I decided to slot only two days a week for anything junk, including wafers and cakes, but my mother-in-law just gives in to my daughter's demands every time she asks for a packet of chips.

My 10-year-old has been demanding to watch Netflix, and I have had to delete the app altogether. Now, nobody watches it.

We spent almost a fortnight looking for the right alternative and experimental school for our three-year-old.

My pre-teen just asked me if he could explore the dating site Tinder.

These are some of the voices that echo on the timeline of a parents' WhatsApp group that I am part of as a new, working mother. Posts keep streaming in through the day, and sometimes even late night when parents ask for tips on handling a colic baby, on the never-ending school project or simply for company as they stay awake with a sick child. To a large extent, this group, like several others across different social media, feed on the shared anxieties of young, new parents who come together to vent, advise, suggest, share and, at times, scare each other about everything related to parenting. It is rather parenting by millennials—the cohort born between 1980 and 2000—who are doing things differently from any other generation before them.

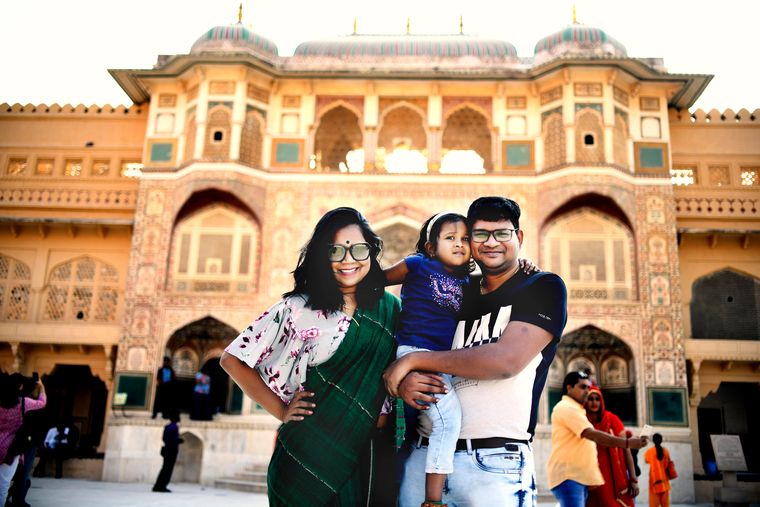

As per the US tech company Winnie, in 2017 millennials made up for 90 per cent of all new parents, thereby turning into a powerful force shaping the future of parenting. Experts attribute certain characteristics to the new-age parent: they are well-educated and constantly struggle to balance their own ambitions with parental duty, don't mind waiting until they are ready to have kids, enjoy documenting their kid's lives on social media to the extent of giving their kid her personal hashtag and YouTube channel, take to the internet for everything under the sun and beyond, unfalteringly check food labels with a micro lens, and are more involved in their children's lives than their parents were.

Dr Anupam Sibal, group medical director, Apollo Hospitals, says, “The problem with the present group of parents is that they cannot figure out how to say no to their children, how to have the children listen to them in the face of a technology clatter, and how to instil traditional values while at the same time opening them up for the ever-evolving modernism.” It is not just the millennials who have evolved to be smarter, informed and resourceful; their children have, too. And so, the conventional parenting rules do not apply anymore, says Sibal, a paediatrician and author of Is Your Child Ready To Face The World?. He explains with an anecdote: “My friend's seven-year-old son once told his grandfather who is 80-plus, 'Dadaji, you are wrong.' My friend was aghast because he never as much as raised his eyebrow in front of his father. When confronted, the son replied, 'Dad I am not like you who won't call out his father when he is wrong.'”

All experts concur that parenting has always been a challenge across generations and, in that respect, its nature has stayed the same. However, the milieu changes over the years bringing on a new set of challenges and conflicts for every new generation. Priya Krishnan, founder and CEO of KLAY Schools, says that parenting in an urban setup is a lonely journey. “The famous saying—it takes a village to raise a child—stands true no matter what time and age we are in. But this concept currently just doesn't exist, given the degree of urbanisation and the absence of a parental structure on which parents of today have been raised on,” she explains. She cites how parents turn to Google for something simple like how to treat colic instead of asking the elders in their own family. “In the absence of this framework, there is a lot of peer-based parenting, comparisons between parents and children and exchanging of notes happening,” says Krishnan. “Like, your toddler says good morning, while mine bangs her head against the wall. Now both these behavioural traits are perfectly normal for the age group, yet millennials will fluster over it.” This kind of behaviour, she says, has given rise to the notion of helicopter parenting, wherein a parent constantly hovers over every aspect of their child's life.

Manna Jaiswal, mother to a chirpy six-year-old in Gorakhpur, narrates how being too possessive and protective of her daughter affected her. “I would constantly monitor her and would tail her wherever she went,” she recounts. “Even in case of a common cold, I would call my mommy friends and take their advice instead of heeding to the advice of my own parents. Sometimes, it did work, but it put me in a situation where I found this control to be too suffocating.” She, however, agrees that there are parents who are at ease with the notion of 'letting go' and let the children thrive among a community of people than being under constant control.

