Outside the arrival gate at the Paro airport, the only international airport in Bhutan, I was greeted by a gush of wind on August 11. It was, however, not too cold, and thick clouds were kissing the surrounding hilltops. As the taxi reached the outskirts of Thimphu, the capital city 48km away, it started raining heavily. And the lush green hills glittered like a string of pearls.

Bhutan has been witnessing a glittering transition over the past decade. Once a conservative monarchy, it made a smooth switch to democracy in 2008. Three years ago, the country witnessed a dramatic break from the past as the young king, Jigmey Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk, publicly kissed his wife, Jetsun Pema—twice on her cheeks and once on the lips. The king’s public display of affection hinted at a big change in the Himalayan kingdom.

Some of the changes are quite visible. I was under the impression that smoking was banned in Bhutan, and that there were no pubs or discotheques. But the taxi driver, Karma Dorjee, said there was no such ban. “This king is great. He has given us the freedom of choice,” said Karma. In Thimphu, I saw several pubs and discotheques. “Young girls dance here for money. These dance bars are only for adults,” Karma said. Although smoking is banned, tourists and others were puffing away in public. And, public displays of affection are no longer taboo.

What seems forbidden is any discussion of the Doklam standoff in the trijunction of India, Bhutan and China. “Two big nations are fighting and we are caught in the crossfire. We don’t know where will we go if war breaks out,” said tour operator Sonaem Dorji.

So, no open support for India. Is support for China growing?

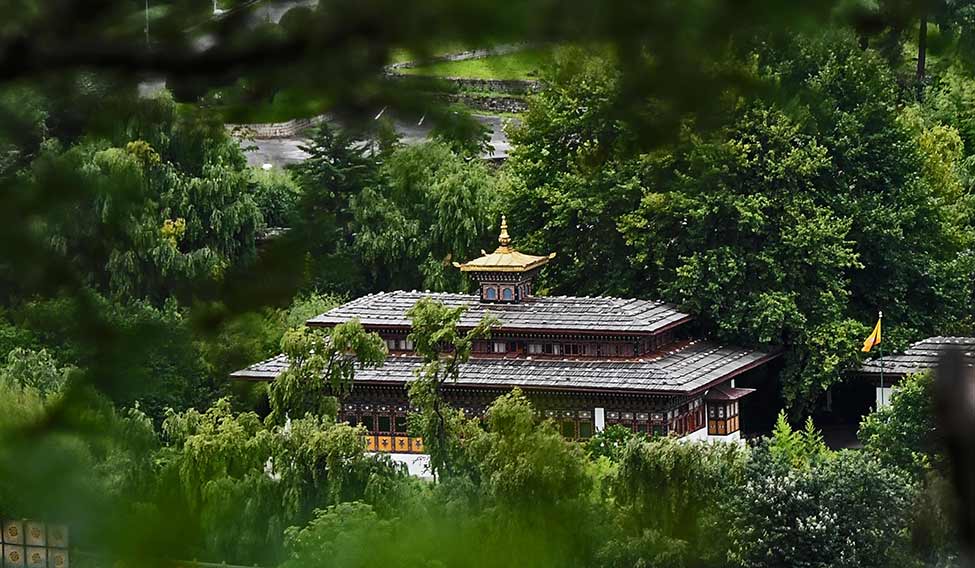

Majestic charm: One of the royal palaces in Thimphu. King Jigmey is said to be in touch with India to solve the differences caused by the Doklam crisis | Salil Bera

Majestic charm: One of the royal palaces in Thimphu. King Jigmey is said to be in touch with India to solve the differences caused by the Doklam crisis | Salil Bera

Sonaem said some Bhutanese supported China out of fear. “They will finish us if we get closer to them. China is a nasty country and we don’t want it to be here in any form. India controls Bhutan, but it will never invade us,” he said. As I spent more time in Bhutan, I realised that people like Sonaem could be in the minority.

For an official reaction to the Doklam crisis, I rang up the prime minister’s office and requested an appointment. Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay replied through his personal secretary: “For the next two months, I am totally occupied. I have a series of meetings and foreign trips.” The secretary directed me to the ministry of foreign affairs, with a word of caution. “If you raise the Doklam issue, you will not get any response. It is a calculated decision, which has come from the top. No one would speak a word,” he said.

Foreign Minister Lynopo Damcho Dorji’s secretary told me over the phone that the minister was in Nepal for a conference of BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation). “Neither the minister nor the officials would make any further comment on the Doklam standoff,” he said.

Located in northwest Bhutan, Doklam is an inaccessible piece of strategic real estate. The crisis erupted after China started building a paved road, which can carry vehicles up to 40 tonnes, in the region. It would have linked Bhutan with Tibet and threatened the vulnerable Siliguri corridor.

