With her cherubic face and a smile that lights up her eyes, Kavya Solanki seems like any other toddler. Only, she is India’s first ‘saviour sibling’—born to save her thalassaemic brother. At two years, Kavya is obviously oblivious of what that means for her and her family and the community at large.

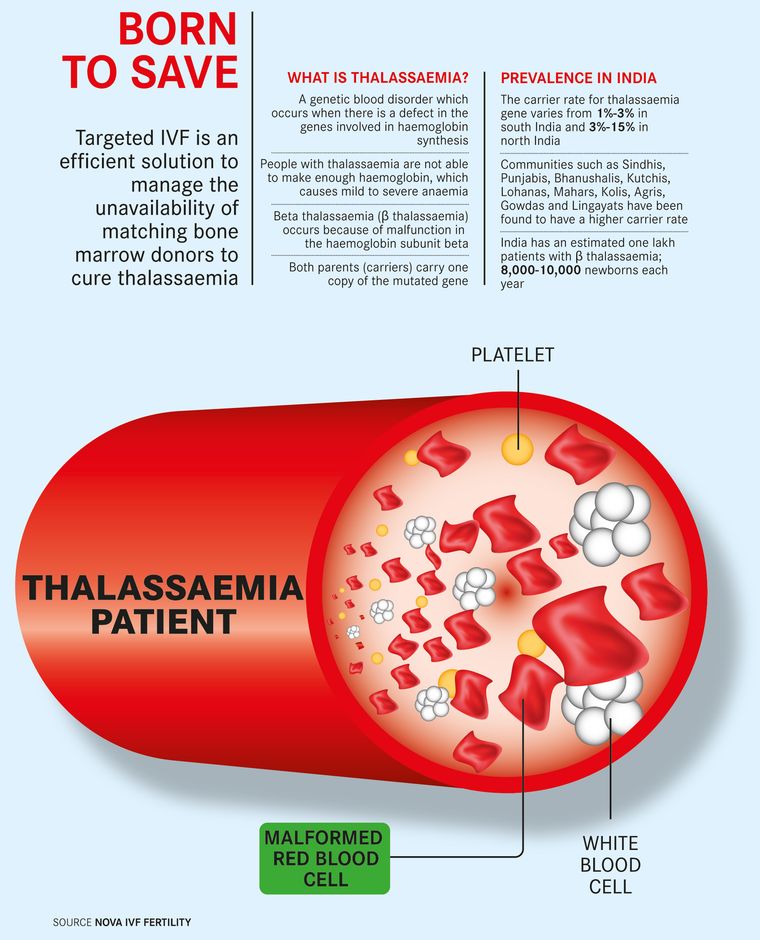

For her parents—Sahdevsinh and Alpa—Kavya has been a ray of hope and a source of joy after what had been a long, harrowing period in their lives. Their son Abhijit, 7, was diagnosed with thalassaemia major when he was eight months old. That meant his haemoglobin levels kept dropping, at times below five, which, in turn, affected the supply of oxygen in his body. Thalassaemia is a genetic blood disorder. Both Sahdevsinh, 37, and Alpa, 34, are thalassaemia minor, but they had no clue about it—they had no reported history of thalassaemia in the last five generations on both sides, they said. In case of thalassaemia minor parents, there is a 25 per cent chance of their child being either thalassaemia major or thalassaemia free; there is a 50 per cent chance of the child being thalassaemia minor. The Solankis’ eldest—nine-year-old Namrata—is thalassaemia free.

Post Abhijit’s diagnosis, blood transfusions became a part of his life, Sahdevsinh told THE WEEK. It began as a once-in-28-days cycle and eventually became once every 22 days. And, he had to be taken to Ahmedabad from Gandhinagar, where the Solankis are based, every single time as Sahdevsinh had registered Abhijit with Prathama Blood Center there that provided free services for thalassaemia patients. Abhijit would require one unit of blood (around 350ml) every cycle, and the transfusion would cost Rs250 per unit.

