The Line of Control that separates Indian and Pakistani troops runs through some of the world's most inhospitable terrain. As one moves from the base of the Pir Panjal range towards the north—into the glaciated Great Himalayas and the Trans-Himalayan region—the conditions seemingly get worse. For the layman, used to judging physical discomfort by increasing altitude, Siachen is the final endurance test. Not surprisingly, national and international media often highlight the extreme conditions. In 2007, Myra MacDonald, the Reuters correspondent in India, gave her book on the Siachen conflict a somewhat catchy (and some would say apt) title—Heights of Madness.

Ever since 1948, when the Indian Army pushed back the raiding columns of tribal lashkars from Jammu and Kashmir, the LoC has been a fact of life. From the very beginning, the line, which was only visible on maps and in the minds of men, developed a character of its own. Its defence became synonymous with the protection of every soldier's home, a matter of life and death. In front was the enemy—always probing, looking for weaknesses, waiting to exploit any situation—and behind them the entire country, which went about its day-to-day business, sleeping soundly at night, secure in the knowledge that there were men out there, hundreds, thousands of them, who were peering into gunsights and night-vision devices, looking for any developing threat. After it was established in 1949, this 'thin red line' faced its first organised challenge in 1965 when Pakistan once again tried to force the issue. After the initial onslaught was repulsed, the Indian Army succeeded in altering the LoC by successfully capturing Haji Pir and certain key positions in and around Kargil.

