Dreamer, dancer: Amiruddin Shah | Amey Mansabdar

Dreamer, dancer: Amiruddin Shah | Amey Mansabdar

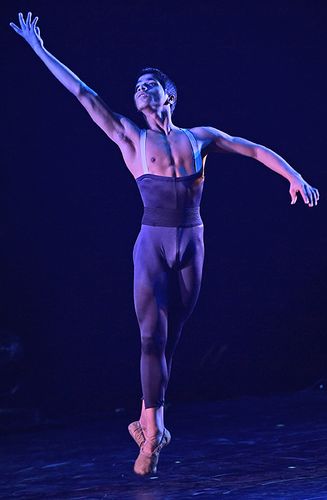

It would be the first-ever stage performance of Amiruddin Shah later that evening, at the St Andrew’s Auditorium in Bandra, Mumbai. It is the annual performance of The Danceworx Performing Arts Academy, and Amir has a two-minute solo slot. We catch the 15-year-old ballerino just before his final rehearsal—he is a little anxious, but confident that his ballet performance would be top-notch.

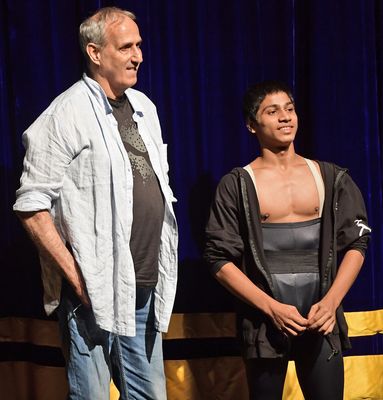

Right across the stage sits an aged man, in the front row, closely watching him rehearse. He looks annoyed when I approach him. He gets up, walks towards the stage and calls Amir. He whispers something to him, comes back, and takes his seat. Amir begins his performance again and ends it to the man’s applause. But he approaches Amir again, and animatedly tells him how his body movement can be bettered. He goes back and sits again. This time, he turns to me and smiles warmly, inviting me to sit next to him. As anxious as Amir, he thinks the lights on the stage can be confusing for Amir. “After all, he is performing under the lights and in front of an audience for the first time. He needs to be on stage a little more to feel at home,” says Yehuda Ma’or, 73, an American-Israeli ballet coach who took Amir under his wings almost two-and-a-half years ago.

Amir was only six when he started enjoying dance, though as a spectator. His father is a welder and his mother used to work in a garment factory. “Now she is a homemaker,” he says after a lot of thought on whether homemaker is the right word to use. “I had seen people dancing on shows like Dance India Dance [DID] and really liked it.” Growing up in the slums of Sanpada, Mumbai, he would watch the show at any neighbour’s house as there was no TV at his home. One good thing about his family, says Amir, the youngest of five brothers and two sisters, is that there was no restriction on pursuing dreams. Maybe that is why one of his brothers is a rifle shooter and another is pursuing acting.

Amir was quick to pick up a few steps from the TV shows, entertaining the neighbourhood kids with back-flips, cartwheels, a few steps of B-boying and some hip-hop. “I was desperate to become a dancer, so much so that I went for DID auditions at least thrice.” He often thought that going to DID may change his family’s fortunes. Once, he stood in the audition queue for more than a day. But he was never selected. His past failures haven’t bogged him down. If the motivation then was only to become rich, his dream now is to dance on a world stage.

Amiruddin Shah | Amey Mansabdar

Amiruddin Shah | Amey Mansabdar

Ma’or spotted Amir during a session at Danceworx Academy, which has scholarship programmes for the not-so-privileged kids. “Ashley Lobo [who runs Danceworx] had told me about him. Once I focused my attention on him, I realised his body is perfect for ballet,” he says. He started training Amir and Manish Chauhan, 22, (another Mumbaikar from a humble background). While training under him, they both got a one-year scholarship to train at Oregon Ballet Theatre in Portland, United States. The duo also featured in Sooni Taraporevala’s virtual reality film, Yeh Ballet.

“When I started working with Amir, I realised that he is very focused and loved doing this. Where people usually take nine years to learn the language of ballet, it took him only two-and-a-half,” says Ma’or, who calls the natural flow of Amir a “little freaky”. “It is like there is a soul of a ballet dancer in him.” While Manish is still completing his scholarship in the US, Amir came back to India in four months. “He couldn’t understand English well, neither did he speak the language. He was a little withdrawn there,” says Ma’or. “Also, the school only began at four in the evening. I felt his time wasn’t being utilised.”

His parents were a tad disappointed about his return, but Amir says he learnt a lot in his short stay in Portland. “I learnt to survive,” he says. “You have to catch the combination in the blink of an eye. Everything is super quick.”

An eye for talent: American-Israeli ballet coach Yehuda Ma’or says Amir has the soul of a ballet in him | Amey Mansabdar

An eye for talent: American-Israeli ballet coach Yehuda Ma’or says Amir has the soul of a ballet in him | Amey Mansabdar

As they say, when one door closes, another opens. A month ago, the American Ballet Theatre invited Amir for a one-year scholarship programme, followed by an offer from the Royal Ballet company in the United Kingdom. But Amir has chosen the former, and will leave for the US with Ma’or in the last week of August. Cipla non-executive chairman Yusuf Hamied will fund Amir’s expenses in the US for a year.

According to Ma’or, Amir has reached a place where he cannot help him anymore. Also, it is not easy to train him in Mumbai. “We have to hire small rooms with cement floors in the basements so that I can spend two hours coaching him. But it can’t work like this. He has to be in a proper institution to excel,” he says.

Ma’or is taking care of a lot of Amir’s needs—from educating him to buying ballet shoes for him. He has hired a tutor to teach him English, science and general awareness for two hours a day. “Now he can read and write a bit in English, but he needs to learn more,” he says. Ma’or recalls how his protege was caught unawares in many situations in Portland. “When you are with other kids, they talk about a lot of things. Like, he wouldn’t know Moscow or Paris, or the number of continents, or the difference between waltz and mazurka. He needs to learn that.” Though Amir wasn’t much interested in studies, he is pursuing it because he wants to excel in dance. Now, he knows a few French terms associated with ballet.

Amir is looking forward to his stint at the American Ballet Theatre where he will train under Sascha Radetsky (Charlie of Center Stage, the film that released in 2000). Incidentally, Sascha was trained by Ma’or earlier. Amir plans to extend his stay and become a principal dancer at the theatre in the next three years.

Amir’s parents missed his first stage performance. He has other plans for them. “I will take them to the biggest opera performance,” he says, with a twinkle in his eyes.