Strategic experts in Bhutan say that, to resolve the crisis, India should respect the Anglo-Chinese treaty (1890), which has been accepted by successive Indian governments since independence. “And that clearly says India would have access to Nathu La while China could access Doklam,” said political commentator and blogger Wangcha Sangey.

Bright moves: Artists rehearsing for mask dance, which is an integral part of Bhutanese culture | Salil Bera

Bright moves: Artists rehearsing for mask dance, which is an integral part of Bhutanese culture | Salil Bera

“It is highly immoral on the part of India to abrogate the treaty. Bhutan will not accept it. We may not raise our voice out of fear and pressure from India. But Doklam is an issue between China and Bhutan. India has no business to interfere in it,” Sangey told me.

It was probably the harshest possible view coming from anyone in Bhutan even as its government has opted to stay silent. Although the king himself is said to be in touch with India, Bhutan has only issued just a brief statement, “We want both India and China to settle their disputes as we do not want to see any war.”

A senior official in Thimphu told me that the Bhutanese government had requested India to withdraw its forces from Doklam so that China, too, would pull back its troops. India reportedly reduced the number of its forces, but there was no complete withdrawal. Subsequently, Bhutan refused to make any anti-China statements in India’s support.

To know more about Bhutan’s refusal to stand with India, I decided to meet Information Minister D.N. Dhungyel. Since it was Saturday, an official holiday, I went to his residence. The security staff let me in after I told them that I was from India and had come to schedule an appointment with the minister.

Dhungyel was not at home. He came back half an hour later and was surprised to see me. He was incensed when I told him that I wanted to discuss India-Bhutan relations. “How dare you come to my residence and talk on this subject?” asked the minister.

Love is in the air: King Jigmey Wangchuk kissing his wife, Jetsun Pema. The king’s public display of affection pleasantly surprised the entire nation | AP

Love is in the air: King Jigmey Wangchuk kissing his wife, Jetsun Pema. The king’s public display of affection pleasantly surprised the entire nation | AP

When I told him that the prime minister’s office had advised me to meet him, he wanted to know whether I had sought permission from the Bhutanese embassy in Delhi. It was clear that Dhungyel was afraid of discussing Doklam. “Two big nations are fighting and we are caught in the middle. Shouldn’t we feel scared? Definitely we are. We have decided not to utter a word over the issue. You may want us to talk, but we will not do so, never,” he said.

Before I could finish the tea that his daughter had served, the minister asked me to leave. As I started walking to the gate, dodging two dogs that chased me, I could hear the minister scolding his guards for letting me in.

As I got into the taxi, a guard stopped it and asked me to step outside. “The minister says he will sack us. We will lose our jobs because of you,” he said. I refused to get off, and one of the guards snatched my bag and searched it. He went through everything, including my notepad. When I protested, he told me to shut up. “This is not India,” he said. The guards threatened the taxi driver, Saran Subba. “They might arrest me,” said Saran. “We are not supposed to get this close to the high security zone.”

My next stop was the residence of Lyonpo Jigme Zangpo, the speaker of the Bhutanese National Assembly. In terms of stature and protocol, Zangpo is next only to the king. He, too, was not so happy to see me. “I am not here to answer your questions. How could you barge in here like this?” he asked. He said there was no damage to the India-Bhutan friendship. “But everybody would have to understand that national security is of utmost interest to us.”

Zangpo, however, revealed that Bhutan was talking to China about launching formal diplomatic relations. “I cannot tell you more,” he said. “Please understand that we maintain silence because of a well thought out decision taken at the top.” He said it was high time India embraced China.

Bhutanese government sources confirmed that the country, which once shared a special and exclusive relationship with India, was widening its diplomatic outreach. It now has diplomatic ties with 53 countries and is in the process of establishing ties with more.

The previous government under the DPT (Druk Phuensum Tshhogpa) party had established some links with the Chinese government. DPT leaders had met Chinese foreign ministry officials in Japan, South Korea and certain European countries. President of the DPT, Pema Gayamtsho, who is also the leader of the opposition, refused to comment. “As the government has decided not to make any remarks on the issue, I am refraining from making a statement,” he told me. Tshewang Rinzin, spokesperson for the DPT, said the Bhutanese government trusted India. “However, there are many people who raise doubts about ties with India, especially on social media platforms.”

Bhutan’s formal ties with India started in 1865 with the Treaty of Sinchula. Under the terms of the treaty, Bhutan ceded its territories in the Dooars region [which fall in present day Assam and West Bengal] to British India for an annual compensation of Rs 50,000. The treaty was amended in 1910 and it was in force till India became independent. A new treaty with similar terms was signed between Bhutan and India in 1949.

Political commentator Sangey said the treaty kept Bhutan completely isolated. “India guided our foreign policy for more than six decades. During all these years, Bhutan had diplomatic relations with only five or six countries. On top of it, India had included the word ‘protectorate’ in its policy towards Bhutan, something which the Bhutanese felt was disgraceful,” he said.

