During the years as a talk show host discussing medical research, I have had the opportunity to meet some awesome people and hear stories that inspire and motivate. Dr David Fajgenbaum’s is one of the most compelling ones that I have heard.

David has written a book—Chasing My Cure: A Doctor's Race to Turn Hope into Action—documenting his crazy decade-long battle with his disease and more recently developing a drug that he is using himself. With his book out in September, I cannot but reminisce about our chat.

“When I started medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, the first two and a half years of medical school were fine,” started off David. “I never had any medical issues and I was planning to become a clinical oncologist. I had lost my mom to cancer a few years before and I knew I wanted to be a doctor to treat cancer patients.”

However, things suddenly changed for David. He went from being this totally healthy third-year medical student to being sick in the intensive care unit with night sweats, weight loss and abdominal pain. His liver and kidneys began to shut down and bone marrow stopped functioning properly. And, he was hospitalised in the same intensive care unit at the University of Pennsylvania that he had previously worked in as a medical student.

He got sicker and sicker by the day with no diagnosis!

“It was absolutely terrifying to really lose grip on life, without knowing what it was that was making me so sick,” said David.

Fortunately, over the course of several weeks, David’s condition improved without any explanation. He regained consciousness and some of his organs began to work again, but still no diagnosis.

The relief was short-lived and David found himself back in the ICU with liver failure, kidney failure, bone marrow failure and in and out of consciousness. In fact, he was so sick the second time around that his physicians encouraged his family to say their goodbyes and a priest came in to administer the last rites.

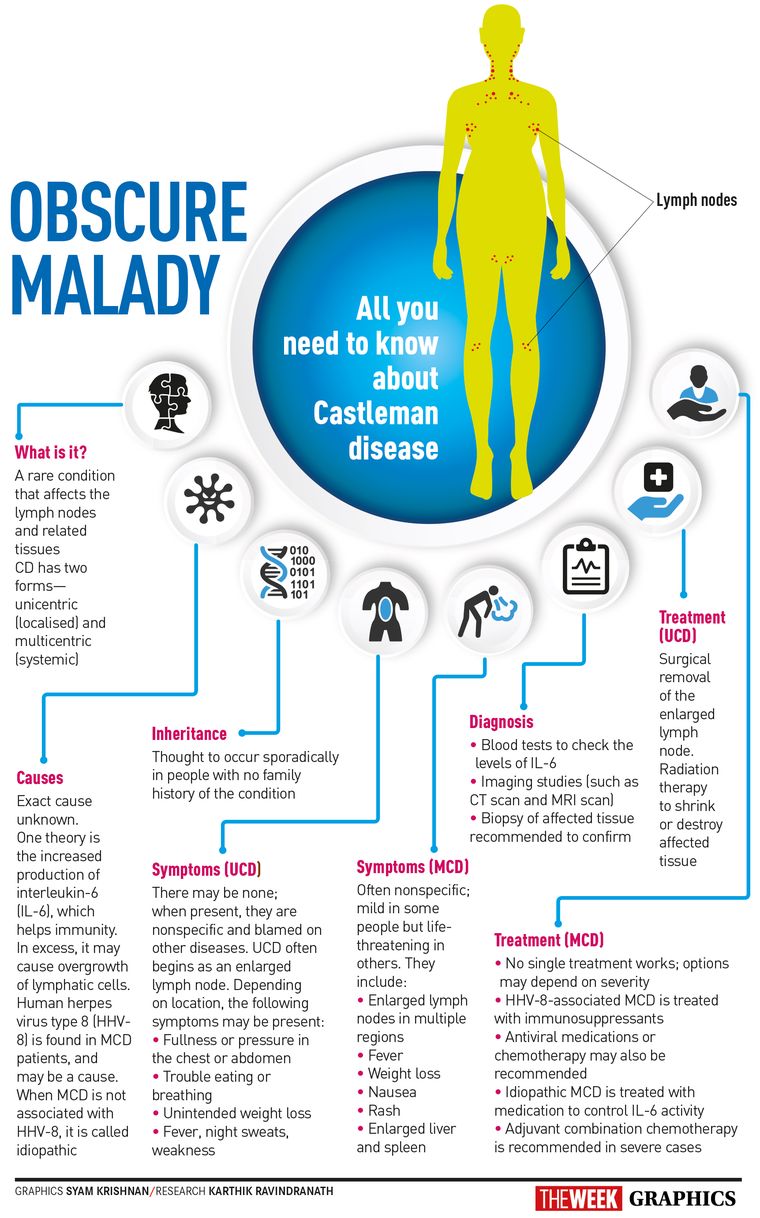

But right before that, an important diagnostic test was done—a lymph node biopsy. A review of his lymph nodes indicated that he had a disease called idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. This is a rare and deadly inflammatory immune system disorder, where your immune system gets out of control and begins to attack your healthy vital organs.

