Domru Kilo lives in a shack at Ramguda village in Odisha’s Malkangiri district, which borders Chhattisgarh to the north and Andhra Pradesh to the south. In his early thirties, Domru has never been a beneficiary of any government scheme, nor have politicians come to his village seeking his vote. In fact, he grew up without knowing much about what lay beyond the lush green mountains and the Balimela reservoir that border Ramguda.

His seemingly idyllic village, however, is part of the Dandakaranya muktanchal, the “free zone” of the Communist Party of India (Maoist). With their firearms and other, cruder, weapons, the Maoists rule by diktat here. Their grip over the region is so firm that Domru had never seen a policeman enter his village, not until the horror on the midnight of October 23 and 24.

That night, about 100 metres from Domru’s house, top leaders of the CPI (Maoist) were holding a meeting. Farther away were their gunmen, preparing dinner for the group. Out of nowhere came two helicopters, which began firing down on them. The Maoists were taken by surprise, and trapped. On ground, they were surrounded by the elite Greyhounds of Andhra Pradesh and the Special Operation Group of Odisha. “Bullets flew, and two choppers landed on the banks of the reservoir,” recalled Domru. “More than two dozen security personnel got down and surrounded the village.”

Witnesses said there were around 40 security personnel on the ground and about 50 on the choppers. “But the men of our party (Maoists) outnumbered the security forces,” said Domru. “Many leaders managed to escape. But I had never seen so many deaths in our area before this attack.”

More than 30 leaders and commanders of the CPI (Maoist), including seven members of its women squad, were killed in the attack. Security forces estimate that nearly 150 Maoists had assembled in the village.

After the firing on the Maoists, said Domru, the forces went door to door, firing on the houses and asking villagers to hand over Maoists. He pointed at the wall of his hut; part of it was destroyed by bullets. He said his one-year-old nephew, who had been inside sleeping with his mother when the security personnel came, was lucky to be still alive.

“[One of the security personnel] held me by the collar of my shirt and asked me to show him the spot where the senior leaders were hiding,” said Domru. “They promised me to pay for the information. When I pleaded and told them that we did not need the money, they warned us that, one day, we would have to pay a heavy price for supporting our party.”

An hour after the operation began, the choppers flew away with the bodies of slain Maoists, leaving behind charred remains of utensils, food grains and vegetables. There were even bottles of perfumes and beauty creams for ladies, suggesting the quality of the lives Maoists lead in the forest.

The attack has not just put the Maoists on the alert, but also made the lives of villagers in the region even more difficult. A month and a half after the operation, an inquiry carried out by the janatana sarkar (the people’s government of the Maoists) found that the security forces had acted on information provided by Kantama Sisa, a 40-year-old woman in Ramguda. Apparently, it was through Kantama that the police learned that top Maoist leaders such as Rama Krishnan alias RK, Gajarla Ravi alias Ganesh, and Chalapathy would be attending the meeting in the village on October 23.

The punishment was swift: Kantama was executed in public on the night of December 12. Only a handful of villagers were brave enough to take her body to the banks of the reservoir and light the pyre. And even they went back before the fire went out.

When THE WEEK visited Ramguda a few days later, Kantama’s body lay half-burnt, and we could see wild animals lying in wait some distance away. Domru looked at the body and said he would meet the same fate if he took the side of the security forces. “This is the situation in village,” he said. “They hit our sarkar here, but they could not damage it permanently. Today, there is no security personnel in sight, but our party has come back with full strength.”

Living hell: A woman at work in her home at Ramguda. With the Maoists on the alert, the lives of villagers have become even more difficult | Salil Bera

Living hell: A woman at work in her home at Ramguda. With the Maoists on the alert, the lives of villagers have become even more difficult | Salil Bera

Domru said living under the Maoists was not unpleasant, as they gave villagers the right to land and forest. Yes, there was no democracy, he conceded. “But what do you people get for voting for your government?” he asked.

