Somabhai Raval was barely seven when prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru laid the foundation stone for the Sardar Sarovar Project at Kevadia Colony in Gujarat on April 5, 1961. A resident of Fatehpura village in Patan district of north Gujarat, Raval is not well educated. Till seven years ago, when construction of a minor canal near his field began, he had not heard that the government was harnessing the Narmada waters for the Sardar Sarovar Project.

The canal near his field was completed two years ago, but Raval’s 44 acres remain parched as ever. “Where will the water come from?” he asks, pointing to a kilometre-long furrow bordering his field. The furrow has not been joined to the canal and is filled with trash. “There is no flow now,” he says. “I will clear the trash when the water comes.” For now, he and his family of 10 depend on water from a borewell, which costs them one-third of their income.

On September 17, on the occasion of his 67th birthday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled a plaque dedicating the Sardar Sarovar Dam to the nation, saying Gujarat would soon witness a green revolution. But farmers like Raval, who have been waiting decades for irrigation projects to bear fruit, do not expect any change in the near future.

The BJP has for long been criticising the opposition Congress for its alleged failure to increase the dam height when it was in power. But, in the past 22 years, during which it was in power, the party has done little to complete the network of canals. “The Gujarat government had been getting funds from the Centre under accelerated development schemes for irrigation,” says Himanshu Upadhyaya, an expert on public finance and water policy. “But the money was not used to build canals.”

Medha Patkar, whose Narmada Bachao Andolan opposes the project, had been claiming that the Narmada waters would never reach the parched areas of Gujarat. Considering what Raval and farmers like him are saying now, she seems to have been right, at least to some extent. The state government’s own records say that 25,000 kilometres of canals need to be built.

The project is yet to benefit far-flung areas like Kutch, Saurashtra and north Gujarat. In fact, even canals in relatively nearby areas—such as in Hansalpur, 87 kilometres from Ahmedabad—remain unfinished. “We used to draw water from a small pond using pumps,” says Bhikhabhai Bharwad, a 65-year-old farmer in Hansalpur. “Now the pond is part of the upcoming Maruti Suzuki plant.”

Like Raval, Bharwad, too, now depends on a borewell for water. He says that, even though the government has not completed the canal network to supply water to farmers, it has laid an underground pipeline from Modhera, about 15 kilometres from Hansalpur, to the Maruti plant.

Over the years, the state government has largely focused on supplying water to industries and urban areas. Newer regions have been added as beneficiaries of existing projects. A classic example is Sabarmati Riverfront, an infrastructure project on the banks of the river Sabarmati in Ahmedabad. The water for the project is drawn not from the Sabarmati, but from the Narmada.

BJP spokesperson Bharat Pandya, however, maintains there is nothing wrong in diverting water from the Narmada for the benefit of housing societies in Ahmedabad. He said it had resulted in saving electricity, which would otherwise have been spent for drawing water from other sources. According to Pandya, it was the Congress’s mistake that it did not think of the plan earlier.

Experts, however, disagree. “Planned priority work is not happening,” says Himanshu Thakkar of the NGO South Asia Network of Dams, Rivers and People. “Neither Ahmedabad nor central Gujarat was the priority. And, if water tables had to be increased or electricity bills had to be reduced, there was no need to build such a large dam. There are other options available.”

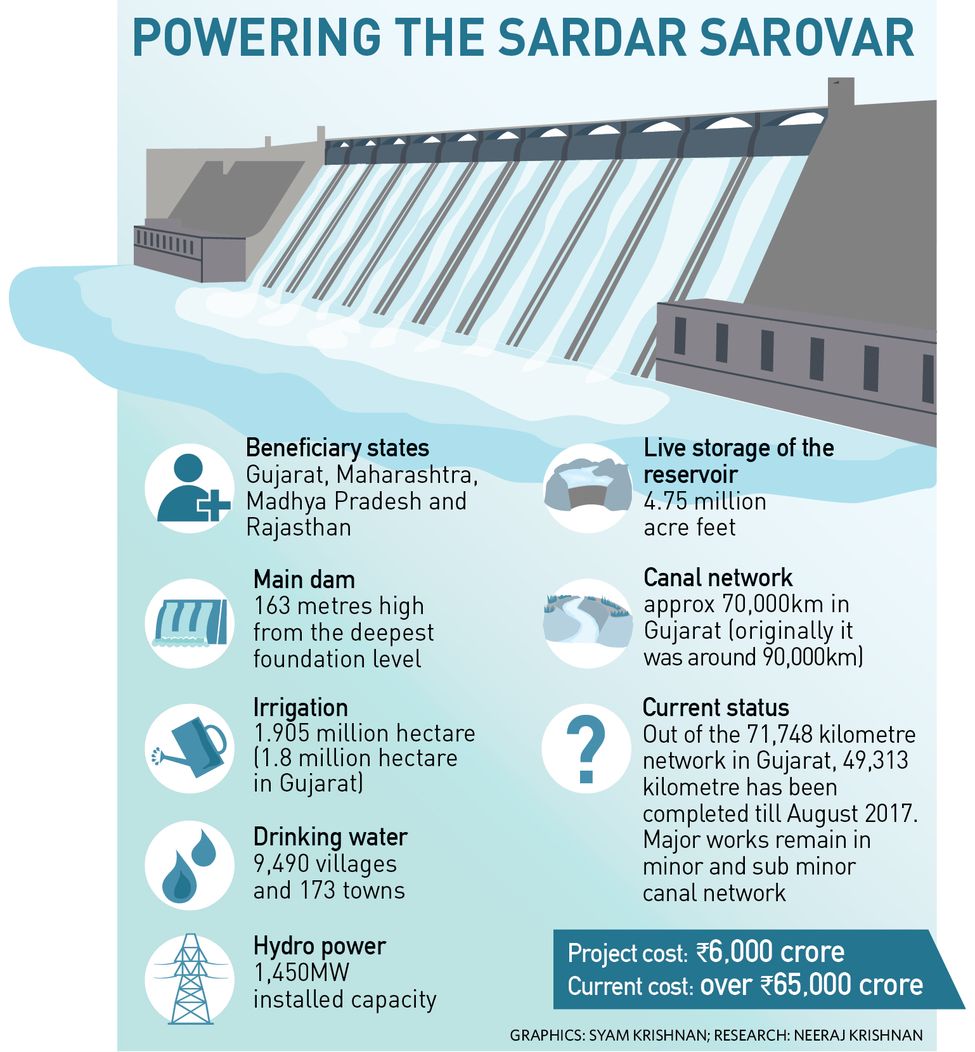

Former chief minister Suresh Mehta says the state government is guilty of criminal negligence, and it reduced the length of the canal network from around 90,000 kilometres to 70,000 kilometres without consulting the Narmada Control Authority, as was mandatory. According to him, the network is still incomplete because the government did not follow the tried and tested “vertical integration approach”, wherein minor and sub-minor canals are constructed simultaneously.

In the run-up to the assembly polls, the BJP would have to field tough questions regarding the project. Like, for instance, why there is no increase in the area irrigated despite the government having spent crores. The government’s own records show that the total land irrigated remained unchanged at 2,07,057 hectares in 2012-13, 2013-14 and 2014-15.

Also, sources say as much as 40 per cent of the water in existing canals are illegally diverted. At Asjol in north Gujarat, for instance, farmers allegedly divert water from the Narmada Main Canal to neighbouring fields. “This has been going on for years,” says Poonambhai Solanki, a resident of a village near Asjol. “People do not get water in their fields and hence they have to resort to such tactics.”