Way back in the 1960s, when my generation was in its teens, long before any economist wrote about globalisation, Marshall McLuhan wrote a bestseller—The Gutenberg Galaxy—and coined the term ‘global village’ that made waves around the world. The book is full of quotable quotes about modern media, advertising, communication, politics, technology and so on. The most persuasive and lasting thought he left behind among his readers was the idea of the world as a village. That time and space had been shrunk by technology.

It was a couple of decades after McLuhan’s book was published that the word ‘globalisation’ captured the imagination of most people as they began to travel more easily and buy goods in their neighbourhood shop manufactured thousands of miles away. Television, as McLuhan reminded us, had brought the world into our living room. “Everybody experiences far more than he understands. Yet it is experience, rather than understanding, that influences behaviour,” he wrote. Television had brought experience closer home, without the required understanding of that experience. McLuhan believed that the Vietnam war was lost in “the living rooms of America—not on the battlefields of Vietnam”.

As we sit in our living rooms and experience the communal hatred in the dirty, crowded streets of the nation’s capital; the fear of coronavirus from Wuhan to Paris and Tehran to Bangkok; the propaganda about citizenship and migration in the streets of Kolkata and Paris; the talk of fair and unfair trade in the election rallies of the world’s most powerful nation, we hear the drumbeats of the global village.

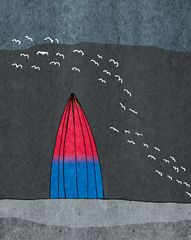

The village drummer brought people together to inform them, warn them, alert them just as modern media does. The parallel ends there. The village drummer knew that the destiny of every villager was linked to that of another. His drumbeats were for all. Does modern media know that? Does television today beat the drum for all? When a virus engulfs a village, all are threatened. How stupid of anyone to imagine that one is safe while neighbours die of a spreading virus.

The metaphor of the global village was meant to remind us of our shared destiny. Not just of those within a single village but of those in villages around, and those that inhabit the space between villages. The drumbeats of one village were heard in the next and so the message went forth.

To imagine that one can have free flow of the good things of life through trade and travel, but keep what one does not like out with a wall in between is naïve, to say the least. The information on climate change only reinforces ancient knowledge that nature recognises no borders. Indeed, till the middle of the 20th century, humans, too, had no particular regard for borders. The history of mankind has been the history of movement of people, sometimes in response to the challenge posed by nature and sometimes in response to the threat posed by fellow humans.

Just as the clouds above move freely across borders, so do animals below and so did humans. For how long can mere governments prevent the free movement of people when nature, the search for life and livelihood, for security and safety push people to move? When governments are unable to prevent a virus from crossing borders, how long can they prevent ideas from doing so? When big business wants free movement of capital and goods, how long can it prevent the free movement of people? Such are the questions that the drummers of the global village raise and we cannot remain deaf to their beats.

Baru is an economist and a writer. He was adviser to former prime minister Manmohan Singh.