Did they just declare another holiday? I don’t want a special class on Saturday,” said my seven-year-old son, disturbed and amused at the same time. “Who are these people? Why are they burning buses?” he asked, watching the violence on news channels. I had the same questions. A schoolmate from Pune pinged, “Hope it’s not a repeat of 1991!”.

For me, as a schoolgirl, the Cauvery row had only meant holidays. But the violence reported in newspapers had been unsettling. The hatred for the “water snatchers” came naturally to innocent kids and immature adults, thanks in part to cunning politicians. When asked about it, the elders at home could only sigh. Little did we realise that a water dispute had pitched Kannadigas against Tamils. The political opponents of the then chief minister S. Bangarappa had alleged that the anti-Tamil violence—that claimed lives, destroyed property and led to exodus of Tamils—was state-sponsored. But what every peace-loving Kannadiga knew for sure was that the opportunists had won.

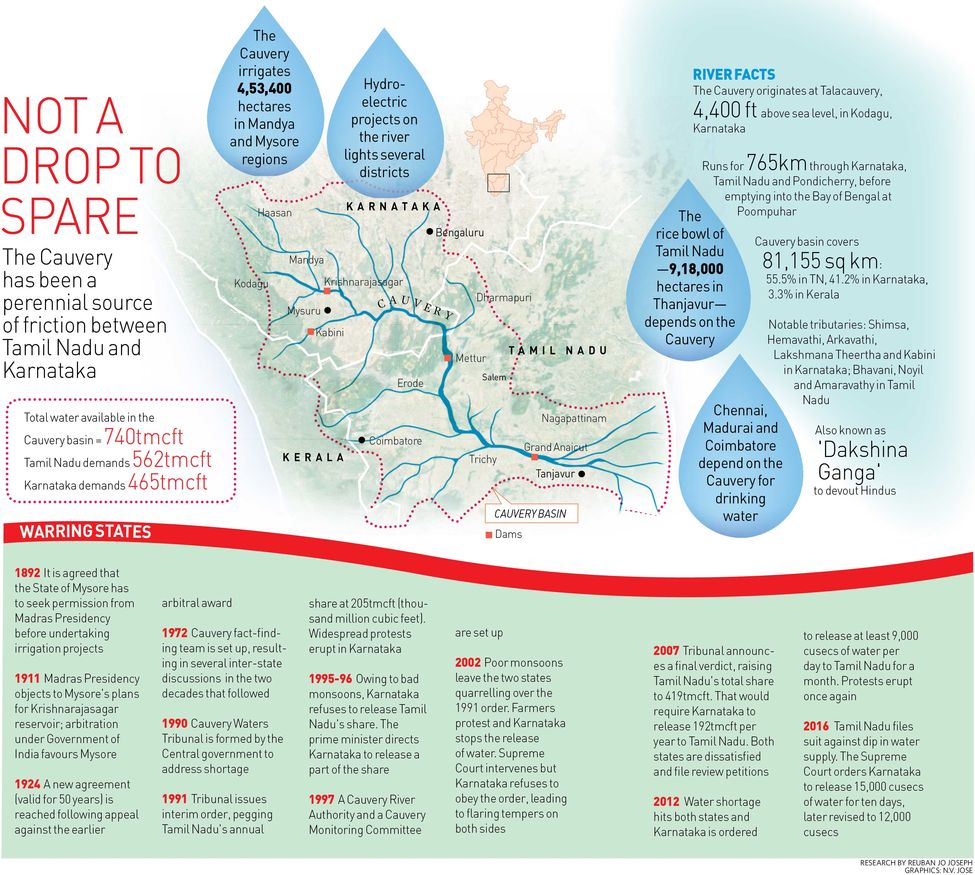

On September 12, familiar visuals of arson and mob fury flashed on television screens, soon after the Supreme Court spelt out the verdict—“Karnataka to release 12,000 cusecs of water to Tamil Nadu daily, till September 20”. Farmers in Karnataka, who had completed sowing in five lakh hectares, were distraught at the thought of having to part with more water for the samba (rice) crops in Tamil Nadu. Buses were torched, stones were flung at buildings and the police, and roads were blocked. Tamils were the target. Curfews were imposed in some parts of the state and two people were killed in Bengaluru. One was shot in police firing while another jumped from a three-storey building to escape police lathi charge.