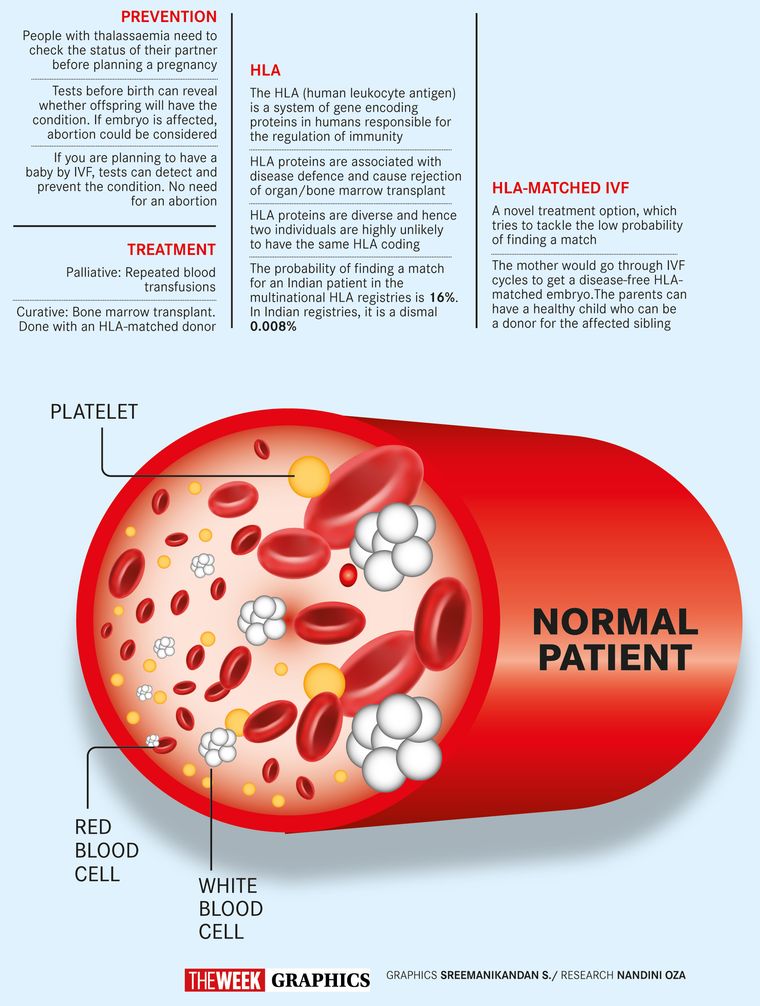

The only cure for thalassaemia, the Solankis were told, was a bone marrow transplant. For a successful transplant, Abhijit would need his human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matched with that of the donor. HLAs are a set of proteins responsible for the regulation of the body’s immune response. If the HLA doesn’t match, the body will reject the transplant. Sadly, neither Abhijit’s parents nor Namrata were a match.

So, Sahdevsinh, a gazetted class I officer in the Gujarat government’s Narmada and water resources department, started looking for an unrelated donor. There is a 16 per cent chance for an Indian patient to find an unrelated marrow donor in multinational HLA registries, but just 0.008 per cent chance in Indian registries owing to the lack of donors. Despite the dismal statistics, Sahdevsinh did not give up. He trawled through the internet and spoke to parents of other thalassaemia patients. His research led him to the Christian Medical College, Vellore. “CMC put us through to a registry from where we got an unrelated HLA matching donor from the US,” said Sahdevsinh.

Sourcing the marrow and transporting it to India and finally getting the transplant done would have cost the Solankis Rs50 lakh. It was way beyond his means, and Sahdevsinh started saving up for it. “Believe me, even though I am a gazetted officer, I do not have a car,” he said. For Abhijit’s blood transfusions and check-ups, he said he would exchange his two-wheeler with his father’s 12-year-old car for the trip to Ahmedabad. Sahdevsinh decided to pay for the transplant by using the gratuity and provident fund of his father Sardarsinh and by selling a part of the land owned by his family.

In April 2017, when Sahdevsinh and two of his relatives were in Vellore to finalise the date for Abhijit’s admission, he came across an article on saviour siblings. The article spoke about how the probability of a matched donor increases through in-vitro fertilisation. And, that changed Sahdevsinh’s approach. He had already paid more than Rs2 lakh to get the bone marrow from the US. But he told the doctor to put the procedure on hold for two months. “I was told that the procedure would have to be done all over again and I will also have to shell out money again,” he said. “I was fine with it as the success of matching HLA is much higher in related donor than in unrelated donor.”

Sahdevsinh then did what he has been doing ever since Abhijit was diagnosed with thalassaemia—research. He read up extensively on IVF and bone marrow transplant. And, that is how he landed at Nova IVF Fertility in Ahmedabad. Said its medical director Dr Manish Banker: “I did not have to convince them as the father was well-informed. He had studied well before coming here. I only had to explain the procedure.”

In case of the Solankis, it was not only necessary to have a disease-free embryo, but one with a matching HLA, too, so that Abhijit could be cured. Over six months, Alpa underwent three IVF cycles, which resulted in 18 embryos. These were screened for disease-causing genes using pre-implantation genetic testing. Of the 18 embryos, only 10 were found fit. However, the HLAs in only two embryos matched with Abhijit’s, and one of these had chromosomal abnormalities. “So only one satisfied all criteria,” recalled Banker.

The healthy embryo was then transferred into the uterus. Banker and his team kept their fingers crossed, as they waited for Alpa to get pregnant. “Had she not then the entire effort would have gone waste,” he said.

A fortnight later, reports indicated that Alpa was pregnant. But there were a few bumps ahead. “During her pregnancy, Alpa bled twice,” said Sahdevsinh. “Once in the third month and once in the eighth month. Luckily though, it did not result in a miscarriage.”

On October 30, 2018, Kavya was born. The next task was to match Kavya’s HLA with Abhijit’s. Earlier, it was the HLA of an embryo that was matched. “The match was 10/10,” said Banker. The success of an IVF programme depends on how well an embryo is created, how good the IVF laboratory is, what time the medicines are given and when the eggs are extracted, he added.

