It didn't go well. Half an hour after the April 26 meeting between the foreign secretaries of India and Pakistan in New Delhi, it was clear that the talks were headed nowhere. The Pakistan high commission's statement about the meeting had references to Baluchistan and Indian spies and mentioned the need for the two countries to engage further. There was nothing in it that India wanted to hear. It was a dead end.

It has not been an easy week for South Block as India’s difficult neighbours dominated the news cycle with their versions of events. Issuing an Indian visa to Uighur activist Dolkun Isa and subsequently revoking it under pressure was a ham handed way of dealing with China. The tough stand was probably in response to the Chinese opposition in the United Nations to declaring Jaish-e-Mohammad leader Masood Azhar a terrorist. And, the climb down was a major loss of face for India. The failed meeting between the foreign secretaries came soon after. It did not help that External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj was hospitalised with pneumonia.

“The statements speak for themselves,’’ says former diplomat Vivek Katju about the failed talks with Pakistan. “They bring up Samjhauta [train blast case], but in our statement it is absent. There is Mumbai in ours, but there is no mention of it in Pakistan’s statement. They bring up Kashmir, ours statement doesn’t have it. And the way we both look at the Kulbhushan Jadhav incident [the Baluchistan spy case] is completely different.”

It looks straight out of Akira Kurosawa’s iconic film Rashomon, in which characters narrate the same incident differently. In the heat of April, the Indo-Pak relationship seems to have wilted. As former foreign secretary Lalit Mansingh says, no prime minister has ever been able to tackle the challenges faced by the Indian diplomatic cadre on China and Pakistan. “Yet, you learn from experience, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi hasn’t really shown any clarity on whether these lessons have been learnt,’’ he says. But it is difficult to fault Modi alone. As far as Pakistan is concerned, there are only two choices in the box—bad decisions and worse ones, says a former high commissioner to Pakistan.

Modi stormed in on the promise of a new era. His well-attended swearing-in ceremony set the tone and then there was the hug in Lahore on Christmas day when Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was celebrating his granddaughter's wedding. But as one seasoned diplomat puts it, every Indian prime minister has a fatal flaw. It is the belief that he or she will be the one to bring peace between India and Pakistan. Modi is no different, but in his attempts to bring about rapprochement, policy flip-flops have become more pronounced and frequent.

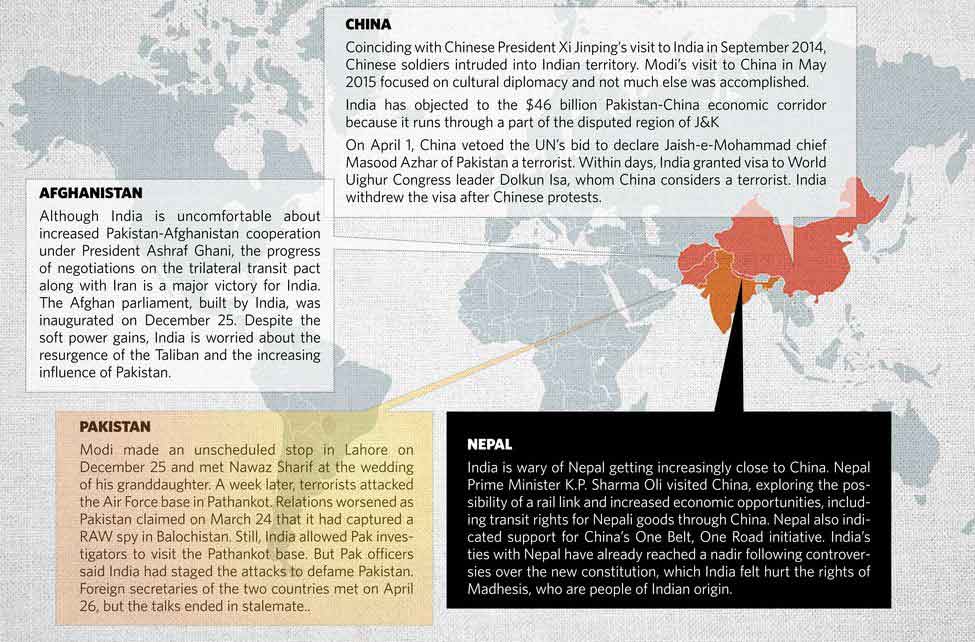

Bilateral talks have been on and off, repeatedly. The bonhomie of the swearing-in quickly wore off, with India cancelling bilateral talks over the Pakistan high commissioner meeting separatist leaders. After a series of highs and lows, the secret meeting of the national security advisers held last December in Bangkok set a positive tone, leading to Swaraj's visit to Pakistan for the Heart of Asia conference. It set stage for Modi's surprise visit to Lahore on Christmas day and the scheduling of foreign secretary level talks for January 15. But terrorist attacks on the Pathankot Air Force base, which happened barely a week later, upset all plans, delaying the talks for more than three months.

One of the major challenges Modi faces is the absence of domestic support. The general lack of consensus seems to have spilled into the realm of external affairs as well. “The differences have now broken into the foreign policy arena, where earlier there was a consensus. Even in the Vajpayee era, there was much more open diplomacy,’’ says Mansingh.

As Pakistan turns hawkish, largely because of domestic compulsions such as civil-military tensions, the way forward may not be easy for Modi. But as he has stuck his neck out on the issue with his visit to Lahore, keeping Pakistan engaged is crucial for him. But there seems no tangible way forward. “There is a need for political consensus on how to deal with Pakistan. Also we need an effective, calibrated strategy,” says C. Uday Bhaskar, director, Society for Policy Studies, a Delhi-based think tank.

