A year or so ago, if anyone had told me that Tommy Hilfiger would have stolen the show at New York’s Met Gala, I would have laughed. But it seems the end of giant luxury labels is upon us even before we expected it. The American ready-to-wear designer Tommy Hilfiger seems to have created the maximum media buzz at the 2024 Met Gala, according to several data analytics firms.

Even though big names such as Loewe, Balmain, Armani, Chanel and Maison Margiela made their statements here, almost equally prominent were mall favourites like H&M, Hilfiger and even Gap. Yes, on celebrities.

How did luxury labels fall out of favour with celebrities? Simply because they did so with consumers first. Even though many European luxury brands are showing an uptick in their numbers, their consumers are mostly the new rich or the aspirational rich. These don’t bring much cred to the brand, they mitigate the label’s snob appeal instead.

An interesting opinion piece appeared on industry bible businessoffashion.com last week, by guest writer and StyleZeitgeist editor Eugene Rabkin, titled ‘How Long Will The Luxury Myth Last?’ Rabkin says the Great Recession of the late 2000s threw luxury brands a curve ball, but they were saved by just one market: China. The country generated enough and more shoppers to sustain the industry at large. “In 2000, the world had 15 million millionaires; by 2022 that number had roughly quadrupled to 60 million,” she writes. “Through glittering megastores, celebrity-fuelled campaigns and shrewd strategies like category segregation that confined image-driving products such as evening dresses to high price ranges, ensuring they were unattainable to most, while pitching others, such as beauty, at price points for the masses, luxury brands have long managed to sell ‘exclusive’ goods by the millions.”

Once brands realised their marketing had worked, they began to sell high-street items like sneakers and sweatshirts at luxury prices. They were lapped up. Volumes increased and quality fell. Rabkin says “the post-pandemic exuberance is over and new customers are pulling back thanks to high interest rates and costs of living. Furthermore, China has stopped producing millionaires”.

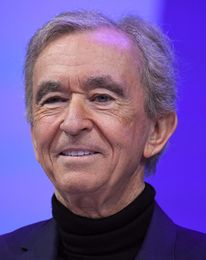

India is hardly stepping in for China. Women’s Wear Daily magazine quotes a Barclays report that states, “Comments from brands have been very bearish so far, with LVMH CEO Bernard Arnault stating in 2023 that India is not a country where they can have a network of luxury shops due to a high level of income disparity and too low a level of GDP per capita.” Homegrown luxury labels are now taking over China and India.

Several industry watchers such as myself and The New York Times have questioned the inexplicable rise in prices of luxury labels. Data company EDITED has noted that luxury prices have been raised by 25 per cent in the last five years alone. Rabkin believes this has pushed customers away, even the rich, because “nobody likes to be taken for a ride”, she writes.

Another interesting development is that succession in mega companies is failing. Arnaud Lagardere, the son of French duty-free behemoth Lagardere’s founder Jean-Luc, has been forced to resign after accusations of false information, vote buying and misuse of corporate assets. All of France’s big wealth creators are in their 70s and 80s—Arnault is 75, Vincent Bollore of Vivendi media is 72, and Francois Pinault of Kering is 87. All of them are placing their children and grandchildren on their boards (Pinault’s grandson, also Francois, now heads Christie’s auction house).

But a new world demands a new order.