It is no coincidence that ‘notebandi’, the demonetisation of high-value notes by the Narendra Modi government, sounds a lot like ‘nasbandi’, the infamous sterilisation drive during the Emergency under Indira Gandhi. With long queues outside ATMs that seemed perpetually dry, the country has almost been cashless since Modi announced the demonetisation of 500- and 1,000-rupee notes on November 8. Curiously, that timed perfectly with his campaign for a cashless India or, as he twisted it, a less-cash India.

As cashless economy became the main focus, the talk of black money and counterfeit currency took a second place in the government’s scheme of things. The benefits to the economy and people of buying, borrowing, paying and selling without currency notes became the discourse from South Block, the Reserve Bank and the NITI Aayog. Indians, who had almost entirely been dependent on cash, were hurtled into a digital financial future, and most of them were caught unprepared.

Indians in cities have been using credit and debit cards, net banking, and even e-wallets to shop online, book train and flight tickets, make hotel reservations and pay the cabby, and even the maid and driver. It is those in Bharat, who are feeling let down, as in many cases their livelihood is threatened. “Modiji ne kaha ki amiron ko, paise walon ko line mein khada kar diya..lekin hum hi line mein khade hai,aur paisa hai hi nahi. (Modiji said he has made the rich stand in line, but it is we who are in the line, and there is no money.) One hears it very often in rural India.

Modi, indeed, said that. It was intended to get audience cheer him at a rally where he commended the way people were supporting him despite facing difficulties because of demonetisation. The villagers, however, seemed concerned more about reality rather than heroism—no money in their hands for any of their needs. And they started calling it ‘notebandi’.

In fact, the government has been headed towards a cashless economy for quite a while, with the Reserve Bank creating a technology-driven payment and settlement ecosystem. Staying the course with Aadhaar cards, then opening Jan Dhan accounts and initiating a series of steps around the mobile phone were aimed at moving from cash to less cash. Promoting mobile and digital banking to spur financial inclusion has been a vision of the government’s Digital India programme.

A study by the payment technologies company Visa, which was submitted to the NITI Aayog just before the demonetisation, said using cash was costly for the country. It cost 1.7 per cent of India’s real gross domestic product in 2014-15, said the study. Another study, done in 2014 by the Institute for Business in the Global Context, part of The Fletcher School at Tufts University in the US, pointed out that most Indians lacked the means to do non-cash payments even if they wanted to.

The study said people mostly used cards to withdraw cash from ATMs rather than making cashless payments. Though there is a fiercely competitive telecommunication sector in India, fewer than 2 per cent of mobile phone users had used a mobile phone to make a payment. Aadhaar, said the study, would reduce costs of serving India’s unbanked population. It made another interesting point—though people did not pay anything to transact with cash, as they did with cards, they spent time on fetching cash. “Delhi’s 11 million inhabitants collectively spend some 6 million hours per month fetching cash; Hyderabad’s 6.8 million spend 1.8 million hours,” it said.

These and many more reasons were adduced to say one thing—it is high time India moved to a less cash economy. But does that justify a demonetisation announcement with a four-hour notice?

“Demonetisation has hit the agricultural sector worse than a third continuous drought could have,” said food policy analyst Devinder Sharma. “More than 70 per cent of India has been hit where it hurts the most. In the cities, people will only have to stand in queues to get their money; in the countryside, there is no income for farmers who toiled for six months and were hoping for revival of livelihoods given the good monsoon.”

Wholesale prices of most of the major crops, vegetables and flowers had slumped, he said. Tomato growers in Chhattisgarh were offered 25 paise for a kilo for their crop and potato growers in Himachal Pradesh a rupee for a kilo. In Amritsar, farmers growing peas are getting Rs 7 a kilo; it was Rs 30 last year. “On November 8, I supported the prime minister’s move against black money. But in two days, I began receiving audio messages, photos and phone calls from farmers all over the country—they were in tears,” said Sharma. The worst hit have been the farm labourers.

Dr Sunil Sinha, principal economist and director of the rating agency India Ratings, said agriculture had been affected in multiple ways. “Demonetisation happened when kharif procurement season was on. Most of the buying and selling happens in cash. Because of the liquidity crunch, farmers could not get fair price for their produce and even had to resort to distress sales. Post harvest earnings have gone down which has also impacted their credit repaying ability. Now, the government has started the cashless drive. But, for people like these who do not understand cards and plastic money, it is going to be very difficult,” he said.

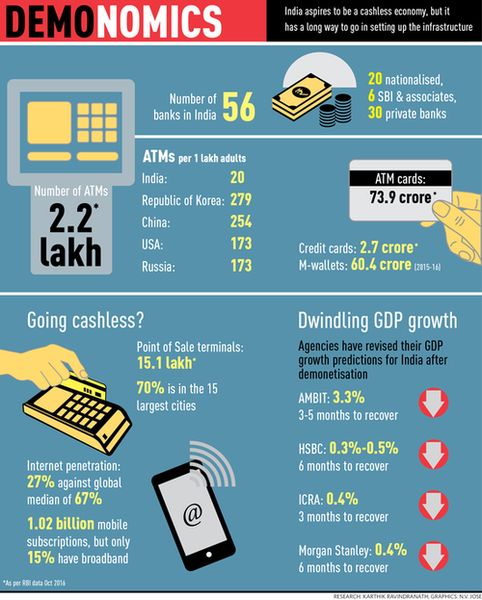

India Ratings has revised the GDP outlook for the financial year. “Earlier, we had put it at 7.8 per cent; but post demonetisation we think the overall GDP will grow by only 6.8 per cent, a 100 bps decline,” he said.

