Narendra Modi has gambled with money, literally. He thinks the gamble will pay off and that he will hit the jackpot—the jackpot being the state of Uttar Pradesh.

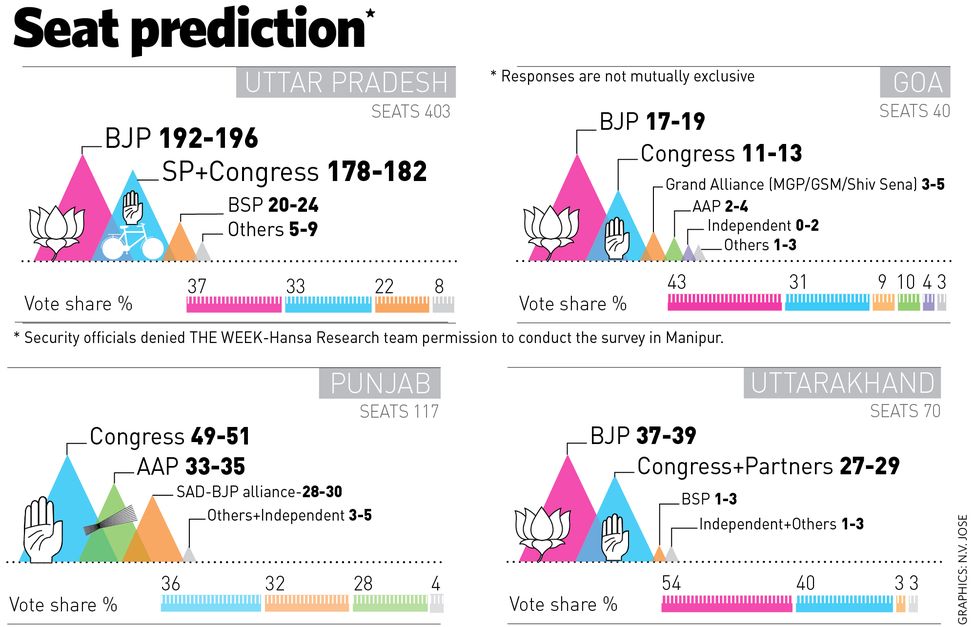

An opinion poll held by Hansa Research for THE WEEK suggests that seven out of ten voters in Uttar Pradesh think it was a good gamble—to try and flush out black money—but not good enough to reward him with the jackpot. Modi will have to fight a post-poll casino brawl and get it. His party, the survey shows, is likely to get less than half the seats in the UP assembly. He will need a handful more—less than ten—to get the majority.

Giving him a run for his money-gamble is Akhilesh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party, which has tied up an unprecedented alliance with the Congress, its old foe. The alliance is likely to get very close to the BJP’s tally—just a ‘handful’ less.

As in the Gangetic plain, the picture on the Indus plain, too, is promising to be one of instability. THE WEEK-Hansa Research survey shows that the ruling Akali Dal-BJP alliance is likely to be voted out, but the voters are not giving the Amarinder Singh-refreshed Congress a majority. He too will need a handful—picked or plucked from other parties in a post-poll brawl. No different is the picture in BJP-ruled Goa, where our survey suggests that the BJP will need one to three more seats to gain bare majority. Only Uttarakhand, where most political pundits have been giving the Congress a fair chance, is seen in the survey as a sure state for the BJP.

In short, a few handfuls will decide the fate of three of the five states going to the polls next month.

As the campaign progresses, the scene might change from what our survey shows. For all you know, the political parties could still draw lessons from the survey and change their strategies. In fact, all the participants will be striving hard to prove us wrong. (Admittedly, not a comfortable thought for us.) The SP-Congress alliance could harp on the hardships faced by the people in a high-decibel campaign and make the voter recall his pain of cashlessness. Modi could step up his surgically striking rhetoric, beat his 56-inch chest further, and even drive the Hindu-Muslim wedge deeper for a communal polarisation in the land of Ram and Krishna. The Aam Aadmi Party could still spoil the Congress’s chances in Punjab by unleashing a campaign against turncoats like Navjot Sidhu, just like it did in Delhi against avsarvadi (opportunist) Kiran Bedi.

There are many such imponderables. Yet, the survey buttresses certain points of conventional political punditry. For instance, the SP’s young chief minister of UP, who has emerged victorious from a bitter family feud against the party’s largely discredited old guard, continues to draw support from the state’s aspiring youth, whereas Modi’s BJP is more popular among the middle-aged who have lived through the vicissitudes of the mandir-masjid strife, the rise and fall of backward and dalit-based parties, communal tensions and terrorist fear. The BJP seems to be holding on to its vote bank of forward castes, and also drawing support from others, such as Jats, Gurjars, Kurmis, Lodhis and Kushwahas. This has pushed the SP-Congress alliance to rely solely on the Muslim-Yadav constituencies, plus the smattering of ‘ancient’ Congress votes. The BJP’s biggest handicap in UP seems to be its inability to project a chief minister, to take on the energetic Akhilesh Yadav.

In Punjab, which is witnessing a three-cornered fight for the first time, the survey finds the young voters favouring the AAP, and the elders (above 40) going for the 70-year-young Amarinder. The Akali-BJP alliance is disfavoured particularly by the forward caste Sikhs. The new entrant AAP has received good support among the Jat Sikhs and the dalit Sikhs. The first-time voters in Punjab are by and large supporters of the AAP, but the experienced voter has very little discontent with the tried and tested parties.

While the Congress has been losing the Muslim votes in the north, it is still managing to hold in the south, as the survey in Goa shows. The three communities of Goa seem to be getting divided among the three parties, with the BJP holding on to its Hindu voters, the Congress to its Muslim voters, and the AAP attracting Christians who were mostly with the Congress. The AAP’s projection of Elvis Gomes could also have helped this Christian swing. Goans seem to be miffed with Modi’s cash-strike, which has affected tourism.

In Uttarakhand, the recent desertion of senior leaders has left the Congress fort solely in the hands of Harish Rawat. Moreover, as political observers say, the BJP is hitting the right chords in the state with its claims of having delivered on the One Rank One Pension promise and executed strikes against Pakistan. After all, the small state has a huge population of ex-servicemen and has lent the names of two of its regions—Garhwal and Kumaon—to two proud regiments of the Indian Army.

Overall, what do the survey results portend? Based on the results one can hazard two predictions—one short-term and one long-term.

If the survey results tally with the actual results, Narendra Modi will find it hard to get his man in the Rashtrapati Bhavan in July. Even with these many seats, he may just about manage 40 per cent votes in a presidential poll. Which means he will have to seek a candidate who would be acceptable to his allies too.

In the long term? Well, Modi may not be able to realise his dream of one-nation-one vote, his new slogan for ringing in a system of holding simultaneous elections to Parliament and the state legislatures. Such a changeover will require major amendments to the Constitution. A fractured political landscape across the multitude of states may not yield him those amendments.

In other words, electoral instability, if not political instability, is here to stay for a while longer.

Methodology

A large scale sample survey of 24,256 eligible voters across Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Uttarakhand and Goa (age 18 years or more and enrolled in the electoral roll) was undertaken in January 2017.

Computer Aided Personal Interviews were used to ensure better quality of questionnaire administration by controlling the order in which questions are asked through a pre-programmed script and not leaving it to the discretion of the interviewers.