Another villager, Mongla Kilo, said: “They give us drinkable water. They ask us to raise our voices against the Indian government for neglecting us. We pay them a part of our hard-earned money. If we fall sick, they pay us back. If we are short of food, they give us food. No one here dies of starvation. During droughts, they give us money to take care of our farmland. Our party does so many things for us that the government could never do.”

But, despite Mongla’s claims of farmers receiving incentives, THE WEEK saw little sign of agricultural activity in the Dandakaranya zone. What was interesting was that cannabis and poppy were being cultivated across hundreds of acres. When asked about it, Domru said, “I don’t know. Villagers planted them at night.”

As we made our way through villages, we saw many women watering and spraying pesticides on the plantations. Apparently, cannabis and poppy are major sources of income for the “government in the forest”.

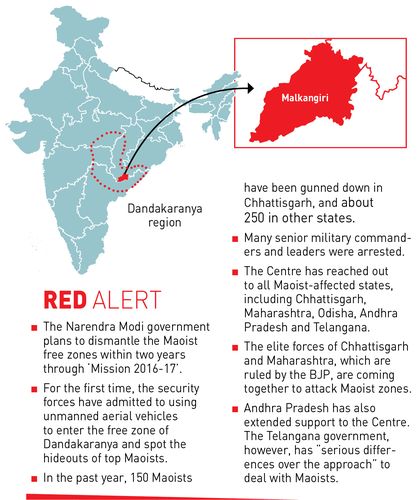

But, with the security forces stepping up their offensive, the Maoists seem to be in retreat. Security officials told THE WEEK that the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance government is so determined to eliminate the Maoist threat that, in a first, it has given the greenlight for carrying out aerial strikes wherever necessary. Apparently, the Centre’s decision to liberate the “free zone” in a year or two was taken after consulting states affected by Maoist violence, such as Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The operation has been named Mission 2016-2017, and it involves security forces going deep into Dandakaranya and destroying Maoist camps.

Apparently, not all state governments approve of the Centre’s grand plan, but none has lodged any protest. Sources say states like Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra, which are ruled by the BJP, have joined hands to fight the Maoists. Their special forces are working together. Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu, whose party is a constituent of the NDA, has also extended his support to the mission. The Telangana government, on the other hand, has made clear its “serious differences”.

The Centre’s plan was reportedly formulated a year after Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office. In 2015, Modi set up a special cell to work on a strategy to finish off the Maoist threat. Later in the year, National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, along with K. Vijay Kumar, special adviser to the prime minister on anti-Naxal operations, and directors-general of paramilitary forces, started visiting the Dandakaranya zone and Nagpur and Gadchiroli in Maharashtra to assess the ground situation. In their meetings, it was decided that aerial surveillance and retaliatory attacks would become part of anti-Maoist operations.

According to sources, in a meeting held in Raipur in Chhattisgarh in October 2015, officials who were part of Modi’s special cell asked the Special Task Force of Chhattisgarh, Greyhounds of Andhra Pradesh, Cobra (Commando Battalion for Resolute Action) of the Central Reserve Police Force and Garud commandos of the Air Force to start practice drills on helicopters in Bijapur district in Karnataka.

Asked about this, D.M. Awasthi, special director-general in charge of anti-Naxal operations in Chhattisgarh, said carrying out air strikes was part of the larger plan to crack down on Maoists. But he maintained that the government had not taken any specific decision regarding such strikes, and that they were being carried out as a retaliatory measure.

“Yes, we will not hide the fact that it is being used,” Awasthi told THE WEEK. “With every operation team being sent deep into the forest, we are sending Garud forces on aircraft. If we have to finish the insurgency, we need choppers. If our forces are threatened, we conduct aerial strike to retaliate. How could we accept the loss of lives of security personnel? We have to hit them with minimum casualty on our side. We cannot let our forces die while conducting operations. So, at times, the choppers are necessary. But we are sure that we are not misusing it.”

Rights activists, however, are not convinced. “How could they say this? Will the aerial strikes be controlled by the headquarters?” asked C. Chandrasekhar, general secretary of Committee for Civil Liberties in Andhra Pradesh.