Many experts see the late-found focus on cashless economy as an eyewash. “It is an act of desperation when they introduce even lottery incentives, when they found they had no way of meeting the cash deficit,” said Sharma.

Many people who initially supported demonetisation have changed their stand as there hasn’t been any sign of improvement in the cash flow. Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu, who heads a committee appointed by the Central government to look into demonetisation issues and was a proponent of the move, recently voiced concerns about things not improving.

NITI Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant, however, is happy with the way people are moving towards cashless methods. “There has been a huge spurt in digital transactions since November 9. The use of RuPay has gone up by 316 per cent, e-wallets by 271 per cent, UPI by 119 per cent and USSD by 1,202 per cent,” he said. But there is a catch—only 5 per cent of the total population uses digital cash.

People clearly are resorting to cashless methods because they have been deprived of notes. “Low-value payments through debit cards have increased, and there is a substantial increase in the number of debit card transactions as opposed to credit card,” said Murali Nair, senior vice-president (market development), South Asia, of the payment technology company Mastercard.

Much like retail stores attracting people with draw of lots during the festive season, the NITI Aayog rolled out draws that offer cash-backs to lucky consumers. With a low transaction amount range (from Rs 50 to Rs 3,000) and the platforms chosen for the scheme—RuPay, Aadhaar-based payments, Unified Payment Interface and Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (a mobile banking platform for feature phone users)—the target group is clearly those living in villages and small towns.

Rather than incentives, however, the need of the hour is ramping up the digital infrastructure in the country. “Last-mile connectivity is a huge problem,” said Thyagarajan Seshadri, president of banking relations at Electronic Payment and Services Private Ltd. “We have 6 lakh villages; only 2.5 lakh of these have a bank or an ATM. A lot of benefits will accrue once India Post Payments Bank is formally launched.”

For now, the vulnerable sections everywhere have been rendered moneyless. Take, for instance, Delhiite Sanjay Ahir. He wore a dirty kurta and said he did not have the money to buy a detergent soap. He has been looking for a job after being fired as a parking boy. “Parking has been made free because people have no cash. The contractor is not making money, so why would he pay me,” he said. Ahir used to earn Rs 300 a day. He has never used his bank account and has no clue what Paytm is.

In the tea estates of Assam, workers get cheques as salaries. They have to travel long distances to encash them. Apparently women are affected more than men. Said Ratna Vishwanathan, CEO of Microfinance Institutions Network, “The government is talking about smartphone-based transactions. But while most of the microfinance borrowers are women, the phones are generally with male members of the family. Also, the no-frills Jan Dhan accounts do not come with chequebooks.”

The urban middle class and the elite, on the other hand, are more or less insulated from the trouble as they use plastic money and digital wallets. So the winter vacation, the Christmas and New Year parties and the gifting happen without a hitch. But there is a slight change in the shopping habit—the cash crunch has resulted in losses for the standalone luxury stores and high-end malls, while the e-commerce sites have gained. “Customers who earlier preferred to go to brick-and-mortar stores are now coming online. Mobile wallets have been influencers in making people go online because of the cash-backs and discount coupons. We have seen 50 per cent growth in transactions through Paytm,” said Amit Dutta, co-founder of Luxehues.com, a luxury portal..

A few new urban businesses appear to have benefited by the cashless drive. Sakshi Vij, founder and CEO of Myles, a rent-a-car service, said people had started using digital cash more frequently and smartly. “A lot of people earlier were buying cars and would pay a large component in cash. Now, they prefer to hire a car and pay rent by card,” he said. This should make a stronger case for premium segment vehicles, as nobody wants to be caught spending on luxury, with the income tax department keeping a close watch.

The tax sleuths, in fact, have been working overtime since the demonetisation announcement. There was a spate of large recoveries in Kolkata, Bengaluru and New Delhi, including in bundles of the new 2,000-rupee notes. And the government’s claims about pumping into circulation some Rs 4 lakh crore of new legal tender sounded hollow as people found it almost impossible to lay hands on it.

Where has all the cash gone? A bank manager in Delhi said, before demonetisation if people withdrew Rs 1 crore a day, they also deposited about Rs 80 lakh or Rs 85 lakh. “Now they take new currency, even if much less than in the past, and would spend it here and there. But some people should be depositing also. That is not happening.” From November 9 to December 16, the cash deposit (other than the demonetised currency) in his branch was just Rs 5,000. His hunch is, it is going into the kitty from where some people will exchange old black money for a 30 to 40 per cent commission.

There are whispers that the immediate gainers of demonetisation have been crony capitalists running digital businesses. And it remains to be seen if people believed that Modi fought and won his war against black money. According to the government, the black money disclosed under the Income Declaration Scheme was Rs 67,382 crore. It was peanuts compared with the quantum in its estimates, making a restive nation ask whether their pains were worth the gains.

It was then that the narrative seemed to lose its fizz and the focus moved to cashless India. Ironically, a large part of India has gone literally cashless—both digital and real.

WITH VANDANA