In combative mode: Officers in the infantry (left) and artillery (right) divisions are at loggerheads with the others. Imaging: Job P.K.

In combative mode: Officers in the infantry (left) and artillery (right) divisions are at loggerheads with the others. Imaging: Job P.K.

Lieutenant General Pravin Bakshi, an Armoured Corps officer, is expected to succeed General Dalbir Singh Suhag as the next Army chief. “In all likelihood, he may be the last officer from the Armoured Corps to head the Army if the current promotions policy for lieutenant colonels is allowed to continue,” says an officer from the corps, which is responsible for penetrating enemy defences in war.

There has always been rivalry among the different constituents of the Army, but the hostility created by the current promotions policy has officers of the artillery and infantry pitted against the others.

On social media platforms, retired and serving officers are taking digs at each other. Ordnance Corps officers do not hesitate to remind their infantry batchmates that there are more Ashok Chakra awardees from their corps than from the infantry; Army Services Corps officers dwell on the gallantry of officers like Lieutenant Vijayant Thapar and Lieutenant Neikezhaukuo Kengruse, who died in action during the Kargil conflict; and infantry officers are pointing out that it is their troops who always face enemy fire first during war or ceasefire violations on the Line of Control.

The bone of contention between these arms is the command exit promotions policy, which allegedly favours infantry and artillery officers over others when lieutenant colonels are promoted to colonels.

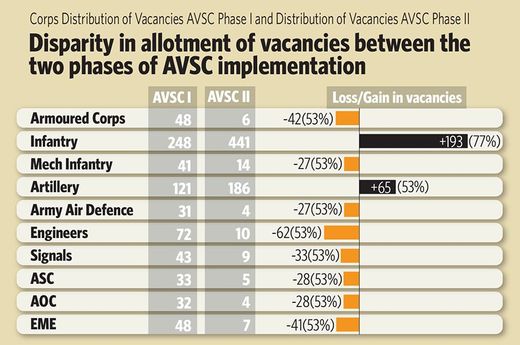

After the Kargil War, it was noted that Pakistani officers heading their units were younger than their Indian counterparts. To restructure the officer cadre and reduce the age profile of battalion commanders, the government commissioned the A.V. Singh Committee (AVSC) to make recommendations. The report, the first phase of which was published in December 2004 and the second in November 2008, gave recommendations on promotions of lieutenant colonels to colonels. In the first phase, 750 vacancies for promotions were allotted to various divisions on a pro rata basis, based on the strength of each division.

In the second phase, 734 vacancies were allotted as per the command exit model policy, formulated in January 2009, where more vacancies went to the younger infantry and artillery officers to lower the age profile of commanding officers. As a result, vacancies in other divisions were reduced. The policy was quashed by the Armed Forces Tribunal. The Army has appealed against the verdict in the Supreme Court. On April 22, the court asked the ministry of defence to file an affidavit stating whether or not it had accepted the policy.

The rift between the officers has widened as the government has stated that the Army, as the employer, has a right to make its promotions policy and that the tribunal should not have interfered in policy decisions. “You cannot win a war with just the infantry and artillery fighting for the country,” says former major Sudhanshu Pandey, a lawyer for officers against the policy. “The Army fights as a unit, which includes officers from all arms and services such as armoured, signals, air defence, engineers and other branches and this policy is totally discriminatory.”

More than 300 officers fighting the policy in court approached the principal bench of the tribunal contending that there was more than a 75 per cent hike in vacancies for infantry officers and a 53 per cent hike for artillery officers, while vacancies for those from air defence, signals, ordnance, service, electronics and mechanical engineering corps were reduced. They argued that the policy was “arbitrary and highly skewed in favour of infantry and artillery as compared to other branches within the Army”.

The tribunal, headed by Justice Sunil Hali, accepted their demands and ordered that the Army consider the cases of the petitioners and others who had been denied promotions based on the policy, and to consider creating new posts for the affected officers.

The officers allege that the arbitrary changes in the promotions policy were made to control and regulate the seniority of officers in such a manner that officers from certain corps would be considered for promotions along with junior officers from the privileged corps.

The architect of the policy, retired Army staff general Deepak Kapoor, refutes charges of favouritism, stating that it was made from the perspective of lowering the age profile of commanding officers. “There was no favouritism,” says Kapoor. “The other services were not able to absorb the vacancies in the first phase and that is why the infantry and artillery could get more vacancies in the second phase. I was the Army chief at that time, but the decision was taken by me in consultation with other senior officers of the force.”

Pandey feels that the policy will also affect the elevation of officers to the ranks of brigadier or above, as there would be fewer officers in the pool for higher ranks. “The new quota policy will have to be quashed as it will create a feeling of inequality,” says Pandey.

The effects of the rift are manifesting on the field, too. For example, infantry officers promoted as lieutenant generals are pushing for a posting in the northern command in Jammu and Kashmir, the only operational formation headed by one of their comrades, Lieutenant General D.S. Hooda. They fear they might face discrimination from superiors in other commands.