We are into what has come to be known as the ‘lit fest’ season. From Delhi to Bhopal, Chennai to Jaipur, Mumbai to Hyderabad and increasingly in newer centres, a kind of celebratory circus gathers around writers, ‘public intellectuals’ and media celebrities. It is, of course, heartening to see lots of young people at these literary festivals and one hopes they are all book readers. I say “hopes” because many in the audience are not. The growing popularity of book fairs and literary festivals is only slowly translating into book buying and reading.

When ill-informed questions about my books have been directed at me at such lit fests, I have sometimes had to ask the questioner if he has, in fact, read the book. More often than not the reply tends to be, “No, but I plan to.” The proliferation and growing popularity of lit fests has meant that politicians, publicists and Page 3 celebs have all jumped on to the platform. Speakers are expected to spar and joust like gladiators, stabbing each other with smart one-liners, and often entertain more than enlighten. How many at lit fests have actually read the books of authors they wish to hear, question and criticise?

It is now a wider malaise, thanks to social media. Consider the number of critics of a writer like Ramachandra Guha on Twitter. How many of them would have actually read his voluminous, well-written books? I would imagine very, very few. The social media view of an author’s writings is shaped, at best, by his newspaper columns or television appearances and, at worst, is manufactured by partisan critics.

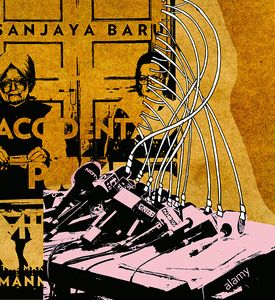

Four years after the publication of my book, The Accidental Prime Minister: The Making and Unmaking of Manmohan Singh, I am still confronted by opinions about the book based on comments in the media. Every time I am asked an ill-informed question or face a baseless comment, my gentle reproach has been to urge the interlocutor to read the book, in full, cover to cover. Those who have read the book appreciate the fact that 80 per cent of it constitutes the best available defence in print, even as of now, of the Manmohan Singh prime ministership. The book would have read like a hagiography, an unrelenting paean to the former prime minister, if it had not also contained the 20 per cent of criticism.

In a new afterword, published in the book’s latest edition, I have mentioned the fact that I had alerted the PM and his office to the fact that while the book is, by and large, a defence of Singh’s tenure, the media would focus on the critical comments. That is what happened. The PMO’s knee-jerk response and the media’s focus on the book’s controversial parts, rather than the totality of a complex argument, have shaped thinking about the book both among its critics and most admirers! Now with the book being adapted into a movie, chances are that a larger body of opinion about the book is going to be shaped by what the movie’s producers have claimed to be a ‘fictionalised’ dramatisation of the book. A pity.

My experience with the critics of my book is far from unique. So many authors, especially those who have written on history, politics and religion, have found themselves at the receiving end of ill-informed public criticism, especially on social media, where the critics have clearly not read the book. Controversy may help sales, but it prevents a reasonable view being taken of a nuanced argument.

Baru is an economist and a writer. He was adviser to former prime minister Manmohan Singh.