The novel coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak and its recent predecessors—SARS, Ebola, Zika—should teach us that pandemics view the Westphalian state system with scant regard. When the face masks come on every few years across the globe, sovereignty and territorial integrity—the pillars of national pride and main triggers of aggression and war—sound hollow. It would be short-sighted to see such pandemics as someone else’s problem or seek safety behind national borders.

We are all in this together because disease outbreaks do not happen only in underdeveloped countries. The wealth, power or hubris of a nation provides little protection. Ancient Athens was humbled not just by Sparta but by typhoid during the Peloponnesian War. A smallpox outbreak did not spare the pharaoh Ramses V: his pockmarked mummy in the Cairo museum bears testimony. A few centuries later, the Antonine plague (smallpox or measles) hastened the demise of the mighty Roman empire, and claimed the wisest of Ceasers, Marcus Aurelius. In the sixth century, plague forced Emperor Justinian to drop his plans of bringing the Roman empire together and, in the 14th century, bubonic plague or the Black Death travelled in caravans from Asia to Europe and forced England and France to halt their war. European conquerors wiped out 90 per cent of the indigenous people of the Americas using smallpox, measles and bubonic plague. The first of several cholera epidemics killed a million in Russia in the early 19th century and travelled with British soldiers to corners of the empire, including to India where millions more lost their lives. The long list carries on down to our time. Just when China’s unstoppable political and economic rise had become a byword, it has been stung by the deadly Covid-19. It may well recover, but nobody is betting on how long that will take and to what extent.

This is not the time to gloat, or paint the outbreak country as a culprit, or mock its cuisine culture. But it is a moment to think of the politics of public health. Nations can be chary of admitting outbreaks in time or taking immediate steps, as has been the case in Wuhan. Other nations struggle to find a fine balance between the imperatives of self-preservation and maintaining good relations with the outbreak country, especially if it happens to be a powerful player. Responses can therefore be uneven, both in extent and alacrity. While India evacuated its citizens, suspended flights and cancelled visas, Pakistan fearing China’s ire has continued flights after a brief hiatus and refused to evacuate its people. Russia has clamped shut its 4,000km border with China despite the huge impact on trade and tourism while Hong Kong authorities, already facing anti-China protests for months, resist a full sealing off despite rising cases.

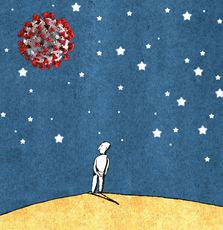

Politics should have no say in how the world deals with a deadly contagion. A WHO conference is required to define global principles for both outbreak countries and others: nations must be committed to full transparency; there should be no prevarication or delay, no matter what the cost; travel restrictions, quarantines and evacuations should be triggered by objective standards and not reflect bilateral power play. The WHO needs an objective standard itself: its repeated praise of China’s actions, refusal to label the outbreak a pandemic and discouragement of trade and travel restrictions have undermined its credibility. This WHO conference should ideally be held under a desert night sky full of stars. There is nothing better to remind us that we are but a speck in this universe and our national borders are just vainglorious lines in the sand.

The writer is a former high commissioner of India to the UK and ambassador to the US