Awasthi said the change of strategy in 2015 aided the forces to claim victories in 2016. “Trust me, we have entered areas we had never been able to penetrate since Naxalites declared their free zone,” he said.

He revealed that Modi and Chhattisgarh Chief Minister Raman Singh were together monitoring the progress of the mission. “Both the Central and state governments have asked the security forces to fix a target and timeframe to eliminate the Naxalites in this zone [Dandakaranya],” he said.

Asked what the timeframe would be, Awasthi said, “It is impossible to say, as Maoists have spread to different states. But this time, all the states have joined hands to eradicate the insurgents, which is a positive thing.”

According to senior police officials in states where Maoists are present, Modi met directors-general and operation chiefs of various security agencies at a national convention at Baloj in Gujarat in December 2015. “In the meeting, he asked the officers to give fruitful results in the crackdown on Maoists, not the usual, ineffective measures,” said an officer. “He asked the security personnel to hit the Maoists in their free zones. For that, he said, the Central government was ready to spend money.”

Kalyan Rao, poet and civil rights activist, said the government’s desperation had an economic reason. “The present prime minister wants multinationals to access bauxite and other mineral deposits in Dandakaranya,” he said. “That is why he has designed such a drastic policy to finish off the Maoists.”

Black harvest: Cannabis and poppy are cultivated across hundreds of acres in Dandakaranya | Salil Bera

Black harvest: Cannabis and poppy are cultivated across hundreds of acres in Dandakaranya | Salil Bera

Maoist-dominated areas in several states have attracted investment proposals worth around Rs 3 lakh crore. The majority of the proposed investments from big corporate houses are in mining, steel and power sectors, and require state governments to acquire three lakh acres. Of 45 mines in the Dandakaranya zone and Gadchiroli district in Maharashtra, 30 are now under the control of private companies. On December 23, Maoists torched 69 trucks in Gadchiroli, stepping up its campaign against mining in the district.

The government’s plan, which it began implementing last January, has already claimed the lives of around 250 Maoists across India—150 of them in Chhattisgarh alone. Many leaders of the CPI (Maoist) and senior commanders of the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army, its military arm, have either been arrested or killed. For the first time in the past 30 years, the security forces have Dandakaranya under the surveillance with the help of unmanned aerial vehicles.

For the Maoists, the crisis is so deep that they have announced that they would no longer be doing guerrilla warfare and would only retaliate when attacked. “This [2016] is the best year in the history of anti-Maoist operations,” said Awasthi. “The Naxalites are badly beaten and are suffering.”

It is a far cry from the situation six years ago, when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government was in power and P. Chidambaram was Union home minister. Operation Green Hunt was on, and the security forces in several states wanted controlled air strikes on the Maoists. But the government had to turn down the demand because of tremendous political pressure.

Now, though, such strikes are being carried out carefully and covertly. Asked about air strikes, N. Surendra Babu, chief of Greyhounds of Andhra Pradesh, told THE WEEK: “Greyhounds, as a policy, does not make any comment to the press.” He directed us to N. Sambasiva Rao, director-general of police in Andhra Pradesh. “The DG would not like to make any comment on air strikes,” Suresh Babu, Rao’s press secretary, told THE WEEK.

According to Special Operation Group of Odisha, the encounter in Malkangiri in October was the first time that the Maoists had suffered a huge setback. But, when asked about air strikes, R.P. Koche, inspector-general of operations, said, “We cannot share the details of how we carried out the strikes against Maoists and how we will be doing that in the future. It is part of our strategy.”

Apart from the states that have the BJP or its allies in power, only Odisha has supported Mission 2016-2017. The police in Telangana, however, have refused to cooperate with it. Anurag Sharma, director-general of police in the state, told THE WEEK: “Not at any point of time would the Telangana Police use air strikes against Maoists. It is the policy of our government.”

Sharma said the police in Telangana had not taken part in the recent operations in Malkangiri or anywhere else, even though the majority of Maoist-affected districts of undivided Andhra Pradesh are now part of Telangana. “All major strikes in the recent months were carried out by the police in Andhra Pradesh,” he said.

