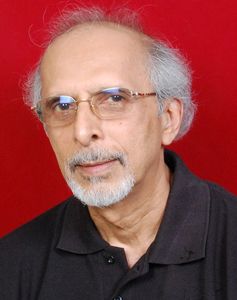

Interview/ Dr Chittaranjan S. Yajnik, director, diabetes unit, King Edward Memorial Hospital and Research Centre, Pune

Q/ The European study published in The Lancet identifies five subgroups of adult-onset diabetes.

A/ What we really need to study is how our types differ within our own population and from westerners. That is the purpose of our study. This research has been on for the last 30 years but this [latest] description from Sweden gives it a direction. As luck would have it, we have already got a grant for collaborating with the same group. It is an Indo-Swedish grant given by the department of science and technology and the Swedish medical council. The people who have written the paper in The Lancet about the five subtypes of diabetes are our collaborators, and even before the paper was published we were planning to do this. So we will now expand our ideas of the characteristics of Indian diabetic patients by comparing them with Europeans, especially Scandinavians.

Q/ Tell us about the concept of the 'thin-fat Indian' and how Indian diabetics are different.

A/ For 30 years, we have been doing research to find out why diabetes is so common in India. We have found that Indian diabetic patients have different characteristics from European patients. We have described this for many years in terms of Indian patients being shorter and thinner. But we showed in our research that when you measure the body fat with a special technique, Indian patients, though they look thin, are fat. And, they are fatter than Europeans. This is called the thin-fat concept and is named after me as I described the concept of a thin-fat Indian a few years ago.

Though not obese by international criteria, Indians are adipose—that is they have a high body fat percentage. Therefore, because diabetes is linked with excess fat in the body, we get it even though we look thin, and we get it at a younger age. In our research, we showed that Indians develop this thin-fat characteristic in the mother's womb. So we contributed to the idea called foetal programming of diabetes. We showed that the mother's nutrition is an important contributor to all this. India has had a history of undernourishment, famines and environmental stress, going back many hundreds of years. So Indians were used to living in difficult conditions with less food, less money and poor hygiene. All these things were part of our lives for years and our bodies are programmed to deal with these conditions. And suddenly, in the last 50 years, there was social and economic development, which brought about this epidemic of diabetes. We are now in a situation of relative plenty. Therefore our type of diabetes will be somewhat different from what has been described in Europe.

Q/ How will reclassifying diabetes help?

A/ Diabetes complications can cause economic and human loss, and must be treated effectively. Hence, if we are able to identify any sub types that are specifically predisposed to, say kidney damage, then it will be useful because we can treat them early. Those who already have diabetes need to be treated properly, and when we find different types and which treatment will be effective for them, it will help us improve treatment. The most common ones are type 1 and type 2, of which the latter is a very heterogeneous condition. Now, because of measurement of certain chemicals in the blood, we are going to be able to classify them.

Q/ Will individuals fall exactly into one of the categories?

A/ Never. Each person is an assembly of characteristics that are unique. This is a modern attempt at a systematic understanding of the disease. It will be put to test in clinical studies. Even in the WHO classification, there are probably 10 different types. But what we are saying is that the most common variety is the type-2 diabetes. We will try to reclassify it with more confidence into separate groups.

Q/ What do you think will be the conclusion of the study?

A/ There is a long way to go. Either we will conclude that our groups are similar to Europeans or they are not. And there is a hope that we will be able to personalise the treatment depending on the classification. But it will need to be clinically tested.

The Swedish classification is relevant to us, but if 10 per cent of Swedes have type A, 30 per cent of our people might have that. And something that is related to gross obesity in old age will be less common in Indians because our population is not that obese.

We will see a few thousand diabetic patients and will enrol them in the study. We will study what complications are common in groups 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, depending on whatever number of groups we find. Then, we start analysing it and decide whether we want to classify every patient the first time, put him into subgroups and treat him from the previous experience to prevent certain complications. Then, we will see after five or ten years if we have really achieved something. It is not just one cross-sectional report. We will also have to do a clinical study and trial to see whether such a classification is of any use to direct treatment, prevent complications and improve the quality of life.