In 1875, Jamnabai, the maharani of Baroda, asked Gopalrao if he knew why he had been brought to the city. All of 12, Gopalrao said, “Why, to be made the maharaja, of course.” The answer urged Jamnabai, the sonless widow of Maharaja Khanderao Gaekwad, to adopt Gopalrao (from three aspirants) as her son and as the new ruler of Baroda. On May 27, 1875, Gopalrao, the son of Kashirao Dadasaheb (head of an extended family branch), became Sayajirao Gaekwad III, and went on to become one of the most revered rulers of Baroda.

The current king, Maharaja Samarjitsinh Gaekwad, 50, knows too well the legacy he has inherited. He became king in 2012 after the death of his father, Maharaja Ranjitsinh Gaekwad. “It took me a while to get used to being called maharaja,” he says. “But, I think it has more to do with the contribution of the family. The reverence continues.”

Almost every famous site in Vadodara has the Gaekwad stamp, be it the M.S. University of Baroda, the Senapati Bhavan, the Baroda Museum, the Ajwa reservoir, the Nyay Mandir (which houses the district court) or the Laxmi Vilas Palace. Sayajirao built the palace in the Indo-Saracenic Revival style in 1890. It is currently home to five members of the royal family—Samarjitsinh, his wife, Maharani Radhikaraje, their two children Padmajaraje, 11, and Narayaniraje, 9, and Rajmata Shubhanginiraje, Samarjitsinh’s mother.

A portion of the palace is open to the public, with a fee (ticket charges include a free audio guide), but photography is prohibited. Visitors have to commit to memory the breathtaking architecture, the skilled carvings on the pillars, the many jharokhas (a type of balcony) and the Raja Ravi Varma paintings that adorn the walls. There is also a palace shop that offers souvenirs.

The golf course surrounding the palace is a favourite haunt of Vadodara’s elite, while the palace grounds and the banquet hall often host wedding receptions. The gradual opening up of the palace was the brainchild of Samarjitsinh, who has a real estate business in Mumbai and is likely to start a commercial real estate venture in Vadodara. A sportsman himself, Samarjitsinh has revived the tennis and badminton courts, and has also set up many other sports-related amenities.

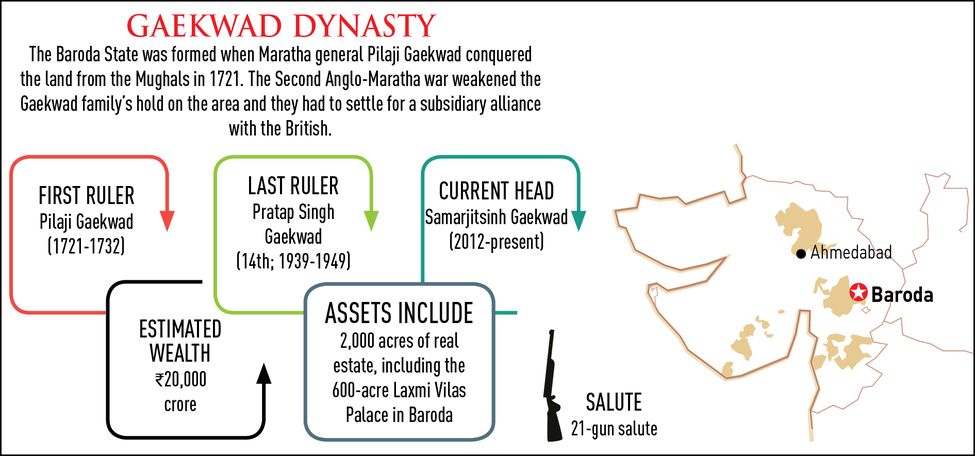

“The family did face tough times in the late 1990s,” he says. “It was a challenge to keep the estate self-sufficient. Tax laws were not friendly.” Samarjitsinh had two uncles—Lieutenant Colonel Fatehsinhrao P. Gaekwad and Sangramsinh Gaekwad. His father, Ranjitsinh, was second of three brothers. They also had five sisters. After the death of Fatehsinhrao in 1988, Ranjitsinh was made king. Sangramsinh went to court claiming his right to the property and, after 23 years of tedious proceedings, the dispute, involving Rs 20,000 crore, was settled about four years ago.

