Two weeks ago, Prerna Dhawan lost her life to stage IV lung cancer. Her husband and daughter Aarti, 20, are still in a daze as it all happened so fast. Dhawan, in her sixties, showed no symptoms. She went about her daily chores which included a walk in the park, reading books, doing the laundry and cooking elaborate meals. A month ago, she vomited blood. That is when the diagnosis surfaced—a tumour had been growing inside her body for years. It had already spread to both her lungs and nearby areas and even distant organs. The family was shocked and shaken. The doctor told them that it was “already too late for treatment”, and advised palliative care to ensure that her remaining days were pain-free. She was gone within a month of the diagnosis. Even today, as the family struggles to come to terms with her death, one question haunts them: would things have been different had she been diagnosed in time?

As cancer continues to emerge as the number one killer worldwide, that question becomes increasingly significant as in most cases the tumours are detected only after they have taken a form or shape. And by the time the symptoms show up, the cancer may have advanced and spread, making it too lethal to be cured. This is true for almost all types of cancers. Take, for instance, ovarian cancer in which the symptoms can often be confused with those of other ailments or dismissed as menstrual cramps. Only regular screening helps in early diagnosis. Even then, the screening helps only after the cells have mutated to form a lump. The treatment begins after a PET scan or a CT scan shows imagery that confirms the tumour. Often scans do not spot tumours if they are very small, weigh less than a gram and are spread in micro particles in the blood.

Experts concur that if we are to rein in this silent killer, it is pertinent to identify it in the blood right at 'stage zero' when it first becomes apparent, much before it begins to start forming or multiplying. And this is precisely what the latest research published in the April issue of SCRR (Stem Cell Reviews and Reports) talks about: a blood test to diagnose 25 types of cancer.

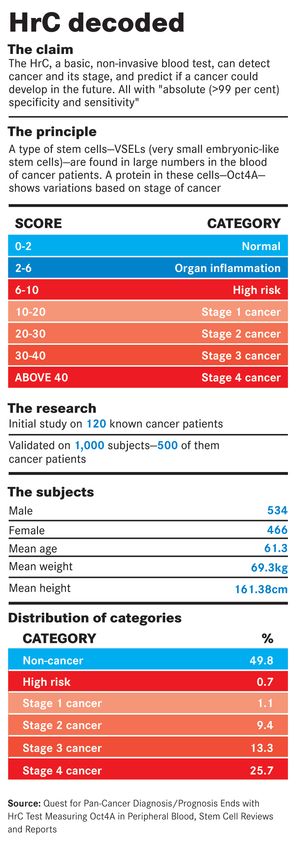

Helmed by molecular medicine expert and scientist Dr Vinay Kumar Tripathi and his investment banker son, Ashish, the paper claims to have made the discovery of a unique gene marker that allows for early detection of all types of cancer when the disease is still in-situ, meaning it is still limited to the place it started without spreading to nearby tissues. If validated by additional trials, this discovery could mean that a basic blood test—named HrC—can not only detect cancer and its stage but also predict if one can get it in future. And all of this, the paper claims, is with almost 100 per cent accuracy.

This discovery, says Ashish, CEO of Tzar Labs, is based on the principle of stem cells, which have the ability to regenerate and develop into other kinds of cells. But the type of stem cells that led the Tripathis and their team to come out with a diagnostic tool for cancer, are the VSELs (Very Small Embryonic-Like stem cells) that are ubiquitously circulating in the body. “We found a large number of VSELs in the circulating blood of patients with cancer as against those without cancer, and the expression of protein Oct4A within the cell showed variations according to the stages of cancer,” Ashish tells THE WEEK.

The team developed a HrC test scale, based on observations in a group of 120 cancer patients and then re-tested it in a clinical trial with 1,000 people, half of whom were cancer patients. “Cancer patients and the stages they were at were identified with 99 per cent accuracy and we were also able to tell whether or not non-cancerous patients have the risk of developing cancer,” says Ashish.

As per the paper, the HrC scale can detect cancer, predict and monitor treatment outcome, is superior to evaluating circulating tumour cells and can also serve as an early biomarker. An HrC score in the 6-10 range is categorised 'high risk', as it means that the number of VSELs in the bloodstream is significantly elevated as compared to the 'normal' range (0-2). This range precludes ordinary infection, organ inflammation or other disease states, as only cancer-causing gene mutations reflect in this range. The team postulates that a high-risk score might indicate the emergence of cancer stem cells and thereby the underlying proclivity of a person towards developing cancer. When the HrC score is in the 8-10 range, the team categorises it as “cancer imminent”. It signals that cancer-causing gene mutations have already occurred, hence the observed increase in levels of VSELs and the Oct4A biomarker. It also indicates that cancer cells have formed in the primary location. A score of 10-20 is indicative of stage I cancer, 20-30 of stage II, 30-40 of stage III and above 40 of stage IV. For instance, in a 49-year-old non-cancerous male patient, the HrC score was 7.20, indicating high risk. “The patient was an active user of pan masala and gutkha and a regular smoker. In-depth analysis revealed that the subject was at risk of developing oral cancer,” reads the paper. As against this, in a 68-year-old male patient with liver cancer, the HrC value was 40.15, indicative of fourth stage liver cancer. “HrC test was able to accurately detect the stage of cancer,” reads the paper. “A detailed mutational analysis revealed lymph node metastasis, primary and secondary organs like the liver and lung metastasis.”