With Modi’s penchant for keeping things close to his chest, Pakistan has been able to create an impression that it is India which is dragging its feet. Moreover, under Modi, external affairs is run out of the PMO, overseen by National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and Foreign Secretary S. Jaishankar. Although exceptionally brilliant and hardworking, both are not known to be team players. “Doval is a counterinsurgency specialist. And, he is overburdened with other stuff, including planning the PM’s political trips,’’ says a former spy.

So, does Modi really have a strategy to handle China and Pakistan? “There are glimmers of bold thinking, but no stamina to push those through,’’ says Mansingh. But this seems to be how the Modi magic works. Lots of vigour, plenty of excitement, and as Bruce Jones, director of foreign policy programme at Brookings Institution, says, “great power speed dating.” India has gained many new friends. But the real test lies in turning the dating into a committed relationship. It is here that Modi falls short. Despite the progress made in ties with a number of countries ranging from Mongolia to Saudi Arabia, there is an inability to push tough ideas through.

The Dolkun Isa issue is a case in point. India took a courageous decision to issue Isa the visa to attend a conference to be held in Dharamshala despite him being notified by China as a terrorist. He got an e-visa in 20 hours, although it normally takes up to three days. It was touted as India's tough response to the Chinese decision to save Mazood Azhar from being declared a terrorist by the UN despite direct personal entreaties by Doval, Swaraj and Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar. A few days later, however, the visa was revoked, following noisy protests by China.

“It was embarrassing,” says Jayadeva Ranade, former member of the national security advisory board. Rakesh Sood, former ambassador to Afghanistan, says the move smacks of incompetence. “It is flying by the seat of your pants. There seems to be no reasoned decision making or discussion. You are dealing with the issue of the day. It is firefighting. It does not lead to policy,” he says.

Uncertain future: Sushma Swaraj with Pakistan foreign minister's adviser Sartaj Aziz in Islamabad last December. Efforts to normalise ties with Pakistan have always been hit by roadblocks | AFP

Uncertain future: Sushma Swaraj with Pakistan foreign minister's adviser Sartaj Aziz in Islamabad last December. Efforts to normalise ties with Pakistan have always been hit by roadblocks | AFP

India's China policy, despite the selfie moments he created, has always been uneasy. The lesson that China needs to be dealt with in a firm manner and that it will not be moved by Modi’s charm offensive was clear from the visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2014. There was a Chinese border incursion to coincide with the visit and it went on despite the hospitality that was on display, with Modi flying down to Ahmedabad to receive Xi, breaking protocol. The return visit was lost in cultural diplomacy and yoga. “We haven’t learnt to talk to the Chinese in the language they understand. The whole thing was a flop,’’ says Mansingh, who thought the decision to grant visa to Isa was part of a new thinking. “But before I could celebrate, we withdrew the visa. It was a bold initiative that quickly turned into a retreat,” he says.

For Modi, who came to power promising a tough line and shares a chemistry with Xi, the inability to make the dragon crouch actually raises the question, like in the immortal song of the Bee Gees, How deep is your love. It is believed that Modi tried to raise the border issue with Xi during his visit to Xian, but he was snubbed by the Chinese president. Xi apparently turned to the official next to him and asked, “Why is he bringing this up here?’’ Modi was told that such discussions would take place in Beijing. But nothing happened in Beijing. As usual, the Chinese controlled the narrative. India's relations with Pakistan seem to be progressing on a similar trajectory.

“Even if it was a mistake, no one will believe it,’’ says Ranade about the visa issue. “You embarrass yourself and then trot out excuses. It, in fact, gives an opening to point out that we issue visas without verification. This is not the first time that China has voted against us. There was Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi, too. The Chinese are in bed with Pakistan that they can’t afford to annoy them.”

India has given concessions like e-visa to the Chinese without getting anything in return. The home ministry was not in favour of granting e-visas, but Modi chose to please China. Indian concerns over Chinese investment in Pakistan and the proposed economic corridor have fallen on deaf ears. The hot line that was supposed to be set up between the military headquarters is still not functional. Even the Sino-Indian land boundary agreement is not making any forward movement. It didn’t help that Doval, who is also the special envoy for border talks with China, chose to cancel a meeting with his counterpart because of the Pathankot attacks. And, with China and India competing within the same sphere of influence, the tension is only likely to grow.

The deepening China-Pakistan ties, especially through the proposed economic corridor, are likely to exacerbate tensions with India further. Even though India showed an appreciation for Chinese concerns by revoking the visa issued to Isa, China does not seem to have a similar view on the Azhar issue. All China had to say was that it was “the responsibility of all countries to bring him [Isa] to justice’’. The situation gets even more complicated with growing India-US ties, especially in the defence sector.

Not everyone, however, believes that India has mishandled the Isa imbroglio. There is a view that the move by India to grant visa to the Uighur leader and then cancel it should be seen as a warning to China. “It shows China that India could use this in future,” says a diplomat from southeast Asia. “After all, if India had let in a terrorist, even if it was only in name, it would have lost its moral standing.”

Srikanth Kondapalli, professor of Chinese studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, says there was some tough talking by both sides during the visits of Doval, Swaraj and Parrikar. “We put them on notice. The volte-face is probably because of pressure by the Chinese,” he says. “But had we let Isa in, we would be equating China with a terrorist state. It would have cost us.” Kondapalli says at the next UN meeting, China would perhaps take a different view on the subject of Azhar. “The public climb down will have its benefits.”

While this might be “wishful thinking” as strategic affairs analyst Sushant Sareen puts it or “baloney’’, as Uday Bhaskar sees it, India’s difficult neighbours will not be easy to placate, especially as India tries to become more ambitious and turn into a bigger player in the region. The question is, will Modi be able to move from speeddating to committed relationships?