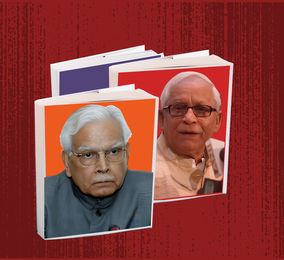

India lost two bibliophiles last week.

Inhabiting worlds that were poles apart, Natwar Singh and Buddhadeb Bhattacharya had little in common. One spent his adult days handling global power equations and trade deals, and his champagne-and-cognac evenings in the company of princes, presidents, prime ministers, and plenipotentiaries. A patrician to his pedicured toe nail.

The other, born a provincial patrician, sought to live a plebeian amidst "the workaday world of timecards”, waging wars over wages and working class rights, drinking cups of milky, sugary tea in cracked china or mud cups, and finally administering a state where he knew his ideology was getting rejected.

Natwar was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, one engraved with the coat of arms of Bharatpur’s Jat royals. And wasn’t he proud of his lineage? The best of his 13 books is on Suraj Mal, one of the several warrior-statesmen who galloped across the Indo-Gangetic plain in the 18th century and founded the Bharatpur state.

Buddhadeb was born with a silver stylus in his hand. He belonged to the Bengali gentry, learned, cultured, refined and known as the bhadralok, a stock which most early communists belonged to. His grandfather was a Sanskrit scholar, and his uncle a well-known poet.

Kunwar Natwar and Comrade Buddhadeb had one thing in common. Both had a passion for books, the arts and the sublime. They both read, read, read and read, discussed, lent, borrowed and gifted books. Who knows, they may even have stolen a few, and smuggled a few. And both loved the company of the cultured.

Indeed, it would have been easy for Natwar to make friends, having been born a royal, schooled in Mayo College, graduated from St Stephen’s, postgraduated from Cambridge, joined the diplomatic service and married the princess of Patiala. But friends are easily made, and tough to be maintained. Natwar knew it. So he maintained friendship by lending, borrowing, and gifting books to his friends and then corresponding with them about books.

Three of his books bear this out—Profiles and Letters, Yours Sincerely and Treasured Epistles. If the first is largely about people and a little about letters, the latter two are only about the letters that he wrote to and received from people who loved books—Indira Gandhi, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, P.N. Haksar, B.K. Nehru, R.K. Narayan, Michael Foot, E.M. Forster, Hiren Mukherjee, Santha Rama Rau and Raja Rao, to name a few. In the letters they discussed the books of J.K. Galbraith and Joyce Cary, Norman Cousins and Henry Kissinger, the athletic aesthetics of Russian ballet, the paintings of Rembrandt, and the music of Ravi Shankar and Vilayat Khan.

Buddhadeb’s network was less elitist but his biblio world was equally esoteric. He too loved to spend time with men of learning and refinement in Kolkata’s cultural hubs, rendered the works of Marquez and Mayakovsky into Bengali, wrote a play on the post-Babri communal tension, a 14-chapter book on the rise and fall of Nazi Germany, and a primer on the evolution of China from the age of the Great Wall to the globalised age of Alibaba.

Both ended their careers unhappily. Once he quit an illustrious diplomatic career, Natwar joined politics but couldn’t make much of a mark as a minister, and had to finally quit over the oil-for-food scam in which his son’s name figured.

And Buddhadeb? He sought to effect a rapid China-style transformation of post-feudal but pre-industrial Bengal into the industrial age, but fell against the great wall of popular resistance at Nandigram.

prasannan@theweek.in