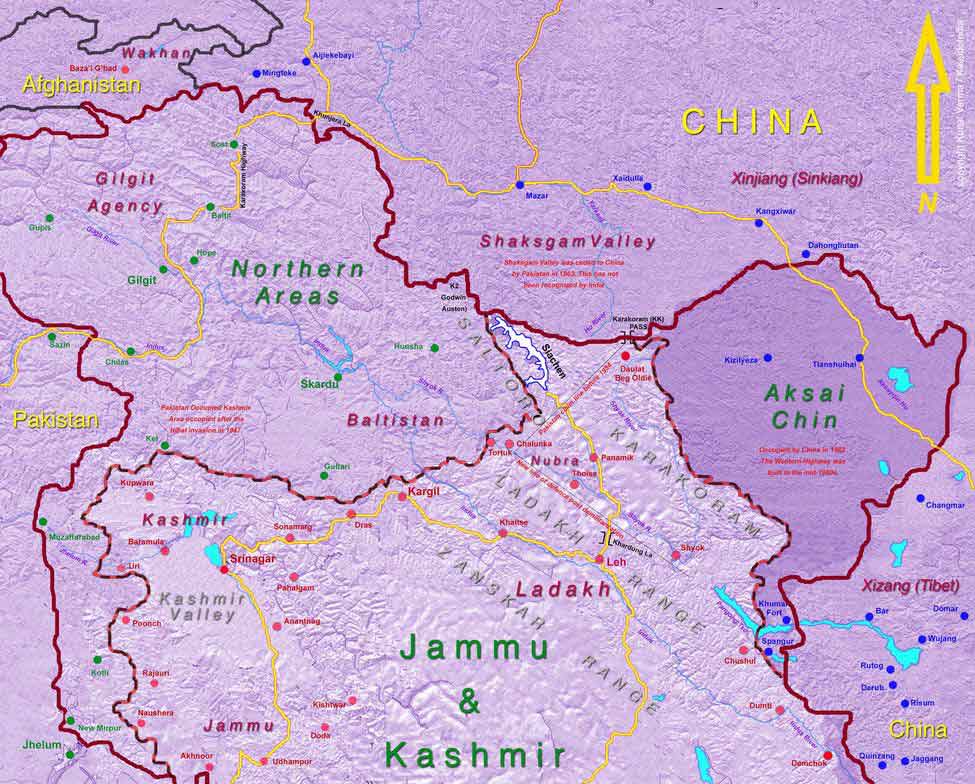

These gains were, unfortunately, frittered away when India decided to 'return' these positions to Pakistan. Six years later, the LoC was once again in sharp focus as the two countries were at war again. Since the emphasis and attention this time was on the eastern sector and Bangladesh, the performance of Indian troops in the Nubra region of Ladakh, along the Shyok river valley, went largely unnoticed. The Ladakh Scouts successfully cleared and pushed back the Pakistanis from the area around Chalunka and Tortuk. Thankfully, this time around, India retained this hard-fought and strategically important area. As a result, when the two Director Generals of Military Operations—Lieutenant General P. S. Bhagat from India and Lieutenant General Hameed Khan from Pakistan—met in 1972, the line that had been drawn in 1949 had to be drawn afresh.

Once again, the border was drawn up to Point NJ9842 on the map, after which the two sides agreed that the boundary would run 'hence north to the glaciers'. In the 1950s through to the early 1970s, it was perhaps natural to see the vast territory to the north as a barren wasteland. Rotary wing aircraft were relatively new combat platforms, and their ability to change the dynamics of high altitude warfare was not a known factor. “The area was so harsh and so difficult, it was seen as a natural barrier and it was decided to leave it alone,” says Colonel Narinder 'Bull' Kumar. “Let us not forget, the first Indian expedition that successfully climbed Everest had done so just five years previously. Very little was known about high altitude conditions, let alone warfare.”

By stopping at NJ9842, Bhagat and Hameed Khan had unwittingly laid an egg that would hatch into yet another conflict a few years later. The 1971 defeat and the formal amputation of its physical self had rattled Pakistan. It was hardly likely to provoke another military showdown with India, so instead it decided to emulate Chinese tactics of 'cartographic aggression'. Drawing a straight line from Chalunka to Karakoram Pass (Daulat Beg Oldi), the Pakistani army laid claim to the entire Saltoro range and Siachen glacier, along with parts of its eastern extremities, an area of approximately 5,000 square kilometres. Taking their cue from the Pakistan army, the US military and NATO countries began to mark these areas as Pakistani territory. “The Americans have always had an interest in the region,” says Lieutenant General Rakesh Loomba, former head of military intelligence. “Even the maps that initially showed Saltoro range and Siachen glacier as being Pakistani territory were issued by the US Air Force.”

To further buttress their claim, the Pakistanis began allowing international expeditions to climb various peaks in the region. The 1978 issue of the American Alpine Journal duly recorded these expeditions and highlighted the fact that Siachen was part of Pakistan. Armed with this information and some maps obtained from German tourists, Bull Kumar immediately obtained permission to mount a reconnaissance expedition into Siachen.

By the time the Indian Army expedition reached the Nubra valley in 1978, the area to the north was literally crawling over with foreign expeditions, most of which were transiting through Bilafond La to Siachen glacier and then onto the peaks on the eastern flank of Siachen. The Indian Army expedition successfully climbed Teram Kangri II and ventured onto Siachen glacier, which had until then only been visited by the occasional Army patrol. It’s a wonder that the Indians didn’t run into a traffic jam, as around the same time there were at least two more Japanese expeditions in the general area.

In a manner of speaking, the 1978 Indian Army expedition marked the beginning of the Siachen operations. On September 20, the first helicopter sortie took off from Leh in support of Colonel Kumar’s expedition, dropping fresh rations at Camp I and Camp II. A fortnight later, 114 Helicopter Unit (which has since flown countless missions in Siachen) was called upon to evacuate a casualty from the advance base camp. The helicopter landed at what is perhaps now known as Kumar, from where they evacuated an officer and a jawan from the expedition.