Documents of the Dandakaranya zonal committee of the CPI (Maoist) that are in possession of THE WEEK mention helicopters hovering over the zone. “The Maoist government is threatened by the police,” says one document. “Garud commandos of the Indian Air Force are ready to make air strikes…. Dandakaranya is blazing in the flames of the cruel repression unleashed by the Central and state governments.”

According to Maoists, the Garud commandos and the special task forces of various states are ruining the peace and property of villagers in the free zone. They said the security forces were attacking schools run by the party, killing its teachers and raping women at night. “If villagers retaliate, shells rain down from the sky,” says a document.

The documents confirm, for the first time, that there is a parallel government in place in Dandakaranya. The area is divided into different zones that have their own janatana sarkar. All such local governing bodies are monitored by the central committee, known to be the top decision-making body of the party.

What the security forces have been doing in recent times is to try and identify leaders of each zone and eliminate them. Every area under the control of the Maoists has a chief, who is called the president of the government of that area. This year alone, the attacks have killed about 50 such chiefs and members of local Maoist governing bodies.

Maoists are also known to run a large number of schools, the objective of which, according to security officials, is to brainwash children into taking up arms when they grow up. The forces have either killed or arrested many teachers in such schools in Dandakaranya in recent times.

Maoists themselves have conceded that the government was crushing their local governing bodies. “Without any provocation, the Indian government is destroying our government by killing our leaders one by one,” said a Maoist document released just after the Malkangiri encounter.

One such Maoist leader killed was Kursham Dharmana, president of the Singaram area in Telangana. He and Vatre Rajal, another member of the Maoist local government, were captured last July from Sukma in Chhattisgarh. “They were taken to Gollapalli police station [in Andhra Pradesh], tortured and then killed,” says a report of the Dandakaranya zonal committee.

Maoists allege that the forces who took part in the July attack fired indiscriminately at civilians. “Along with our leaders, many innocent villagers were killed,” says the report. “Even a group of tribal artists and teachers of schools run by us got killed.”

Hemula Podiyal, a tribal theatre artist, allegedly died on the spot when security forces threw a grenade and set his room ablaze on July 29. The houses of 19 other artists were also attacked. “Some of them managed to flee,” said the report. “Around four artists were burnt to death along with Hemula.”

The propaganda bureau of the Maoists concedes that the security forces have been able to enter hitherto impenetrable areas of Dandakaranya. It also says the government of India has been able to “create confusion” in the minds of the people in the free zone. “The government says they have hit us so badly that we would not be able to stand up. This is exaggeration. Yes, we have been threatened, but we have not lost,” said a statement from the bureau.

According to the Dandakaranya zonal committee, the Indian government is trying to hide its human rights violations to sell its success story. “The police and paramilitary groups are meant to kill innocents and rape young tribal women,” it said.

Some Maoist documents cite specific and serious allegations. One is the killing of a couple who dropped out of the party three years ago. The security forces allegedly gang-raped the woman. “Hakpa Manor and Thathi Pande… left the [Maoist] government in 2013, and were living an ordinary life. The police picked them up from Karnar village in Bijapur on May 17, 2016, and tortured them severely. Pande was mass-raped. After they were murdered on May 21, it was announced that two Maoists had died in an encounter,” says a document.

Domru Kilo, resident of Ramguda

Domru Kilo, resident of Ramguda

Awasthi admitted that he had received a number of complaints from villagers regarding fake encounters and crimes against women. “I can assure you that every complaint would go through magisterial inquiry and impartial investigation,” he said. “If any of the complaints is proven right, we would take stern action.”

It was in an attempt to know how the Maoists were faring that THE WEEK ventured into Malkangiri in December, a few days after Kantama was executed. Fifty kilometres before Malkangiri town, the road ceases to exist. In some parts, the Maoists had changed the course of the river to destroy the road. Our driver gave up and said, “Only an old four-wheel-drive jeep could go into the forest.”