A familiar city had become a total stranger. Mobs destroyed the sense of security one experienced in the once sleepy city which, even after the IT boom, retained its reputation as a peace-loving place.

Newsrooms in Bengaluru came alive, but the media decided to play down the violence to prevent a flareup of emotions. But the lure of TRPs took over. Many journalists held on to their conscience, fighting the temptation to share the (unverified) visuals of rioting, lest it disturb peace. Netizens, surprisingly, exercised restraint and social media ensured rumours were countered with appeals for peace and warnings to mischief mongers.

Fired up over water: Charred remains of buses in Bengaluru | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Fired up over water: Charred remains of buses in Bengaluru | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

As violence spread rapidly to Mysuru, Mandya and Hassan, there was little doubt that it was an organised unleashing of terror. The Central Reserve Police Force and Karnataka State Reserve Police descended on the streets of Bengaluru. Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah and his Tamil counterpart J. Jayalalithaa wrote letters to each other seeking protection for their people and property. After a quick location check of my extended family, I sent messages to my non-Kannadiga friends stranded in their offices, telling them to stick to English, leave their Tamil Nadu registration vehicles in office and reach home safely. Paranoia had set in.

The Cauvery has always been like family, bringing only fond memories. Paschimavahini in Srirangapatna is where the ashes of our beloved are immersed. The tube rafting along the backwater canals in Pandavapura amid lush sugarcane fields, the memories of watching film shootings, the gushing and whistling sounds of the river in the Visveswariah canal at Krishna Raja Sagara Dam, are all testimony to this unique bond. Cauvery nammadu (the Cauvery is ours) is no mere slogan when it comes from the heart of a Cauvery basin dweller.

But now, once again, as part of a decades-old water dispute, a verdict on sharing water during a distress year has fuelled regional politics, hijacked peace and made farmers on both sides vulnerable.

In 2007, the final order of the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal was out and was gazetted in 2013. It directed Karnataka to release 192 tmc to Tamil Nadu annually, which is measured at Biligundlu, on the border. When there is a good monsoon, Karnataka allows free flow of water from its reservoirs, which exceeds both the expectations of Tamil Nadu farmers and the stipulated quota of water. The water war begins only when the monsoon fails. The upper riparian state finds it difficult to adhere to the month-wise allocation, and the lower riparian state, insisting on compliance, knocks on the Supreme Court door, bypassing the supervisory committee constituted to monitor and review the situation.

Police disperse pro-Kannada activists during protests | PTI

Police disperse pro-Kannada activists during protests | PTI

A decade into journalism, I ventured into the troubled waters, painstakingly read the tribunal orders, watched the political speak of parties and the government, argued with legal experts, visited the river basin, and shared the wisdom and concerns of farmers. Yet, I found that every drought year brought a sense of helplessness as the same political games played out, the courts gave predictable verdicts, protests disrupted lives and livelihood, water was released to Tamil Nadu, the state legal team was called names and the Karnataka government got a breather as soon as the southwest monsoon in Karnataka receded and the northeast monsoon arrived in Tamil Nadu.

While the riparian states are still debating the distress sharing formula, and even the total yield in the reservoirs, the tribunal order seems to be more a hurdle than a facilitator. There is an urgent need to expand cultivable area, build additional storages to tap a good monsoon and mitigate water shortages.

Long before it got the IT city tag, Bengaluru had carved a reputation of a friendly cosmopolitan city. While Kannada hardliners rue that Kannada is sandwiched between ennada and ekkada, referring to the huge Tamil and Telugu speaking population, it was never the trigger for violence. Identity politics seems to be the new tool of vested interest groups.

As I sat quietly wondering if the scientific community should find its voice in the cacophony of political rhetoric to end the Cauvery logjam, my son walked in. “If we cannot share, we should create another river for ourselves,” he ruled.