In 1981, ‘Bull’ Kumar, again at the helm of a full-fledged 55-member expedition, set out from the High Altitude Warfare School. After getting onto the glacier, it took another four days to arrive at the junction of Siachen and Lolofond glacier (the entrance to Siachen via Bilafond La), after which they moved on to where Saltoro glacier meets Siachen. Two more camps were established—east of Sia La in the centre of Siachen glacier and another near a glacial lake. Subsequently, members of the Indian expedition skied up to the ridge and then traversed the 19,000-foot Indira Col along the divide between the Indian subcontinent and central Asia. The team also skied to Turkistan La, Bilafond La, Sia La and the gap between the Peak 36 glacier and South Dong Dong glacier. The team had traced the entire westerly parameters of the Siachen glacier.

Bull Kumar’s 1978 expedition had set the cat amongst the pigeons. The advent of Indian expeditions on the region had started questioning the accepted position that the entire Karakoram range was in Pakistan’s control. The Pakistanis, realising that the Indians were now fully aware of any activity in the area, concentrated all foreign expeditions to the area around K2, staying well clear of the region east of Bilafond La.

“We bungled,” says Kumar, 34 years after having led the expedition that defined the new boundary. “I had sought permission to head for the K2 base camp. Had that been our subsequent thrust, the Pakistanis would have nothing to hang their hat on and the Siachen glacier would have remained to the east of the new LoC. Unfortunately, Army HQ was paranoid about us venturing even one degree to the west of NJ9842.”

General V.K. Singh, minister of state for external affairs and former Army chief, supports Kumar’s claim. “In 1984, when we had enough evidence that Pakistan was planning to occupy Siachen, we finally moved onto the Saltoro,” he says. “Not wanting to go against the spirit of the Simla Agreement, we were not looking at occupying Dansum, which would have been the logical objective for the Indian Army. All three major passes, Sia La to the north, Bilafond La in the middle and Gyong La in the south, converge at Dansum, which is a flat valley roughly at the same altitude as Leh and ideal for heli-borne operations. This would have cut off Pakistan from the region altogether and also threatened Khaplu. Incidentally, Dansum was to become the headquarters of Pakistan’s 323 Brigade.”

The reasons for occupying Siachen and committing troops to man posts at heights in excess of 20,000 feet certainly seemed like madness to most observers even then. Owing to a veil of secrecy over the operations, many incredible actions of Indian troops were never reported, nor were the reasons for going into Siachen discussed in public forums at the time.

Treacherous trek: Troops just below Sonam Post on Saltoro Ridge | Shiv Kunal Verma

Treacherous trek: Troops just below Sonam Post on Saltoro Ridge | Shiv Kunal Verma

So why did we go into Siachen in 1984? This was abundantly clear: Siachen was part of Indian territory and cartographic aggression coupled with an aggressive posture by Pakistan could not be tolerated without it impacting our claim over the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir. Given the conditions and the available information, Northern Command planned to occupy the two possible major routes of ingress during the summer months, pulling the troops back once the weather closed in (as was the norm along most of the LoC beyond Zoji La). In 1983, the XV corps commander had done a threat assessment that had exaggerated Pakistan’s offensive capability at the time; the exercise finishing with a flourish in which Khardung La and Leh were threatened.

The exercise may well have exaggerated Pakistan’s offensive capability at the time, but as years passed and the airlift capability of all countries increased dramatically, it became obvious that committing troops and extending the LoC along Saltoro had been a blessing in disguise. Says Lieutenant General P.C. Katoch, who commanded the Siachen Brigade during the Kargil war: “If Pakistan had taken control of the glacier, it would have automatically controlled Saltoro Ridge. We would have then had no choice but to fortify the entire Ladakh range that runs west to east, preparing defences along the Shyok river. The quantum of troops required to do that would be almost fifteen times what we have in Siachen now, plus it would make Leh a frontline town.”

In the eyes of most Indians, Siachen has always been an India-Pakistan issue. However, with the choke points guarded by Indian troops on Saltoro, Pakistan today, at best, has only some nuisance value. The real problem, if any, is the Chinese who are sitting on the northern flank of the glacier, Pakistan having ceded the Shaksgam Valley to them in 1963. The Chinese have already demonstrated in the 1950s that if you leave a vacuum, as was the case in the Aksai Chin, they will simply move in and claim it as their own.

