Often, there will be an amusing story about a malkhana (evidence room). For example, three years ago, there was a report about 1,000 litres of liquor that went missing from the malkhana of a police station in Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh. The police said a “gang” of rats drank up the liquor.

More recently, in 2021, firearms, drugs, bombs, cash and ornaments went missing from a malkhana in Katni, Madhya Pradesh. In this case, the malkhana was not in a police station; it had been shifted to the premises of the district court. Malkhana literally means a storehouse and they are in bad shape. Gangs of mice and men make stuff deliberately vanish. Sometimes, valuables are inadvertently lost, or misplaced.

A couple of years ago, cash went missing from a malkhana in Chandigarh. No, it had not been stolen. It had simply been misplaced when the police station was being renovated, and no one knew where the cash had been kept. Eventually, it was found. When a case is going on, such articles are defined as “case property” under Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC). Courts will decide what needs to be done with such property, during trial and after trial.

How many people remember Raja Man Singh’s (he was elected as MLA several times) death in a police encounter in 1985? He was killed in Bharatpur, but the case was subsequently transferred to Mathura, and the guilty policemen were sentenced in 2020, after a mere 35 years. This is not an aberration. More than 75 criminal cases from 1950-s are still pending.

Should evidence, in the form of case property, sit in a malkhana? CrPC does not require that and the Supreme Court (in 2002) has ruled, “It ought not to be retained in the custody of the court or of the police for any time longer than what is absolutely necessary.” However, it is absolutely necessary to retain it until evidence has been recorded and that is also subject to inordinate delays.

The default option should be that a proper description (panchnama) of case property should suffice as evidence before courts. Why does actual case property have to be physically produced? It does not have to be, and CrPC and Supreme Court judgements have underlined this.

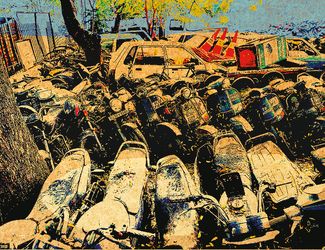

Case property also includes vehicles and the court mentioned these too in that 2002 judgement: “It is of no use to keep seized vehicles at the police stations for a long period.” Obviously, the Supreme Court did not say this—but vehicles, and their parts, have a reputation of vanishing, or getting stolen, from police stations. A police station in Pune is reportedly struggling because of the thousands of vehicles that are piling up. There is no space inside, and vehicles spill over and crowd the roads outside. Sure, under the law, these vehicles can be auctioned. But state government has to appoint an auctioneer and there are delays there.

National Police Mission has a report on malkhana management and there have been reports of e-malkhanas in some states, digitising the inventory. Sometimes, this seems to be ad hoc, that is, not for all police stations. Andhra Pradesh has a standard operating procedure for all police stations and Kerala stores all seized vehicles in a centralised yard. While such initiatives are welcome and makes management easier, does the inventory have to be physically stored and if so, where?

As an example, why cannot cash and jewellery be kept in bank lockers? That is possible, but permission of the court is needed to do that. There lies the rub. Getting permission takes time and it is not necessarily faster than recording of evidence. It seems to me that valuables should be moved to bank lockers by default.

Bibek Debroy is the chairman of the Economic Advisory Council to the prime minister.