In the 1990s, a favourite term of abuse of the sangh parivar for people like me whose first language was English and had been exposed to western education was to dismiss us as “Macaulay ki aulad (Thomas Babington Macaulay’s bastard children)”. What is underplayed is that Macaulay also predicted that British rule would not last much beyond a hundred years (he was right) and, so, by that time, Indians should be groomed to rule themselves. To this end, Macaulay devised the Indian Penal Code, which, in modified form, continues to this day. Relevant to this recall is that Macaulay’s penal code did not contain any provision for “sedition”.

That unfortunate addition was made several decades later when Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, the law member in 1870, faced with a Wahhabi insurrection, introduced into Indian jurisprudence a new “crime”—that of “sedition”—and prescribed punishment extending to life imprisonment for inciting “disaffection” against the empress and her government in India. But for over a quarter century, the “sedition” provision lay dormant. It was invoked for the first time in 1897 against Bal Gangadhar Tilak. The Narendra Modi cohort has invoked this charge 96 times in 2019 alone! Fortunately, the conviction rate is only 2 per cent. Yet, those charged have to endure frightful conditions in police or judicial custody, so that plenty of punishment is inflicted before any court conclusion is reached. Ask Stan Swamy, incarcerated in his eighties despite serious illness.

The Gandhian phase of the freedom struggle began in reaction to the Rowlatt Act of 1919, which reinforced the criminalisation of “sedition”. Gandhiji’s vow of satyagraha described the Rowlatt Bills as “unjust, subversive of the principle of liberty and justice, destructive of the elementary rights of individuals”. At his trial in 1922, Gandhiji called Section 124A “the prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen”. That is even more true of the sedition law in 2021 than it was in 1919.

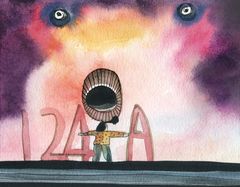

It was most unfortunate that 124A was not thrown out with the British. That was, of course, because in the chaos of partition and the recalcitrance of some of the princes, especially Hyderabad, to integrate their states into the Indian Union, and Pakistani mischief in Kashmir, sedition was very much in the air. It was, however, explicitly decided not to use “sedition” to derogate from the fundamental rights set out in the Constitution, even if it continued in criminal jurisprudence. The Punjab and Haryana High Court and the Supreme Court played a key role in reining in the executive from misusing sedition charges to settle political scores, as in the Tara Singh Gopi Chand case (1950), Kedar Nath case (1962) and Balwant Singh case (1995).

But in the last seven years of “Moditva”, the country has seen a rise of some 160 per cent in “sedition cases”, with no action being taken against those like the Union minister who incited “violence and disturbing public order” by demanding to shoot down anyone they choose to label a “traitor”. Not to worry. We have been saved. Justices U.U. Lalit and Vineet Saran, in the Vinod Dua case (2021), have reiterated that a citizen is within his rights to say or write whatever he likes about the government, provided he does not incite violence or public disorder.

It is high time Section 124A was repealed. For, as Gandhiji said, “affection cannot be manufactured” and “fullest expression” should be given to spreading “disaffection” against the government of the day in any well-ordered democracy.

Aiyar is a former Union minister and social commentator.