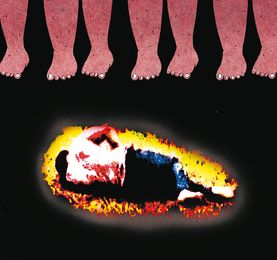

We should all be sickened by the horrific image of Tabrez Ansari, the 24-year-old Muslim man who was lynched to death in Jharkhand by a mob that accused him of theft and forced him to chant ‘Jai Shri Ram’. And, there has been the usual eruption of outrage and condemnation, including by the prime minister in Parliament.

It would be tempting and comforting to locate these assaults, most of which have been against dalits and Muslims, in the larger framework of a law and order problem. The truth, however, is less palatable. I fear that despite the fact that all the right things are said by all of us, every time a murderous mob targets a hapless innocent, we are reaching that dangerous point of numbness. A point where Mohammed Akhlaq, Pehlu Khan and Ansari are becoming blurry statistics and yesterday’s headlines instead of flesh and blood men with families they leave behind.

We say we are angry. But are we really? Because if we were—like during the gang rape of Nirbhaya, or more recently the Kathua rape of a little child—we would have been out on the streets, marching, protesting and demanding change. Instead of shaking us out of our passive condemnation, every case of lynching only seems to lull us and blunt our edges. When will we say enough is enough?

Whether we like it or not there is an enabling environment being created that emboldens the murderers who lynch. Recently I met Mohammed Danish, Akhlaq’s son, who left his village in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh, ever since his father was beaten to death over rumours of storing beef at home. Danish’s brother is an Air Force personnel who had this to say of India, even after his father was murdered: “saare jahan se acha, Hindustan hamara”. Danish, whose skull was broken open by the same mob that killed his father, showed no signs of bitterness. Instead, he spoke sadly of having had to relocate from his home, his sense of loss at the fact that his Hindu friends no longer speak to him and his hope for returning home one day.

What justice can we offer Danish when he sees the Uttar Pradesh chief minister address a rally where the Dadri-lynching accused sits in comfortable attendance, in the front rows of the event? Or, when a senior leader of the BJP garlands men implicated in a lynching case? Or, when every public and media discussion about lynching ends up in the worst sort of whataboutery and competitive point-scoring? What hope for justice are we offering to the victims of lynching? Think about the fact that there has not been visible justice in any of the high profile, headline-grabbing lynching cases over the last few years.

The Narendra Modi government is among the most powerful in India in recent memory. One of its distinctive features is the strongmen it is helmed by—both the prime minister and the Home Minister Amit Shah. They have won elections on the alpha-male positioning of the prime minister. If ever there was a moment to display strength, even brute strength, this moment calls for that.

The prime minister must take the lead in cracking down on those who dare to kill, and believe they have impunity.

editor@theweek.in