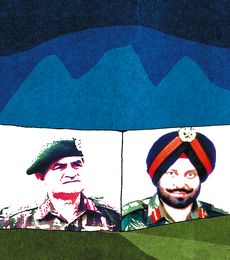

It is exactly 20 years since the Indian military took back our territory in Kargil, pushing back the Pakistan army’s soldiers, in one of the most extraordinary, valiant demonstrations of mountain warfare that the country has ever seen. As a journalist who had the privilege of reporting the Kargil conflict from the frontline, I can testify to the raw courage of young men still in their twenties, putting aside fear, vulnerability and a sense of impending death, as they marched up jagged rocks, in sub-zero temperatures, often without snow boots or night-vision devices. “We will fight with what we have,” said then Army chief General V.P. Malik, and indeed they did.

Kargil is often called India’s first televised war, even though not many know that we reported it without the technology we take for granted today. We neither had live broadcast vans or satellite links, nor did we have mobile phones. Footage travelled back to our newsrooms in the same helicopters that ferried the body bags of our soldiers. Several days could pass between information from the frontline actually making it your television screen. Yet, despite the archaic media infrastructure, it was an inflection point in establishing an emotional connect between the soldier and the civilian.

Two decades on, in this age of political nationalism, while we all say we revere our military, we must ask ourselves: Did we really learn some of the finer life lessons that the Kargil War taught us?

Apart from the breathtaking bravery of our jawans and officers, and the swashbuckling charisma of men like Captain Vikram Batra—who told me “yeh dil maange more”, when I asked him if he was scared—Kargil gave us an insight into a soldier’s code. It taught us that a genuine nationalist plays by the rules; he does not deny dignity even to his adversary.

One of the finest illustrations of this higher code was the decision by General Malik that the last rites of Pakistani soldiers killed in action would be performed by Indian soldiers. This was necessitated by the fact that Pakistan initially refused to take back the bodies of its men, because it was unwilling to concede that they were regulars of its military.

Recently, General Malik told me how, a few months after the war was over, at the request of the grandfather of one of the Pakistani soldiers killed, he even had the young man’s body exhumed and handed over to his family with full military honours. What made you do this, I asked him, especially in that environment when Indians were furious at how the Pakistanis had tortured Captain Saurabh Kalia in custody. “This is our tradition,” he said. “We know no other way.”

We also know the extraordinary story of Brigadier M.P.S. Bajwa who spearheaded the recapture of Tiger Hill, without which the Kargil conflict could not have been won by India. As a brigade commander, he was able to secure a Param Vir Chakra, a Mahavir Chakra and multiple other gallantry awards for his troops. But he also made sure that Captain Karnal Sher Khan of Pakistan’s Northern Light Infantry was able to posthumously win his country’s highest honour, the Nishan-e-Haider. Once the captain was killed in action and Tiger Hill was taken back, Brigadier Bajwa made sure he wrote a letter commending the Pakistani captain for how bravely he fought and placed the letter in his pocket, before the body went across the border.

In an age when television anchors think they are soldiers simply by shouting about nationalism and at a time when patriotism has been reduced to a hashtag, this is what being brave is truly about. To honour the code. And, to do it with generosity and compassion.

editor@theweek.in