New-age parents especially struggle to balance their need to be hands-on parents and their urge to carve their own identities outside home. This April, Maithilee Dange, mother of three-year-old Reva, decided to climb Mount Everest as a way of “coping with the stress of being a mother and rediscovering her lost self-esteem and self image”. Dange, a training and development consultant, had taken a sabbatical of three years to take care of her baby. By the end of it, she says she began to feel sorry for herself. “I was suffering from depression and would just cry at random, thinking how useless I appeared to others. Everest was a way to self-discovery,” she says.

Parenting can take a toll on marriage, too, like in the case of Disha Lal (name changed), 34, mother to a teenager. “Parenting in a way created rifts between me and my husband and that, in turn, has affected our son's psyche,” she confides. “We, as a generation, are not as tolerant as our parents were and are ready to be charged at the slightest provocation. So, between the two of us, there is no equal division of household duties, which has led to frustration. Soon, it will lead to our eventual separation.”

Most parents believe that a constructive role of the father has assumed significant importance in this day and age. Tarun Sakhrani, a banker who lives in London with wife Kathleen Gaile, a photographer, son Kian, 3, and two-month-old daughter Trisha, says the lack of time is eating into his relationship with his family. But it has taught him to manage time better and draw boundaries. “When I leave office and come home each evening, I make it a point to leave the office behind,” he says. “For those few hours in the evening, I will dedicate my time to just my kids, their meals, their bedtime and, most important, our nightly ritual of story time. Once they are down for the evening, I may then pick up work for a short period of time to catch up on any emergencies or key deadlines. And if, after that, there is some time, then I will dedicate it to myself—be it watching some telly, reading a book or simply meditating. Again, with only 24 hours in a day, many a time, I feel that I need to sacrifice on that me time to make sure I am being a good dad and a good husband.” Both Sakhrani and Gaile bring in different parenting styles, as he is from India and she from Manila. But both struggle to get their son away from Peppa Pig on his favourite device and on to the playground. Another difference in millennial parenting is the constant fear of everything, but he tends to be a bit flexible, says Sakhrani.

Communication and control on one's impulses are two sure-shot ways to good parenting, says Dr Avinash D'Souza, consultant psychiatrist based in Mumbai. And, it is here that the concept of rubber-band parenting comes into the picture. Parents are required to wear three simple rubber bands on the right wrist as a reminder to praise their children throughout the day, starting each morning. Every time you praise your child, you move a rubber band over to your left wrist, with the goal of ending the day with all three bands on the left wrist. The US version has five rubber bands moved to the other wrist whenever one loses patience. But to gain the bands back, one must do five positive things with the child, be it to dance, sing, read, or play chess. These concepts help in furthering the family bond while creating mindful parents.

According to D'Souza, changing family structures have a lot to do with changing patterns of parenting. We have moved from joint families to nuclear families and single parenthood, leaving young parents with more responsibilities, he says, and the anxiety of good parenting becomes all the more pronounced in the case of a family with an only child vis-a-vis one with siblings.

For Lakshmi and Milind Wankhede, both photographers, striking a balance between too much pampering and ensuring their five-year-old Myrah doesn't become selfish or lonely is a challenge. While both parents try to be hands-on parents, there are times when Milind has to stay away from Myrah for days on end. “There have been days when Myrah has cried for almost three hours at a stretch and developed a fever because her father was leaving her back home,” says Lakshmi. “She is quite attached to both of us, but we know where to draw a line when it comes to showering our love on her.”

In his book, Keys To Parenting The Only Child, author Carl Pickhardt talks about the many ways in which young parents can give their child the benefit of their mature understanding, as sharing of this kind allows the only child an opportunity for learning from the wisdom of parental experience. Reflecting on what he or she has been told, the child can learn to constructively manage his or her growth. The three thumb rules that parents of today must follow are: not to be judgmental, not to expect their children to live their dreams and not to compare their children with those of their peers. These three thumb rules hold true, irrespective of whether it is a parent from the millennial, Gen X or baby boomer generation.

Apart from dividing time and making room for a breather in the face of demanding duties, millennials, unlike previous generations, are doing a “great job by allowing their children to play a pivotal role in decision-making at home,” says Krishnan. They are also striving hard to equip their children with unique skills, be it music, dance or sports. In Sakhrani and Gaile's household, children are being raised to understand, accept and respect varied cultures, languages and religions. “In our household, Christmas is celebrated with as much joy and pomp as Diwali. When it comes to languages, Kathleen speaks to the kids in Tagalog; I use English and occasionally throw in Hindi and Sindhi words in our daily conversations.”

D'Souza, who specialises in the area of children and adolescence behaviour, says there are several parenting aspects where millennials are doing a better job than their predecessors. “Already, the kids of today are more well aware than their parents were at their age. So now parents have no choice but to mould themselves in ways that will suit the rapidly growing personality of their ward,” he says. “In the area of academics, these new moms and dads will encourage their child to learn from his mistakes than admonishing him over his marks or grades.” Also, new-age parents are more open to talk about sexuality and relationships. “These examples represent the entire psyche and thought process of the millennial parent, which is that he or she will not do what was done to them,” says D'Souza. “Rather, they would make the world a much better, safer, calmer and fun place to live for their children.”