On my 12th birthday, my parents decided I was old enough for pocket money. Two crisp five-rupee notes were deemed sufficient for a month’s expenses—and they were. I clearly remember treating my friends to colas and burgers in the school canteen with just one of them, eliciting admiring cries of ‘whoa, big spender!’ from all present.

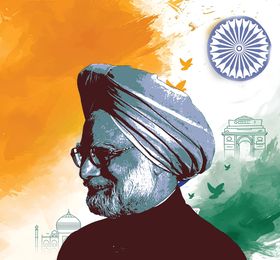

Perhaps, because we had no television, mobile phones, or video games back then, I spent a lot of time smoothening down and gloating over my pista green and pale-orange fivers. I dug the denseness of their texture. I found the curly whorliness of ‘five rupees’ written in all the Indian languages mysterious and romantic; the picture of a man tilling a tractor against a rising sun reminded me of my grandfather’s village in Haryana; the solemnity of ‘I promise to pay the bearer the sum of five rupees’ written in English and Hindi gave me actual goosebumps, and I loved the fact that making all this sound tremendously official and trustworthy was a neatly scrawled signature in dark ink—‘Manmohan Singh’.

Everybody describes Singh as ‘mild-mannered’, ‘self-effacing’ and ‘meek’, but how does one chart a journey from the small towns of Punjab, where he was educated in Urdu and Gurmukhi, to Cambridge and Oxford, the Delhi School of Economics and the University Grants Commission, serving as governor of the Reserve Bank of India, and ultimately ending his career as prime minister of India, without either strength or determination? The answer is that you can’t. Singh’s strength and his determination lay in his intellect. But, in an era where we applaud ‘diamonds-in-the-rough’, disdain Nobel laureates and Cannes winners, and worship ‘street-smarts’, the merits of actual smarts naturally pass us by.

I am not romanticising Singh. The man who appointed him to his first political post as finance minister—prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao—deserves equal credit for picking the right man for the right job, and giving him free rein. Rao displayed a chill and a lack of insecurity that is rare to find nowadays, or indeed at any time. And some would say, he paid the price for it.

I guess what I am really mourning, while reflecting on Singh, is the passing of a time when our leaders genuinely respected and empowered our intellectuals to take on a larger role in public policy—from aerospace scientists like A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, to brilliant strategists like Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, to uncompromising bureaucrats like T.N. Seshan.

To make the point more stark, Singh and Raghuram Rajan were both governors of the RBI, but the contrast in the manner they were treated by the regime in power could not be greater! I am not saying that there is something inherently superior about people who are more qualified than you, but, similarly, there is nothing inherently superior about being unqualified and ill-informed. Why not take counsel from somebody who has devoted decades to become an expert in a particular field, instead of (to cite an infamous case) appoint a B-grade TV actor to head India’s premier film and television institute?

Strangely enough, those who disdain actual intellectuals (like Romila Thapar, say) and claim to revere underdogs with ‘real-life learning’ are the first to speak up against caste-based reservations that benefit the genuinely deprived! Union Home Minister Amit Shah calling Dr B.R. Ambedkar—a scholar alumnus of Columbia University and the London School of Economics, founding father of our Constitution, and lifelong champion of dalit rights—a ‘fashion’ is a classic example of this sort of cultivated contempt.

Intellect is not fashion. It is a rock-solid merit. One that our nation urgently needs to value.

editor@theweek.in