Castleman disease has been known since the 1950s but has remained largely a mystery. A hallmark of the condition is enlarged lymph nodes, and most people with the disease have a form that affects just one part of the body and can usually be cured through surgery.

The form ravaging David’s body—multicentric Castleman disease—is rarer and deadlier. Only about 1,200 to 1,500 people are discovered to have it every year in the United States. It defied classification, occupying a no man’s land between cancer and immune disease. Doctors weren’t sure of the cause in patients like him: some believed it was a type of cancer, while others thought it was an inherited genetic disorder, or was triggered by a virus.

One thing was clear: the disease was deadly.

Armed with this diagnosis, David’s doctors decided to start him on a form of chemotherapy to help turn around the disease. The first dose of chemotherapy kept him alive, but relapses began to happen needing more intensive regimens, including seven-agent combination chemotherapy. Finally, after six months in and out of hospital, David returned home and began to improve. He returned to medical school and back to his mission to treat cancer patients.

And then everything came to a halt again!

About one year later, David had another relapse of all of his previous symptoms, all of his previous organ failures and was back in the hospital. He was once again administered seven different chemotherapies. During this hospitalisation, he also learned that that there were no other drugs that were in development for Castleman.

This time when he returned to medical school, he wasn't back on the same track he was on before. This time he returned on a mission to take on Castleman disease.

He began conducting laboratory research in the lab at Penn, and decided to create a foundation called the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) to try to bring together researchers from around the world to push forward Castleman disease research.

“Research that really makes a difference needs to work across institutions. It needs to work across countries and needs to be highly strategic. We needed to all work together,” explained David on the need to set up CDCN. He then attended the Wharton Business School to pick up some skills. “You need to think really critically about what is the most important next step,” he said. “How do you utilise the resources available to you, whether they are financial or tissue samples or data? And a lot of those sort of decisions and ways to think about things are really not taught to you in either medical school or in PhD programmes. Those sort of operational decisions and strategic decisions are really kind of the bread and butter of the business world. And so, I felt that it would make sense to focus some time and do an MBA to try to pick up some of those skills.” And, it helped. “I really do think that that has had an important impact on the approach CDCN has taken to research,” said David. “We spend a lot of time thinking really critically about how to perform our research studies and how to make sure we are making the most of every dollar that we raise for research.”

Since he received the diagnosis, David had been collecting weekly blood samples and keeping track of his immune system, tabulating results. This time when the disease returned, he persuaded his doctors to remove a piece of a lymph node, test it and save it for future research.

After a round of chemotherapy, he improved enough to be discharged and started looking into what the tests might reveal. He observed that his immune system seemed to have started gearing up for a fight even though there was no apparent threat. His T cells, a key weapon in the body’s immune system, had started activating and he had started producing a protein call VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) in excess. This protein instructs the body to make more blood vessels.

He hypothesised that probably the problem was with one of the body’s communication lines, triggering overproduction of VEGF and T cell activation. If he could get his body to shut down that communication line—known as the mTOR pathway—he might be able to stop his immune system from overreacting and prevent a relapse.

He and his doctors explored existing drugs that were known to shut down the mTOR pathway. They discovered Sirolimus, also known as Rapamune, commonly given to kidney transplant patients to prevent their bodies from rejecting the organ. The drug had been on the market for years and was known to have a few serious side effects, but had never been used for Castleman disease.

David chose to become his own test subject.

“I had recently graduated from medical school and was certainly very early in my career,” he recalled. “But I made what was probably the most important decision of my young life to try this drug that had never been used before to treat Castleman disease.”

David, assistant professor at Penn Medicine's Translational Medicine and Human Genetics division, continues to lead research efforts of his own disease, and hopes to help raise awareness about Castleman disease through his work. He recently celebrated five years in remission. During this time, he got married. “And then my wife, Caitlin, and I had our first child, Amelia, who has brought us so much happiness in these first six months,” said David. “It was something that certainly when I was on my deathbed I never thought that I would see. It has been the most amazing experience of my life to be a father.”

Priya Menon is scientific media editor at TrialX/Applied Informatics Inc. She manages and hosts CureTalks, an international online radio talk show on cancer research and health care.