Even while going through the IVF cycles, Alpa managed to take Abhijit for blood transfusions. “Had it not been for the joint family, IVF cycles would not have been possible,” said Sahdevsinh. He and his family stay with his parents. Also, he said he and his family drew strength from his spirituality. Right from the beginning, there was something that continued to help them and things kept going in the right direction, he said. He cited the time they were about to finalise the unrelated marrow donor and how he came across the article on saviour siblings. He added that he had insisted on the third IVF cycle, should there be no problem for Alpa. “Kavya is the result of the sixth embryo of the third cycle,” he said.

The Solankis waited for a year and a half after Kavya’s birth for the bone marrow transplant. The doctors wanted her to gain 10kg before the procedure. In March 2020, Abhijit was admitted to Sankalp-CIMS Centre for Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplantation. Before the doctors could start the procedure, the parents’ assent was taken on camera; children above seven years, too, have to give the go-ahead on camera. Next, the HLAs of Abhijit and Kavya were matched again. His head shaved, Abhijit was given chemotherapy to dry up the existing bone marrow that had thalassaemia-producing cells. Once the bone marrow had dried up, Kavya was admitted to the centre on March 17. Extra precautions were taken as Covid-19 cases had started spreading across the country. Kavya was administered anaesthesia and was made to lie down in a prone position. Thereafter, the marrow was extracted from both her pelvic bones. “About 200ml to 400ml is extracted depending on the weight of the donor and the patient,” said haemato-oncologist Dr Deepa Trivedi, who performed the procedure. The marrow was taken in a plastic bag, just like blood, and administered intravenously to Abhijit.

Kavya was discharged the next day after her haemoglobin levels were checked. She was put on multivitamins and iron supplements. Abhijit was discharged on the 16th day after the transplant. The procedure does not take long but the patient is kept under observation for a fortnight or so. That is a critical period, as after transplant there can be internal bleeding and the patient can die, too, said Trivedi. It takes about 10 days for the white blood cells to grow, and during this time the patient is at a greater risk of developing infections.

Abhijit, fortunately, only developed some mouth sores. He watched television and moved around in his room. While at the hospital, only Alpa was allowed to stay with him; the nurses went in only when called. “Vital parameters of the patients are monitored through a glass window,” said Trivedi, who trained at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in the US.

Like all other bone marrow transplant patients, Abhijit, too, was put on immunosuppressant drugs. He will be on these drugs for a year, during which they will be gradually reduced, said Trivedi. The drugs are given to ensure that the body does not reject the bone marrow. The total cost, including the IVF, came to around 019 lakh, thanks to the subsidised rates provided by CIMS through Sankalp India Foundation. The foundation also pays for the one-year followup and medicines of thalassaemia patients. Sahdevsinh paid for the treatment from his father’s gratuity and provident fund.

Abhijit is now cured and no longer needs blood transfusions. Owing to Covid-19, both he and Kavya mostly stay indoors. While the possibility of a ‘saviour sibling’ has given hope to parents and patients, doctors harp on the importance of testing, irrespective of whether the parents are thalassaemic or not. In worst-case scenario, the foetus can be aborted.

“Why can a simple test not be made mandatory to detect thalassaemia?” asked Sahdevsinh. “I told the gynaecologist where Abhijit was born that it was due to her carelessness that we were in such a position. The doctor, he said, had no answer.

Trivedi said that thalassaemia patients could develop heart ailments, liver problems and issues with sexual organs. Also, one cannot keep getting blood transfusions as that can lead to other health problems. “It also creates much pressure on the blood banks,” said Trivedi. Abhijit, she said, was lucky as the chances of finding an HLA match in your sibling is about 25 per cent and rejection 5 to 10 per cent.

But what about Kavya? Is she just a means to an end? A mere commodity? These questions were raised by those who viewed the saviour sibling concept as unethical. Similar questions were raised when Adam Nash, reportedly the world’s first saviour sibling, was born in the US in 2000. His sister, Molly, was born with Fanconi-anaemia, a rare disorder that affects the bone marrow.

“This ethical and unethical debate will remain,” said Trivedi. “However, parents have medico-legal rights to grant permission for such a procedure if the child is a minor. The permission of the child has to be taken if he or she is an adult.”

The fear that using pre-implantation genetic testing could encourage the making of ‘designer babies’, said Banker, was misplaced. At this juncture, we cannot create designer babies, he said, pointing out that even if that is to become a reality in future, we should not stop its use for something good just because there is a potential for misuse. “We should stop the misuse, and not the good use. It should be regulated,” he said.

Sahdevsinh said that only people in his family’s position would understand their plight. “In our case, the intention has to be seen,” he said. “Did we want the baby for particular qualities? Or, to give a healthy life to our son? Consider the fact that such a treatment is available but I do not go for it, isn’t that unethical?” For parents, he said, a child can be unplanned but never unwanted.