Kumar (name changed) is a 16-year-old promising hurdler. He has been training at ASF, my sports foundation in Coorg, for the past two years. Now in his 10th grade, he has decided to drop out of sports to focus on pursuing a professional academic degree, even though ASF looks after athletes till they finish college. Kumar’s is the stereotypical story of what is happening in our country, especially in urban areas. Parents are not keen on letting their children pursue sport because it does not ensure a secure future.

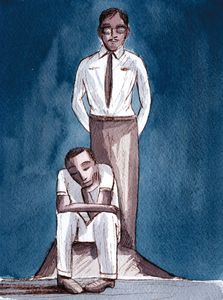

If sportsmen are not academically inclined, and if they hail from low- to middle-income households, sports could be an opportunity to break their limiting conditions. But, it provides no guarantee of a secure future. So, many from such backgrounds choose to do a BA or BCom, which they see as a safer option. Unfortunately, most of these youngsters give up sports.

Those who have the courage to follow their interest, they do so against all odds. And, only a handful succeed. Thankfully, for such top performers, the safety net that our PSUs, governmental bodies and a handful of corporates have provided has been a godsend. Whatever sporting successes that our country has achieved, cricket included, is mainly because of the safety net of employment these organisations provided to top athletes. Who can forget the hockey teams of Indian Airlines and Air India that produced many greats? My husband, Datha, who represented India juniors in hockey, played for Air India. Railways has been one of the most proactive employers supporting sport; its most famous employee being M.S. Dhoni.

As for me, I was offered a job by Vijaya Bank right after 12th grade. It was a huge relief for my parents and me, as it meant I could focus on my athletics career and not worry about working to make ends meet. It made an enormous difference, mentally, emotionally and economically. Recently, Harmanpreet Kaur, India’s intrepid women’s T20 captain, was given a job by Punjab Police.

Yet, for every Harmanpreet Kaur there are a thousand others waiting to make their mark. What happens to these athletes? What is their safety net? It is largely chance that an athlete of meagre means makes it to the top.

There are three distinct phases to an athlete’s career. The first is the struggle phase to establish oneself at a national level. The next phase is training to be an international athlete and the final phase is post-retirement from sports. All these require a safety net relevant to that phase. Much of the support from PSUs, other organisations as well as the emerging competitive super leagues is in the second phase. However, it is in the first phase that one requires clarity about a secure future, to even think of someone wanting to take up sport. Education that provides career options is crucial, should the athlete not make it beyond phase one. Post-retirement, there needs to be a concerted effort to retool the athlete for a secure, stable life.

Today, for-profit organisations define the economy and they must play a decisive role in providing such a safety net. Two per cent of their profits is mandated to be spent on developing their communities, and it is only logical that sports be included in it. They can do so by ensuring that the education needs of athletes are met right through school and college and create programmes for retooling and absorption of athletes post-retirement. These small steps can have a substantial impact in developing our sporting potential.

Ashwini Nachappa is a former athlete