I really can’t imagine why more of us don’t throng Goa each December for the Serendipity Arts Festival alone. The festival, in its ninth year now, has the entire Panjim town celebrating. Multiple venues are tastefully decorated for what has come to be South Asia’s biggest multidisciplinary arts festival. Sunil Munjal’s vision, along with a happy partner in the state government, has seen public work buildings (the old accounts building, Goa Medical College, Fontainhas, and others) restored and painted vividly to celebrate Goa even as spectators partake of arts, music, culinary arts, theatre, fashion and crafts. Next year, the festival goes international with its first-ever showcase in Birmingham, UK.

One of the most inventive ideas here in Goa was an immersive visual arts room created by Himanshu Shani of 11.11 fashion label. Shani has long been a researcher and an advocate of natural clothing—right from its farming processes and rain-water harvesting practices to hand-spinning, hand-looming and hand-stitching. His clothes are rich with heritage and rural savoir faire. They have a small cult of followers across the world, right from Japanese savants to Mira Nair in New York and Nikhil Kamath (a vocal interested investor) in India. Shani keeps his head down and focuses on research and development, instead of celebrating his small success to achieve bigger rewards.

The immersive room asks visitors to wear plastic coverings first, and then a raw denim covering over their shoes. I was lucky to have Shani assist me with mine; I count among his first clients and forever fans.

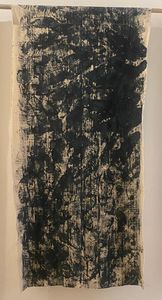

Visitors then walk into the large room after crossing a little indigo paste pool. Our footprints leave deep blue marks on the floor, carpeted with white handloom fabric. These carpets will then be pulled up and hung to dry like art works at the festival, and Shani says he will be creating some products out of them. All of them will have our footprints on them, and we will thus be a part of his production process.

As we walk through, the process of how indigo is created from the indigofera plant to its eventual dying of yarn is displayed. (The handwritten notes of chalk are by another famous fashion designer, Aneeth Arora of Pero.) Indigo is trapped in the leaves of the native plant. It is extracted before the plant starts flowering as a seed can cultivate just two or three times. The leaf is soaked in water, a blue pigment emerges, which is then dehydrated into cake. This has organisms in it, and 50 per cent intensity indigotin. The cake is added to vats, along with dates (or honey) for glucose and alum or imli to make it alkaline. This vat is now a living being, it can last for centuries. Shani’s are 12-14 years old. You dip in yarn to pick up a yellow colour, which then turns green and finally blue with oxidation. The blue changes with the intensity of indigotin; it’s different in summer from winter and differs when dyed in Gujarat from in Delhi.

Shani learned biodynamic farming from David Hogg of Araku coffee. “When you respect the earth, it gives you what you earn from it,” Shani avers. Biodynamic farming also follows the lunar calendar and particular water cycles, so cosmology is part of it, too.

Shani says he is now working on a recipe where natural indigo can be used for printing, not just dyeing. He introduces me to his “indigo scientist”, textile designer Adeeph A.K.

If one isn’t an indigo junkie (there is a club across India: Jesus in Auroville, Sarvadaman Patel in Anand, Gujarat), one is sure to become one after this exhibit.

X@namratazakaria