In childhood, everyone is in awe of some aged relative—sometimes for reasons as corny as their remarkable capacity for belching or sneezing or snoring or passing wind. As children, we sometimes found the foibles of grownups delightful or amusing, and sometimes even disgusting. But all the quirky grownups and their kinks were memorable! I have had my share of idiosyncratic relatives, but the one who was outstandingly peculiar was a granduncle, whom everyone called ‘Baba’. The whole family has memories of his many eccentricities but, above all, he is remembered for what came to be called the ‘Great Shaving Tamasha!’

Baba had a tough beard and he managed to grow the most bristly fuzz in just a day. In spite of—or maybe because of—this, he never shaved on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Saturdays and Sundays were in any case days of rest. The grand show was therefore mercifully confined to just thrice a week. The tamasha used to start early on the earmarked days, and the whole household remained in a tizzy for two hours or more.

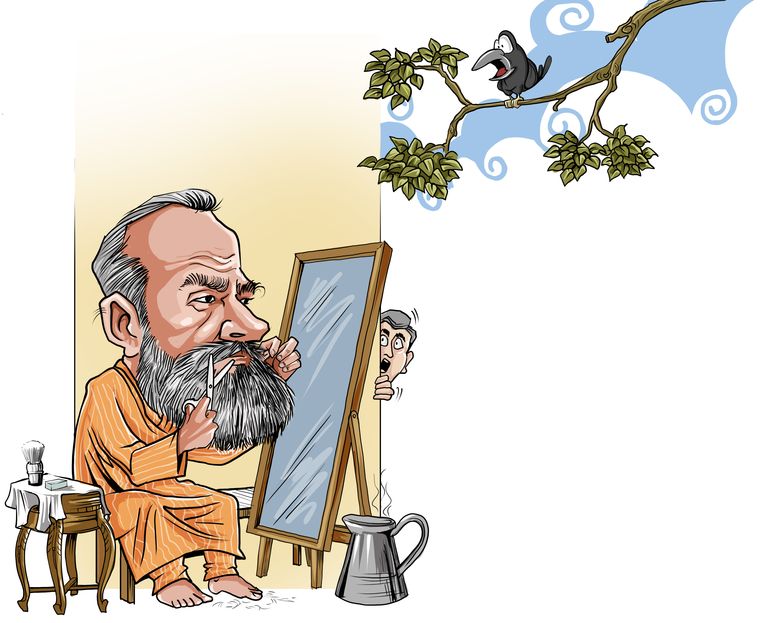

Baba first marshalled the equipment and paraphernalia required for the ritual. A cot would be placed in the courtyard, with an ancient wooden stool beside it. Baba would then carefully spread a snow white towel on the stool and lay upon it a variety of instruments and unguents, including a shaving stick, a cake of alum, a shaving brush made from the hair of some exotic animal, a cutthroat razor and a leather strop, a safety razor and a glass and canvas contraption to sharpen razor blades, trimming scissors and, incongruously, a pot of ‘Afghan Snow’—which was a kind of moisturising cream used almost exclusively by ladies.

The last to be placed on the table was a folding mirror. With the forgetfulness of an old man, each time he placed the mirror on the stool he would inform all and sundry that his father had bought it in Paris at the end of the great war. No one dared ask which war, because, as everyone knows, there has been only one great war.

Baba would then holler for hot water, which would be brought to him posthaste in a jug by some minion. He would proceed to soak the brush for a good half an hour and order anyone passing by to get a fresh tumbler of hot water to soften his beard. All this while, he would sharpen the cutthroat on the strop, till it gleamed in the morning sun. By the time he was ready to shave, the water would have run cold again, so shouts for ‘Bittoo’ or ‘Kaddoo’ or ‘Chhotu’ would ring out, as he imperiously summoned one of the innumerable brats of the family.

An unnatural hush would descend on the house when the actual shaving ceremony was about to commence. Everything had to come to a stop so that Baba’s attention was not diverted as he started slathering his face with the ‘Erasmic’ shaving stick. Even the raucous crows that perched on the courtyard wall and incessantly cawed for attention fell silent and stared at Baba—tilting their heads first this way and then that. The battle to get rid of the stubble would follow; with Baba giving his full attention to the angle of his cutthroat razor so that he did not nick himself. If he did, which was often, he gave vent to a string of oaths, curses and blasphemies that made the womenfolk blush.

The brats in the home were too young to fully comprehend the profanities, but they were quick to pick up the words and tried saying them aloud when they were certain no grownups were within listening distance.

After the ritual was completed, Baba would finally leave for office and the family would heave a sigh of collective relief. Everyone’s blood pressure would return to normal; at least till the next shaving hoopla.

In a way, Baba was indeed the last of the Mohicans; the last of the imperious paternalistic generation. A generation whose timid descendants have been great disappointments—devoid of colour and imagination and bereft of any angularities and idiosyncrasies. My dad and uncles had no sense of drama and they shaved quietly, almost in a furtive hurry. If they nicked themselves, there was no fuss. They simply dabbed some aftershave, stuck a piece of tissue on the cut and meekly went off to work.

I am still more ordinary. I have greyed but I have no fuzz to show even if I don’t shave for two days. Moreover, I use an electric shaver—sans soap, sans alum, sans drama. My entertainment quotient is nil and my grandchildren are deprived of the extravaganzas which enriched my childhood. I suspect I am an utter failure—after all, what is a grandfather good for if he can’t even create memories for his grandchildren?

K.C. Verma is former chief of R&AW. kcverma345@gmail.com