It is a given among our Pakistan experts that elections or no elections, the only winner is the Pakistan army for even a democratically elected civilian government is soon brought to heel by the faujis. And so, the conventional wisdom goes, should a political government go out of line, the army will bring it down. It will even hang the incumbent civilian prime minister as witness the extra-judicial murder of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

I always doubted the logic of this argument. Which is why five years ago I attributed Imran Khan’s massive win at least as much to his immense personal popularity as to the alleged backing he received from the Pakistan army. It seemed to me more as if the army were riding his wave than getting their puppet elected over the will of the people. That the army believed the Pak election of five years ago was their doing, I have no doubt. After all their media (and, to the extent it matters, our own) were proclaiming the generals as the real power behind Imran’s spectacular win. For a year or two into Imran’s regime, it seemed the standard view of Pakistan’s democracy as a farce enacted by their armed forces might indeed be true, but as the Americans moved out of Afghanistan and Pakistan’s role as a strategic American asset diminished before disappearing altogether, Imran started hewing his own path without orders from, or consultation with, the medal wearers. Differences reached such a point that Imran’s supporters actually attacked the home of the corps commander in Rawalpindi. The army moved in swiftly and had Imran’s government not only dismissed but Imran himself put in prison. His principal political opponent, Nawaz Shariff, was encouraged to return to Pakistan with immunity from further prosecution despite having been driven into forced exile on these very grounds by the same forces now welcoming him back. It seemed the army playbook was again open, and Imran would suffer persecution at the hands of those who had been pleased to back his electoral bid five years ago.

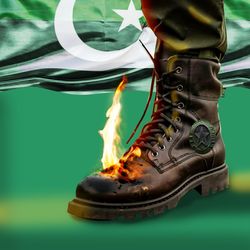

While Imran was imprisoned, effectively for life with the judiciary doing the army’s bidding, his party was dissolved, his symbol—the cricket bat which he had carried to victory for Pakistan so often—was taken away from him, and none of his supporters were permitted to stand in the February 2024 general elections except as independent candidates with individual election symbols that differed from seat to seat. They were also deprived of the time required to familiarise the electorate with their new symbols and could claim no title in their individual campaigns to their party’s name. The army sat back smugly to view the outcome of their exertions.

I happened to be in Lahore on polling day. Peace and tranquility reigned. Patient queues formed at polling booths. There were virtually no incidents of violence. It was generally believed that the populace was resigned to its traditional place as the silent spectators of manoeuvres in high places to deny them their true voice. Results were expected to flow in within hours of the closing of the polls. Instead, to everyone’s astonishment, counting went on through the night giving trends that betrayed the army’s expectations. Independents in their hordes were surging forward. The moral victory was the people’s voice. Imran-backed independents scored a century. Nawaz was left trailing at 30 per cent less seats; Zardari-Bhutto got less than half Imran’s score. The real loser was the army.

A government without Imran’s party may indeed be formed, but February 8, 2024, will be chalked up as the historic day on which the people of Pakistan defeated their army.

Aiyar is a former Union minister and social commentator.