Samarjitsinh got the Laxmi Vilas Palace and more than 600 acres around it; Sangramsinh got the neighbouring Indumati Palace, the Nazarbaug Palace, most of the residential properties in Vadodara and Mumbai, and real estate owned by the family’s Alaukik Trading Company.

“I did not foresee such a situation (the legal case),” says Samarjitsinh. “It restricted me from developing my properties. I did not enjoy the time the court and lawyers took.” However, he bounced back and, if everything goes to plan, a portion of the palace will soon be converted into a heritage hotel. “It would have happened much earlier if the court case had not happened,” he says. “Many small things still have to be taken into consideration so that the originality of the architecture is not damaged.”

Castle class: Samarjitsinh Gaekwad inside the Laxmi Vilas Palace | Nafis Khan

Castle class: Samarjitsinh Gaekwad inside the Laxmi Vilas Palace | Nafis Khan

Samarjitsinh works from 9am to 6pm every day, reserving the remaining time for family. He ensures that he stays free when his daughters have holidays and he also, occasionally, drops them to school.

However, it is Radhikaraje who is with the girls night and day. “I also put them to bed,” she says. Fifteen years ago, Radhikaraje, from the royal family of Wankaner, Gujarat, entered the palace as a yuvarani. Now a maharani, with a masters degree in modern Indian history, Radhikaraje is overseeing the digitisation of the palace’s assets, which is expected to take four years.

Though she had heard about it, Radhikaraje had not seen the Laxmi Vilas palace before her wedding. “When the families were matchmaking, my family did not show me pictures of the palace or share a lot of details.” However, she did know the role the Gaekwads had in shaping Vadodara.

“Before the marriage, my mother had tutored me on a lot of things,” she says, with a smile. “I was told to touch my in-laws’ feet in the morning and at night. I was told not to wear an outfit without showing it to my mother-in-law first.”

However, she soon realised that the Rajput and Maratha cultures were quite different. “The Maratha culture is a bit relaxed,” she says. “My father-in-law used to tell me to never get up when they entered the room, especially when I was eating.” A day after her wedding, she showed her mother-in-law the sari she wanted to wear. “She just told me not to do that and wear whatever I was comfortable in,” says Radhikaraje. She says she was awed by her in-laws’ humility.

And, it is this humility that Samarjitsinh wants to instil in his children. He wants to expose them to the world while giving them a strong, rooted upbringing. The royal couple loves to travel and, some time ago, they had taken the children camping and hiking in Bhutan. “To celebrate my 50th birthday, we [the couple] drove down from Serbia, Bosnia and Croatia,” he says.

As with most royals, Samarjitsinh, too, has a connection to cricket—he is president of the Baroda Cricket Association. In fact, the love for the game runs in the family. Mamasaheb Ghorpade, who played eight Tests for India, was his father’s uncle. His uncle Fatehsinhrao was the manager of the Indian teams that toured England and Pakistan in late 1950s and 1970s.

Samarjitsinh played Ranji cricket for Baroda and also represented the West Zone. “I batted in the top three,” he says. He loves Test cricket and once went to Lord’s to watch an India-England match. “I would love to go to Australia to see a Test,” he says.

Like cricket, politics also runs in the family. Samarjitsinh’s father, who was also an established painter and singer, and uncle Fatehsinhrao represented the Congress in Parliament. But, later, the family’s allegiance shifted to the BJP. In the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, Rajmata Shubhanginiraje contested and lost as a BJP candidate from Kheda. Though Samarjitsinh is also associated with the BJP, he is not active in politics, at least for now. Every election, however, there are rumours that a royal might get a ticket. “There is a lot that can be done by joining politics, but there is a lot that can be done without joining politics,” he says. “The sheer population of the country is a challenge. Aspirations have grown and politicians are playing to these aspirations. They indulge in quick fixes and that is scary. Cities have now lost their identities. The city should be able to decide on its planning and the authorities should be open to suggestions.”

If he does contest, the family’s reputation might help his cause. Bansidhar Sharma, coordinator of Shree Sayaji Foundation set up by the MSU, says he is awed by the contributions of the Gaekwads. Back in 1906-07, Sayajirao Gaekwad III made education free and compulsory for all; even the British parliament took note of it, he says. Sayajirao III also played an important role in national awakening, he says. “We are now talking of sab ka saath, sab ka vikas (together with all, development for all), but sarva dharma sambhav (religious harmony) was practised then,” says Sharma.