During election time in Kerala, every incident gets politicised and eventually leads to mud-slinging between political parties. The gruesome murder of Jisha, 29, a law student, at her house in Perumbavoor near Kochi on April 28 was no exception. Despite the political heat over it, the police are yet to make a breakthrough in the investigation.

The police can blame only themselves for it. The initial investigation was surprisingly shoddy and the police did not seal the crime scene even days after the murder. Nor did they inform the district collector or the revenue divisional officer about the brutal crime. Though there is no legal obligation on the police to do so, it is a usually followed practice.

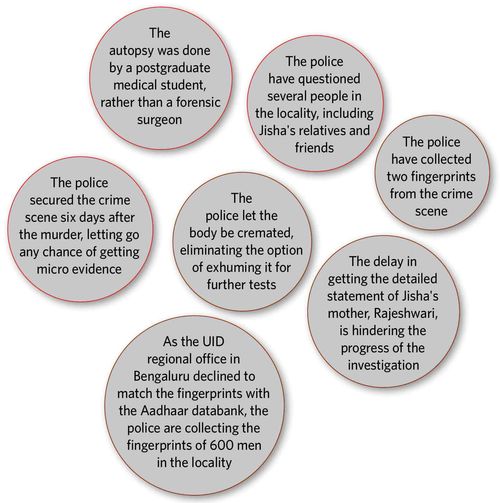

In the absence of eyewitnesses, the autopsy warranted the presence of an expert forensic surgeon. But the police let a postgraduate medical student do it and they did not send the internal organs for forensic analysis saying these were too damaged to be examined. Nor did they take the victim's nail clippings, which possibly had grabbed the killer's body tissue while resisting him. That the autopsy was done by a postgraduate student, rather than a competent surgeon, could be crucial during the trial, as the prosecution is entirely dependent on circumstantial and scientific evidence to prove the case.

Jisha lived in a house on wasteland near the Periyar Valley Irrigation Canal. As the police sealed the crime scene six days after the murder, they lost the chances of getting any micro evidence from the site. Many people, including neighbours, entered the house in those days, and the two fingerprints that the police belatedly collected might prove useless.

The biggest mistake was letting the body be cremated soon after the autopsy. It eliminated the option of exhuming it for further examination. The keeper of the public crematorium in Perumbavoor was reluctant to cremate the body because it was past the working hours, but the station house officer of the local police prevailed upon him. Jisha's mother, Rajeshwari, did not want the body to be cremated. Jisha had got five cents of land from the government under a scheme for dalits and she had started building a house there. Rajeshwari wanted her to be buried in the plot, but the police ignored the request.

The police woke up only after the murder attracted national attention and became a poll issue. Then they started interrogating many people, including Jisha's relatives and friends. The police say she was murdered to take sexual revenge. They suspect that the killer is a psychologically twisted acquaintance or a sex deprived migrant labourer. The killer strangled her with his hands and a shawl, and stabbed her in the face, chest and stomach after raping her.

A neighbour told the police that the day Jisha was killed he overheard her saying “this is why people say you should not be trusted.” Then he heard a scream. Four neighbours told the police that they saw a person washing blood off his hands and dress in the canal. But they came to know about the murder only two hours later when Rajeshwari came home and saw the body.

The police believe the killer knew Jisha well and had the liberty to get into the house. The family led a reclusive life and she would not have opened the door to a stranger. There was no sign of breaking in, either. The police sniffer dog found a pair of slippers near a public water tap nearby. There were traces of cement on the slippers, so it possibly belonged to a construction worker. Hundreds of migrant labourers, mostly construction workers, live in the locality. The slippers have been sent for forensic investigation.

A theory by the police is, the killer reached Jisha's house between 3pm and 5pm on April 28. Though she was alone she let him in because she knew him. She might have given him a glass of water—the police have picked fingerprints from a glass. A verbal fight might have triggered violence, and she was smothered and strangled. Rape was committed after this. He then stabbed her in the face, stomach and genitals.

He might have got out through the backdoor and crossed the canal. The sniffer dog traced this route till the public water tap. He might have escaped in a vehicle from that place. The police have made these assumptions on the basis of circumstantial evidence, statements of witness and mobile call details.

The efforts of the police to match the fingerprints with the Aadhaar data bank, however, had a setback as the regional office of the Unique Identification Authority of India in Bengaluru declined to do it. But the district fingerprint bureau is collecting fingerprints of some 600 men in the locality. But, for now, all fingers point to police callousness.