Is it a sojourn through the mind of one stalwart through the eyes of another or a conversation between two brilliant minds through “mind images” constructed over the past four decades? The 90-minute documentary on Dadasaheb Phalke awardee Adoor Gopalakrishnan titled Images and Reflections: A Journey into Adoor’s Imagery by Kannada filmmaker Girish Kasaravalli is a heady mix of intrigue and insights.

“I was not interested in a biographical account but in the creative person as Adoor comes across through his work,” says Kasaravalli, who was reluctant to make the documentary when the Films Division approached him. “Being a filmmaker, I was keen to understand the politics and philosophy he [Adoor] constructed through the images and reflections. Here again, I am referring to the images created in the mind and not the visuals.”

So, how did the documentary finally happen? “I was apprehensive as I am not a documentary filmmaker and moreover Adoor is a giant of Indian cinema,” says Kasaravalli. “Adoor, however, insisted that I do the film. ‘Do it your way,’ he said.”

The film turned out to be a great experience for Kasaravalli. After watching the premiere, which was held in Thiruvananthapuram on April 25, Adoor was overwhelmed. “He told me the film came out good because I was not a documentary filmmaker,” says Kasaravalli, who is taking the film to Bengaluru next.

Apart from being pioneers of new-wave cinema, are there any other similarities in the works of the two filmmakers? “No. We are poles apart,” says Kasaravalli, who has directed 15 films, of which four won the National Award. “Adoor’s work reflects minimalism in art, austerity in images and a cinematic language that lifts a documentary’s history to a new level where it becomes contemporary and the local flavour attains universality. He is a minimalist and I am inclusive in my approach. We admire each other’s work but our styles are different. Be it Shyam Benegal, Mrinal Sen, Adoor Gopalakrishnan or myself, we have different styles. Perhaps the only thing common is that our works reflect the contemporary world without compromise.”

During the making of the documentary, Kasaravalli realised that his interpretation of Adoor’s work was quite different from that of the filmmaker himself. “The film is based on my interpretation, perception and perspective of Adoor’s work as we both were sometimes in agreement and mostly interpreting it differently,” says Kasaravalli. “I decided to do it in a different format. I chose to stick to my interpretation. I discussed the approach with my friends... senior filmmakers.”

Wheeling back and forth along the memory lane to understand the compulsions of Adoor, the filmmaker, was not easy, says Kasaravalli.

“I have known Adoor for 45 years and it helped,” says Kasaravalli. “We used to chat and discuss each other’s films. I went through all his interviews and read two books on him. I also watched all his 11 films again.”

So, what does Kasaravalli think of Adoor’s style of filmmaking? “It is unique. His films have socio-political backdrop, but he never takes an issue or system head-on,” says Kasaravalli, who did not touch upon the documentaries made by Adoor.

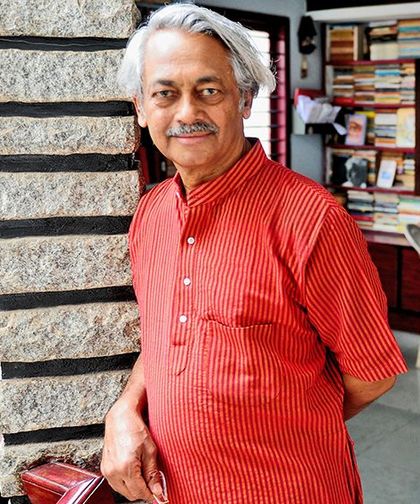

League of legends: Girish Kasaravalli | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

League of legends: Girish Kasaravalli | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

The film was made in an unconventional way. “There was no script. I did interviews to find out important details, experiences and compulsions of the filmmaker,” says Kasaravalli. “I built a narrative and then shot visuals at different locations. Later, I did a lot of random shooting with Adoor. I had to learn and unlearn many things. The narrative has many short interviews of Adoor, his daughter Aswathi Dorje, his sister, journalists Gouridasan Nair and Uma da Cunha, film critic Maithili Rao, actor KPAC Lalitha and historian K.N. Panicker.... Adoor has worked with many music directors. And I have used soundtracks and dialogues from his films as interludes in my film.”

Kasaravalli revisited many locations like Pallickal, where Adoor was born, Alappuzha, where two of Adoor’s films (Naalu Pennungal and Oru Pennum Rendaanum) were shot and Thiruvananthapuram, where he currently resides.

He divided the film into five chapters, each named after an Adoor film. “The last segment, Anantharam, is a reflection on social, political and family institutions,” says Kasaravalli. “Adoor has had many influences in his life—from his family, background, cultural and political realities of Kerala, his film institute days and, most importantly, the influence of Mahatma Gandhi and, of course, the world masters, which is reflected in the aesthetics and content of his work.”

Kasaravalli cherishes the fact that two of his films are on Adoor’s list of five best films. “Two years ago, Adoor mentioned two of my films—Nayi Neralu and Kanasemba Kudureyaneri—as his favourites. Though I have great admiration for all his works, if I were to reciprocate the gesture, I would pick Mukhamukham and Anantharam. Mukhamukham reflects on the splintering of the Left party. He used magical realism to show the time leap in history and socio-political realities. It is my favourite film as it opened avenues for me as a filmmaker.”

Kasaravalli, who took a four-year break from filmmaking to make two documentaries, earned accolades for his first one on writer and thinker Dr U.R. Ananthamurthy. Titled Ananthamurthy: Not a Biography But a Hypothesis, the film released in 2012 and won the special jury prize at the National Award. “If I have tried to interpret Adoor through his work, I tried to decipher the thinker in URA. I tried to recount his short stories, novels and poems through his thoughts,” says Kasaravalli, who made his directorial debut with Ghatashraddha (1977), which is based on URA’s novella on a young pregnant widow.

So, is cinema a mere commentary on the changing socio-political realities or is it a catalyst for change? A filmmaker is a political thinker but not a partyman. He is the conscience-keeper of society, so he must respond. He cannot afford to be blindfolded, says Kasaravalli. “Even Adoor’s films have seen that transition,” he says, “from a linear narrative to non-linear episodic and austere narration to, perhaps, accommodate the complexities in social, political and personal spaces.”