For two decades after clashing with the Chinese in northern and eastern Ladakh in 1962, India had deployed just one division with two infantry brigades along with two wings of the Ladakh Scouts to look after Ladakh. With the Kargil area being looked after by 121 Brigade that reported directly to XV Corps in Srinagar, 3 Division was deployed to guard the border with China. Though there was a lot of noise about inducting troops into Siachen and the costs involved, only two or three infantry additional battalions (a brigade) had to be inducted into the area. With part of this brigade also holding Turtok, by extending the LoC along Saltoro, in real terms it meant holding the area with a minimum number of troops.

That the threat perceptions were changing with changes in technology and airlift capabilities was obvious when, in the mid-1980s, India raised 28 Division under the command of Major General R.K. Gaur with its headquarters at Nimo, a village in Leh. “This put the fear of God into Pakistan, which was convinced the Indians would now roll down the Shyok Valley and cut off Skardu,” says Gaur. However, with militancy intensifying in the Kashmir valley after 1989, the Chief of Army Staff, General S.F. Rodrigues, pulled this division out and deployed it in the Kashmir valley. The resultant void in force levels then encouraged the Pakistani army under Pervez Musharraf to try and move into the Mushkoh, Dras and Kargil sectors.

With 8 Division having to be brought back into the region to fight the Kargil War, India now has two divisions defending Ladakh, which have been brought under the command of XIV Corps headquartered in Leh. “Had we not moved into Siachen, or if, for some absurd reason, we decide to pull out from Saltoro, this force level will almost double,” says Katoch, who has been instrumental in stopping the Track II team set up by the prime minister's office in 2012 to look at the demilitarisation of Siachen. “People who have been advocating pulling out of Siachen, making it a peace park, are simply not looking at the whole picture. Pull out from Siachen and go where? Your next defensive line will then run all along the Ladakh range from Turtok all the way to Pangong Tso in the Chushul area. Having done all the hard work in establishing Siachen as a firm base to hold the Saltoro, that would be the height of madness.”

Over the years, the Indian establishment has had serious problems with defence procurement, and inductions have simply not kept pace with the requirements. The Cheetah helicopter, the workhorse for the Air Force and Army aviation units, continues to fly in the region even though it should have been replaced at least a decade ago. Induction of 155mm guns and problems with ammunition have been pointed out regularly, which will further get strained if yet another force level is required to man the new line of defence. Even the new Strike Corps, raised in north Bengal to counter the threat of the Chinese in Sikkim and Arunachal, has had funding problems.

It is but natural that when accidents happen and soldiers are killed by an act of nature, there will be a certain amount of soul searching and questions will be asked. General V.K. Singh further underlines the point in his book Courage and Conviction: “In the past, there have been serious moves initiated by the previous government at the highest level to pull back from Siachen. If India was to indeed ‘demilitarize’ and pull troops out of what she considers to be her own area, then Pakistan and China have complete freedom to move where they want and the country will be in no position to oppose this. The Indians may not even get to know about it, as happened in Kargil, for there will be ‘no eyes on the ground’. Should this happen, the whole of the Nubra Valley becomes vulnerable—for Turtok can be outflanked and an invading column can come straight down the glacier.”

Besides, when facing eastwards from Siachen, there are routes available through the Rimo group of glaciers to cut through to Karakoram Pass. Tomorrow, if there is a confluence of interest between China and Pakistan to move into Ladakh, then it will be very difficult to stop them. The recent ingress by the Chinese into the Daulat Beg Oldi area on the eastern flank of Siachen underlines the fact that with improving technology, there is no area in the region that cannot be accessed. India simply cannot make the same mistakes it made that led to the Chinese debacle in 1962.

Shiv Kunal Verma is the author of The Long Road to Siachen: The Question Why (Rupa & Co. 2010) and 1962: The War That Wasn’t (Aleph 2016)