Around five hours of journey from the nearest town in Andhra Pradesh led us to a village on the Odisha border. The village, it seemed, was the last outpost of the world’s biggest democracy. It was 9am, and an intimation was sent to the forest for entry to the free zone. Soon, young people on motorcycles arrived and asked, “Why are you here?”

The Indian government has imposed restrictions on visiting Malkangiri. One has to apply beforehand, stating the purpose of one’s visit, to enter the prohibited area. Rights organisations were permitted to enter Malkangiri after the encounter in October, but that was only to visit villagers at a particular area. Apart from them, no one is allowed to go, as the government does not want any untoward incident involving outsiders.

It was braving such restrictions that we undertook the journey. After receiving the go-ahead from the Maoists, we travelled 12 kilometres on a tractor deep into the forest. As we made our way, the branches that hung low grazed our faces and bodies. We held on to our seats even as our hands became numb in the cold of the winter.

The tractor jerked along, through potholes that were several feet deep. After a nerve-racking three hours, we reached a point from where even the tractors could not go on.

A two-hour-long trek lay ahead of us. We first crossed a river and then made our way up and down the hills. The tiring journey ended at Ramguda, where the choppers had carried out the strike in October. The village, despite being surrounded by forest, looked oddly habitable. “The jungle here looks horrible and animal-infested,” said Surangi Kole, a villager. “In reality, though, it is very much liveable. There are no animals because our leaders stay and rule from here.”

The villagers said they felt safe living there. Yes, there were no government schools, but they were allowed to send their children away to study. “But those who go outside are first trained to distrust the government and its machinery,” said Sirsa Kole, a 50-year-old. “Our boys receive their preliminary education from the party and its government.”

Ramguda and nearby areas have electricity supplied by a private power company based in Malkangiri. When they fall sick, doctors are made available within a short while. All these conveniences, however, come at the cost of their freedom. Every time the villagers go outside, they have to brief the Maoists about the people they meet, or plan to meet, outside the village. Being economical with the truth leads to what Kantama had to face.

Moment of triumph: Security personnel displaying the arms, ammunition and clothes seized from the Maoists after an encounter in Latehar district in Jharkhand in December | PTI

Moment of triumph: Security personnel displaying the arms, ammunition and clothes seized from the Maoists after an encounter in Latehar district in Jharkhand in December | PTI

Despite the effort we made to reach Ramguda, the villagers were reluctant to allow us to meet the Maoist leadership. It was only when night began to fall, soon after we began our journey out of the Maoist zone, that a 50-member team in black uniform appeared in front of our tractor.

All of them were carrying Kalashnikov rifles. The team was led by Gajarla Ravi alias Ganesh, the chief of the Dandakaranya zone and central committee member of the CPI (Maoist). It had around 20 women, and they were patrolling the village to see the deployment of squads in Malkangiri. None of them seemed nervous, or sad at losing their comrades in the encounter in October. “We have recovered,” said Sunitha, a commander who hailed from Warangal in Telangana. “We are ready to tackle any situation now.”

An older commander nodded his head approvingly and said, “In the past, we had difficulties finding women members in our squad. But it is easy for us now, as the government is helping us by being aggressive against women in our areas. Our rule in Dandakarnya is intact.”

Besides flashlights and sophisticated rifles, all the team members had walkie-talkies in their hands, apparently Chinese made. Tied around their waists and shoulders were ammunition packs.

What was more interesting was that several young boys, some just out of college, were part of the team. One of them, aged 21, left his college in Bastar in Chhattisgarh to join the CPI (Maoist) soon after the Malkangiri encounter. Asked about what prompted him to do so, he replied: “I have many reasons. Yes, I joined after my brother, a Maoist, was shot down by the police. But the biggest reason I joined the struggle was the sexual violence meted out to young women of my village who sympathised with our party. And whatever the Modi government might do, our revolution will continue.”

In the silence of the night, the boy’s words rang loud and clear. At that moment, we realised that, with or without air strikes, it would take many more encounters for the security forces to finish off the Maoists and their deep-rooted ideology.