Soli Sorabjee, who was attorney general during the six years of Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s prime ministership (1998-2004), had oneregret. The eminent jurist could not persuade Vajpayee or his hardliner home minister L.K. Advani to notify an amendment to the Constitution which both had voted for in 1978. It was an amendment aimed at improving civil liberties, post Emergency, by reducing the period of preventive detention from three to two months.

The amendment was introduced by the Janata government of Morarji Desai as a reaction to the muzzling of the Constitution by Indira Gandhi’s Emergency-era Parliament. While president Neelam Sanjiva Reddy notified amendments to 49 Acts and schedules—which repealed many changes brought by the infamous 1976 amendments—the Janata government, which was already wobbling, postponed notifying the preventive detention amendment under Article 22. Sorabjee, as solicitor general in 1978, had helped law minister Shanti Bhushan and attorney general S.V. Gupte to draft the omnibus amendments to ensure that “people themselves [are] an effective voice in determining the form of government under which they are to live”.

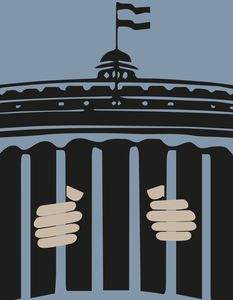

In early 1980, Indira Gandhi was back in power and she did not notify the law, as the home ministry argued that preventive detention, without review by an advisory board, should be valid for three months. Successive home ministers of different political persuasions also held this view. Even prime ministers who were themselves victims of preventive detention—Chandra Shekhar, H.D. Deve Gowda, Vajpayee and Narendra Modi—shied away from giving relief. Consequently, central agencies and state police have powers to detain persons for three months without explanation, and later for a year or more, based on the approval of an advisory board headed by a retired High Court judge.

Civil rights activists have argued that the protection given by Article 22 of the Constitution, that every Indian who faces arrest should be produced before a magistrate within 24 hours, has been nullified by this provision. And, it has been used against all kind of persons—alleged Maoists, stone-pelters, mobsters and even ordinary thieves. Recently, the Supreme Court was surprised to hear the petition by a detainee in Telangana—the member of a gang accused of lifting saris from malls in Hyderabad. The apex court wondered why he was not produced before a magistrate, who can remand him to prison until the charge-sheet is filed. The court threatened to pass orders, but the Telangana government filed a FIR and produced the alleged sari-thief before a magistrate.

Another shocking case is the detention of Sanjiv Bhatt, a former IPS officer of the state and a critic of the prime minister, by the Gujarat Police. Bhatt is under preventive detention and the government is not giving him the causes for his detention. Article 22 provides for officials not to give reason for detention to protect “public interest”.

Even though there are human rights commissions at the national and state levels, relief has been patchy for those who are under preventive detention. Police and government lawyers use “sealed covers” to give information to the commissions and courts, so that the detainees and their lawyers would not know the causes for detention. Even though Modi and his key ministers like Arun Jaitley and Ravi Shankar Prasad criticise the onslaught on civil rights during the Emergency, Prasad told Lok Sabha that the government is not keen on notifying the preventive detention amendment, even though the Parliament approved it 40 years ago.

sachi@theweek.in