The situation changed only in 2007 after India, under prime minister Manmohan Singh, signed a new treaty with Bhutan. “As Bhutan now has the power to ascertain its friends, the people are understandably happy,” said Sangey. It is especially true for the younger generation.

At the clock tower near the Thimphu market, I met Santosh Rana, a young man with Nepali roots. Santosh, who did his engineering degree in Chennai, is looking for a job. He is planning to go to Japan as job opportunities are very few in Bhutan. He feels India is also facing a job market slump.

Santosh, 24, said it was important for Bhutan to have friendly ties with China. “Today, China is one of the major economies in the world. Even the US is afraid of it. Bhutan must have relations with China and it would gain a lot. Young people like us would benefit greatly out of that,” he said.

His classmate Thrinluy Namgyel, agreed with Santosh. “For years, we have been living in isolation. It is time for a change. We can have great relations with India even as we have relations with China,” said Thrinluy. Another friend, Sonam Wangchuk, who is also an engineering graduate from India, said China had always troubled Bhutan in the past. “If we establish close relations with China, it will make us another Tibet,” he said. Thrinluy, however, said China had changed a lot and an invasion was unlikely.

While young men are not afraid to voice their opinion, the academics are guarded, just like the administrators. “We don’t know about the repercussions if we open our mouths. If we say relations with China are the need of the hour, we cannot forget that we get maximum grants from India. Our trade is also mostly with India,” said a professor of international relations at the Royal Thimphu College.

Bhutanese government sources confirmed that China was becoming a key player in the country. The first major Chinese investment has come in the religious sector. Atop a hill in Thimphu, which is now known as Buddha Point, is a gold-plated bronze statue of the Buddha. The 169ft statue was installed to commemorate the 60th birthday of Jigme Singhey Wangchuk, the former king. The project, which cost nearly $100 million, was financed by Aerosun Corporation, a major equipment manufacturing company based in Nanjing, China.

Jigmey Thinley, a 27-year-old Buddhist monk, said so long as the Chinese did not interfere with their religious practices, the monks did not have a problem with them. He said the Bhutanese were open to more cooperation with monks from Tibet. Moreover, they did not accept the Dalai Lama as their religious leader as he had refused to listen to them. “He has never visited Bhutan. The Bhutanese probably might not accept his anti-China outbursts,” said Thinley. “Once when I was in Bodhgaya, I tried to get the Dalai Lama’s blessings. But he had a heavy security cover and I was denied entry thrice.” Thinley said he would never again try to meet the Dalai Lama.

Tapas Adhikary, an Indian telecom employee, has been visiting Bhutan twice every month for the past 15 years. He said the local people had become quite reserved towards Indians. “They no longer show any warmth, especially if you are not a tourist. And, the immigration officials do not even let us enter that frequently. Now they put a stamp on our passports as well,” said Adhikary, who is from Kolkata.

Ditching India, however, could prove to be a costly proposition for Bhutan. The Narendra Modi government has taken note of Thimphu’s shifting allegiance. Not a single minister or senior official visited Bhutan for talks after the Doklam crisis erupted. The only high-level contact happened on August 11 in Kathmandu where External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj spoke with Bhutanese Foreign Minister Damcho Dorji on the sidelines of the BIMSTEC summit.

Moreover, India is the most important donor for Bhutan’s development projects. For its 11th five-year plan, India has contributed Rs 4,500 crore. As ties deteriorate, India has suddenly slashed aid for hydroelectric projects in Bhutan from Rs 969 crore to Rs 160 crore.

On the trade front, the landlocked kingdom is completely dependent on India. Nearly 80 per cent of Bhutan’s imports come from India, and more than 90 per cent of its exports go to India. And, with India adopting the goods and services tax (GST), exports to India have become even costlier. “Our products will have to be competitive. But then we will also have to diversify. We need to look at other markets which have favourable tax regimes,” said Phub Tshering, secretary general of the Bhutan Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

Will that market be China? “Sorry, no comments,” he said.

Sonam Tenzing, director of Bhutan’s trade department, too, refused to confirm or rule out launching trade ties with China. “I don’t have the authority to speak on it. But it is being looked after at the highest level,” he said.

Trade with China is already common in north Bhutan, which borders Tibet. “People there cannot come to Thimphu or other towns as they have to seek permission. For us to go there, we have to take permission at the Indian Army base in Haa. So, they trade with Tibet, unofficially,” said a Bhutanese official.

Caught between two big powers, Bhutan is in a dilemma. But it may no longer be willing to take orders from India. Sangey said India was looking for a clear statement from Bhutan deploring China’s repeated threats of war on account of the Doklam crisis. “But India failed to convince Bhutan,” he said. “It is a big defeat for the Indian government. Bhutan has not fallen into the trap laid out by India.”