It was now the Indian Army's turn to claim its share of glory, after the Air Force and the political leadership had shown perfect sense of timing and strategy. But incredibly, Gen Chaudhuri permitted his formation commander to withdraw his armour and infantry from Khem Karan. Was the Indian Army caving in?

It was a trap.

As the Indian armour withdrew from Khem Karan, Pakistan's Pattons drove into a huge horseshoe-shaped field near the village of Assal Uttar. As they drove in, the Indian Army opened the dykes and small dams built on the streams and canals flowing through the region. The entire region became waterlogged, and several Pakistani tanks got stuck in slush and the mud.

Caught by surprise, the Pak tanks tried to crush into a dry sugarcane field nearby which sported full-grown cane. Little did they know that a force of Indian Centurions and Shermans was crouching in ambush behind the tall sugarcane bushes.

When the Pak tanks rounded a corner of the fields and exposed themselves, the Indian tanks opened fire. As one column of Pak tanks tried to outflank the Indian armour, the IAF pounded from the air. The Pak forces fell back to Khem Karan. In the battle, India destroyed 60 Pak Pattons, and captured 10 intact. Later estimates said India destroyed or captured 97 Pattons.

By September 10, India's Centurions, despite being blind at night without infrared sights, unlike Pakistan Pattons, were leaning on the defences of Lahore. The airport was just 6.5km from the Indian front, when the Americans appealed for a short quiet, so that they could remove their nationals from Lahore.

Further north, the battle for Sialkot was raging—a tank battle that would come to be recorded as the biggest since World War II. It raged for 15 days, with 400 Indian tanks (Ayub said there were 600) being blocked by superior Pakistani armour. If the Indian objective was to capture Sialkot and cut the entire Pakistani military movement further north, it failed. The Pakistanis put up stiff resistance and Sialkot remained elusive to the Indian commanders.

However, the official Indian version is that capture of Sialkot had never been India's objective. The thrust towards the city was only a diversionary attack mainly to draw the Pakistanis away from Chhamb and keep them engaged, as also to destroy Pakistani military equipment and prevent another thrust.

The lull after the storm: Indian soldiers at a captured village in Sialkot sector in Pakistan | Photo Division, Ministry of Defence

The lull after the storm: Indian soldiers at a captured village in Sialkot sector in Pakistan | Photo Division, Ministry of Defence

All the same, since this 15-day battle was the main engagement in the war, and because it was fought in Pakistani territory, India could claim that Pakistan was the loser in the war. But the same argument has been used by Pakistan to paint India the aggressor and thus claim to have successfully defended their city and territory.

Meanwhile, in the south, the Indian offensive towards Lahore had weakened. Here, too, the Indian side claimed that capture of Lahore was never India's objective, and that it knew that a city captured was a big burden on the conquering army's military resources. The world over, militaries avoid capturing and holding on to cities knowing full well that they get tied down there, and lose their battle-readiness. At the most, the Indian objective was to surround Lahore.

As the ground war slowed down, the air action continued unabated. Having downed two Sabres and then having struck at Sargodha on September 7, destroying nearly a sixth of the air assets there, Arjan Singh put the PAF on the defensive. He ordered the heavy-duty Canberras, his favourites, into action at the advancing Pak tank formation everywhere. As Air Commodore Jasjit Singh wrote in the authorised biography of Arjan Singh, “throughout the war, no Canberra on daylight bombing was shot down or even damaged by the PAF”.

By then, the PAF had realised that Indian defences were largely concentrated in the west, and began attacks from East Pakistan. Kalaikunda in Bengal was attacked first. When the PAF Sabres came again, two of them were downed by Hunters. The PAF retaliated with attacks on Agartala and Barrackpore. Now the IAF sought permission to strike back on bases in East Pakistan. “I told him to wait for a day,” Y.B. Chavan wrote in his diary. “One more incident, and he is free to go ahead.” Maybe the Pakistanis read Chavan's mind. That one more incident did not happen.

Both sides seemed to be cautious, and they seemed to want to avoid bombing of civilian areas in each other’s cities. India was estimated to have lost 65 to 70 planes, whereas Pakistan, which employed fewer of its planes, lost 20.

Anyway, after the initial thrust, the Indian ground offensive slowed down. Moreover, as the battle of Sialkot raged, India had to move several regiments of tanks from the Lahore front to the Sialkot front. It was here that finally Gen Chaudhuri proved to be a brilliant tactician. With the limited resources at his disposal and inferiority in the quality of equipment, he managed to fight on two fronts, at least to prevent the Pakistani armour from getting on the high road to Delhi. For, if the Indian formations had not tied down the Pakistani armour outside Lahore and Sialkot, the enemy’s main body would have entered Indian Punjab in full force and rushed towards Delhi.

The major part of the war was these two tank engagements, which lasted nearly a fortnight with neither side being able to move much forward. But there was movement, indeed far faster, in the air. In the Chhamb sector, the Army continued to need air support, but the official history does not mention the nature of air support given in Chhamb. All the same, accounts from Pakistan have confirmed that the IAF prevented a major breakthrough by Pak army in Chhamb.

One thing that most commanders dread, next only to defeat, is prolonged stalemate. That is when the military mind, which abhors inaction, gets frustrated. The stalemate in this war, too, began to bring out the frustrations that had been there in the military minds. One sign was the friction developing between the services. Both the Army and the Air Force were new to this kind of joint operations. At times, there was collateral damage and the two services blamed each other. The Army complained that the IAF was not checking its presence in the target area they were bombing. The IAF complained that the Army still did not know the rules of camouflage. On one occasion, the troops were so scared to advance, fearing that bombs from IAF aircraft would fall on them, that Lt-Gen Harbakhsh Singh had to upbraid the commander of 15 division.

The stalemate in the ground war also brought out intra-service tensions. At one meeting in the operations room, in the presence of the chiefs of the Air Force and the Navy, Lt-Gen M.S. Pathania, the adjutant-general, is said to have flared up against his chief for being “a political general” and “not a professional soldier”. Finally, the air chief had to pacify Pathania and lead him out of the room.

As the ground war thus ground down, both sides claimed victory. However, wrote Brines, “the consensus of informed foreign opinion was that the conflict resulted in a draw. In terms of equipment, military circles in Washington concluded, on the basis of post-war information, that Pakistan lost 200 tanks, with another 150 put out of action but recoverable. India, by this assessment, lost between 175 and 190, with another 200 temporarily out of commission.”

By now, the peacemakers were getting active. Washington, though more friendly towards Pakistan than towards India, was not happy with Ayub's overtures towards communist China. Meanwhile, it was clear to all that India was keeping the main body of its Air Force in the east for fear that the Chinese would intervene there. The US had to prevent this. Secretary of State Dean Rusk publicly warned Peking to stay out of the conflict and US ambassador to the UN John Cabot warned that if China intervened, the US would retaliate.

For once, the US and the Soviet Union seemed to be working in tandem. They refrained from vetoing each other in the Security Council. On September 20, the council demanded a ceasefire on the morning of September 22, and a subsequent withdrawal of troops to the positions of August 5. By then, Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin had invited Shastri and Ayub to a political summit in Tashkent.

The big powers—the US, the USSR, Britain and France—seemed to be working with one major concern in their minds: to prevent communist China, which was then not a member of the Security Council, from interfering in the conflict. In fact, the council’s resolution even warned against it. It called “on all states to refrain from any action which might aggravate the situation in the area”.

The war ended there, and diplomacy took over.