GUEST COLUMN

On March 25, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg ran full-page advertisements in nine leading British and US newspapers, admitting data privacy breach on the social networking platform. Facebook policies had enabled a Cambridge researcher to harvest data of more than 50 million Americans through a psychological test of just 2.7 lakh Facebook users, who had consented for the same. He shared it with (sold it to) Cambridge Analytica (CA, a political consultancy), without authorisation.

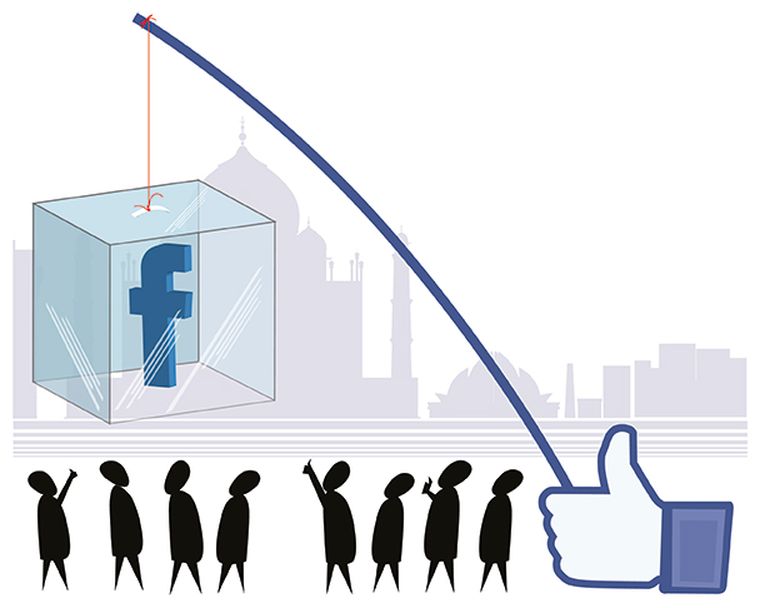

Facebook collects personal information from users, and generates insights into their behaviour by analysing their ‘likes’, interests, relationships, political and religious views, social views, locations visited, countries and regions. It categorises users into ‘like-minded’ groups and ‘personality types’—target audiences for advertisers.

Facebook makes this platform available to hundreds of thousands of app developers in its quest to make it attractive to more and more people, which, in turn, makes it useful to advertisers and other organisations, such as political parties. No wonder, it is home to two billion global citizens, who are residing in different countries, but receive targeted messages, which are aimed at changing different aspects of their behaviour, including making them change governments through elections and/or mass movements.

Prior to the newspaper ads, Zuckerberg, in his post on Facebook on March 23, admitted that its policies were responsible for “a breach of trust between FB and the people who share their data with us and expect us to protect it.” Is it merely the misuse of data or data privacy policies that is at the heart of the problem? Why has this problem assumed such proportions when data protection and privacy principles have been around since 1974? The privacy principles are nearly universal: data collection for a stated purpose with consent of data subject, purpose limitation, accuracy and quality of data, cross-border data flows, data security, legitimate interests and accountability of data controller. User to be informed of data privacy policies by the data controller so that he can take informed decision on sharing his data.

What has changed in cyberspace over the last decade that warrants a fresh look at data privacy? It is the social media platforms, accessible over broadband from a variety of devices, with interactive participation of data subjects through myriad apps, that have led to creation of innumerable communities on the internet. The race is to have apps for niche areas such as entertainment, shopping, travel and food. Big companies offer their platforms as gateways to the internet for data subjects to reach out to these apps—they provide the authorisation infrastructure.

It is these apps that collect users’ information for better services, convenience and delight! It was such an app which was using Facebook to reach users for the personality quiz. It harvested data of users, their friends, and friends of friends, since Facebook allowed that in its earlier version. For the latter group, it was without their express consent!

The scene gets fuzzier when one talks of fake likes and other news that gets pushed on to walls of unsuspecting users by bots and artificial intelligence (AI) apps that have been created by vested interests to influence the thinking of ‘like-minded’ groups identified for a specific purpose. In the political area, this could be to arouse the feelings or to cause depression/pessimism to drive a particular outcome. The jury is still out on the impact that Cambridge Analytica had on the Trump campaign—whether it did make Afro-Americans depressed enough to not go out to vote because of the perceived futility of voting, or other groups of Americans to vote in large numbers to make “America Great Again”. The picture got muddier because of the suspected meddling by Russians in buying fake advertisements to drive a specific view.

In India, too, the apps today include those of political parties. Witness the war of words between the Congress and the BJP on what personal information of users are they collecting. Are they collecting too much information than they should for sending targeted messages? Are they sending data to servers abroad? Are they following the privacy policy that they have declared on their websites? Christopher Wylie, the CA whistleblower, has confirmed in his testimony to the British parliament on March 27 that CA did provide services to the Congress party and others in various regions. What impact did it have is a matter of detailed study. But, is it illegal to hire consultants? Perhaps not!

State of data privacy of mobile apps in India—a study of 100 apps developed in India for local audiences—carried out by Arrka in December 2017 analysed the kind of personal information collected, shared with (or sold to) third parties, and the kind of tracking that the users are subject to. The study looked at mobile apps with dangerous permissions that allow sharing of personal information that is sensitive (as categorised by Android) as this enables tracking of the subject, building his profile. These include: calendar, camera, contacts, location, microphone, phone, sensor, sms, and storage. While 40 apps have 10 dangerous permissions, 31 have more than 10; with an average of 7.9 per app. Many of the mobile apps have third party software development kits embedded in them. These SDKs may belong to advertisers, analytics providers, or some specialised partners of the app provider for providing some specialised feature or functionality.

Clearly, there is scope to improve policies. But, should there be strong regulation to monitor the implementation of policies? There should be no knee-jerk reaction in favour of a strong data protection authority empowered to monitor and control. Such monitoring will promote an inspector raj that will more likely impede the digital economy, with no positive impact on privacy enhancement. India needs a proactive, but light-touch regulation with industry SROs working with the data protection authority in a co-regulatory model under the proposed DP Act.

Finally, CA using the harvested data of potential voters has violated no laws in India. It is immaterial whether the BJP or the Congress has used its services to micro-target advertisements based on the psychological profiles of potential voters. Justice B.N. Srikrishna, in an interview, laid to rest the threat issued by the law and IT minister to Facebook—of summoning Zuckerberg if there is any meddling in Indian elections. Blocking access to CA (done by the government) is no solution, nor is banning of companies, as per Justice Srikrishna.

What we do need is a data protection law that incorporates the learnings from the US, EU, UK, OECD and APEC privacy laws/frameworks; and it takes into account all facets of the digital economy unique to India in its growth story at this time when we are poised to become a trillion dollar IT economy—a whole new privacy ecosystem with minimum bureaucracy, and minimum government control. No knee-jerk reaction, please. That would be counterproductive. Let the Srikrishna Data Protection Committee submit its report.

Bajaj is founder CEO of Data Security Council of India and founder director of CERT-In.