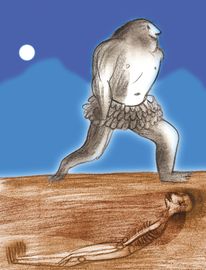

There is no such thing as a new idea,” remarked American writer Mark Twain. Re-living the “easy-come-easy-go” hippy lifestyle, hanging custom-made wall hangings or growing organic food in the backyard are not new fads. The inhabitants of Çatalhöyük in modern Turkey have “been there, done that”—more than 9,000 years ago. Stone age people are seen as unwashed savages, clothed in rags, with uncombed hair and rotten teeth. But these bygone craft gardeners, artists and liberal aesthetes could teach us lessons in living, loving and governing.

Archaeological excavations reveal that the Neolithic Çatalhöyük had no chieftains, police, courts, public squares, temples or centralised administrative institutions to govern the people. This was a self-regulating, egalitarian, independent, non-hierarchical society. Unlike France today, this society lived the French ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity. Marvels Edinburgh University professor Trevor Watkins, “How did a population of several thousand people live like this for over a millennium?” Çatalhöyük was so stable it survived continuously for 1,500 years. After it was abandoned, it lay undisturbed for nearly 8,000 years, providing a rich trove of artefacts and human bones that unveil intriguing secrets.

Evidence from buried remains shows people of a household were not always closely related. Says British archaeologist Ian Hodder, “They lived together like families, but not biological families.” It is reminiscent of the 1960s hippy communes in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood. Stone age homes were permeable with members moving in and out of homes that were adorned with bull horns, beautiful paintings on the walls and sculpted figurines on the hearth. Many modern communities today are post-religion. The people of Çatalhöyük were pre-religion. They lived in harmony with people and nature, without bowing before priests and gods.

The Neolithic age birthed the agricultural revolution, so one imagines these dwellers dragging heavy plows and hauling bulging sacks of grain. Says Watkins, “Çatalhöyük did not employ draft animals. Cultivation and transport was done by hand. It is better to think of this lifestyle as garden agriculture.” Keeping livestock, hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants enabled a richly diverse diet. Getting fresh, organic and locally produced food that enabled a healthy microbiome sounds like shopping in today’s trendy food boutiques.

Çatalhöyük’s residents buried their family members beneath their house. Walking over the dead is a reminder that one day, others will walk over you. After decades, they exhumed the skull, plastered and painted it and passed it around the community. Anthropologist Ian Kuijt says this two-stage death ritual symbolised keeping the dead close and then decorating and releasing the skull to join the pantheon of the community’s ancestors. Says Watkins, “These relics are like photo albums of our deceased grandparents, a way to preserve our memories. They provide a shared sense of identity and continuity.”

The sole group that enjoyed high social status was the elderly. Dietary evidence show they had the privilege of eating high-quality food. In the absence of a hierarchical governing system, “elders” shaped the social norms that maintained peace and strong bonds. Evidence suggests that elders, not damsels, inspired art.

Çatalhöyük proves that humans can build stable, complex societies where all members are equal. Says Hodder, “When I look at the world today, I am particularly concerned about our rising inequality, how we marginalise old people, and how we wreck the environment. There are other ways of living that we can learn from Çatalhöyük.”

As Twain says, there is no new idea. But it is smart to reinvent good old ideas—especially in these troubled times.

Pratap is an author and journalist.