The HrC test, according to the Tripathis, is a non-invasive test that can predict, screen and diagnose cancer with absolute (>99 per cent) specificity and sensitivity. Put simply, from a blood test, they try to extract a patient's DNA or genes and calibrate the mutations in the DNA to see if they point towards cancer. “The difference between the HrC test and the liquid biopsy techniques used by companies globally is that while the former tries to read a genetic signature it has found to correlate with cancer, the others depend on examining tiny particles of broken tumour, circulating in the blood, to make a diagnosis,” explains Ashish. “We are superior in that sense because we took a completely different approach.”

The family has now filed for patents in the US, Japan, Europe, Singapore, South Korea, China and India. The HrC test has been co-developed by Epigeneres, a Mumbai-based firm that holds the exclusive licence for the test in India, and Singapore-based Tzar Labs that holds the intellectual property rights for the invention; the family is a majority stakeholder in both firms.

But this is not what Epigeneres had initially set out to do. The finding of the biomarker “just happened” while the team was working on finding a cure for cancer. And, while they were debating on whether to delve deeper into this discovery or to continue on the path towards curative cancer medicine, the Tripathi family was going through a period of deep turmoil. Having lost four grandparents to cancer already, the three Tripathi brothers—Anish and twins Amish and Ashish—lost their only brother-in-law Himanshu Roy, who was former additional director general of police, Maharashtra, in 2018 after suffering from fourth stage renal cancer. At the time, Roy's death, widely reported in the media, steeled the family to aggressively pursue cancer research, especially diagnostics. With Roy, cancer had come knocking again 16 years after he first fell prey to it. Except a nagging pain in the calves, there were no symptoms. Roy and wife Bhavna, both gym regulars, initially thought it was a gym injury as Roy first experienced the pain after a workout session. “There was just no other symptom except for that pain,” says Bhavna, who reportedly quit the IAS to be with her boyfriend-turned-husband. “But at the time we thought it was just any other injury and did not take it seriously. He even showed it to a sports medicine expert who then suggested that he do an MRI because the pain just wouldn't subside. The MRI pointed towards a fully formed tumour in his fibula, which required an emergency surgery.”

Bhavna says the family embraced his death. “He said that he did not want the disease to take away his dignity,” says Ashish. “Even in his death, he conquered cancer.” Amish, a renowned author who dedicated his recent books Suheldev & The Battle of Bahraich and Dharma: Decoding the Epics for a Meaningful Life to Roy, talks fondly of him. “He had this strict, tough cop image for the outside world. Within the family, he was warm, kind, protective and loads of fun,” he recalls. “He had a wicked sense of humour, and would have us in splits in family get-togethers. Our social life was largely restricted to our immediate family; primarily eight of us—the four siblings and our spouses—with Himanshu da as our patriarch, our collective elder brother!” It was around 2018, sometime before Himanshu's death, that the Tripathis discovered the biomarker. “Dada knew we were working on this and he was very proud,” says Anish, COO of Epigeneres. “We only wish it could be of help to him. The tragedy became a collective trigger for us to bring out a diagnostic tool that could place the most stubborn, hidden tumours by way of a blood test.” And that is how the test got its name: HrC for Himanshu Roy Cancer.

At present, with the exception of blood cancers, blood tests cannot absolutely tell whether you have cancer or some other noncancerous condition. But they can give the doctor clues about what is going on inside the body. In addition, noncancerous conditions can sometimes cause abnormal test results. But in other cases, cancer may be present even though the blood test results are normal. And it is in this context that the discovery of the HrC biomarker becomes even more significant.

“There is no doubt that scientists are looking for the exact marker for cancer cells which can help us in detecting it at very early stages and can tell a person if he or she has cancer much before the disease can cause an impact,” says Dr Rama S. Verma, professor, Stem Cell and Molecular Biology Laboratory, IIT Madras. “But then, these VSELs are very difficult to catch hold of as they are extremely small, largely indistinguishable and widely spread in the body. If successful, this blood test will be a major breakthrough, but it needs thorough validation through additional research.” Agrees Professor Ajaikumar Kunnumakkara from the department of biosciences and bioengineering, IIT Guwahati. “This is a very important discovery, because till date we have not been able to find a specific marker for cancer and most of the cancers are asymptomatic, which makes it even more challenging. This discovery would lead to the diagnosis of cancer, to identify the susceptible population and importantly in the pre-cancer stage.”

The discovery of Oct4A in itself is not novel, say experts. But it is the way in which it is interpreted by the Tripathis and their team that makes it unprecedented. “Oct4A is found in different stages of cancer, therefore this would help in treatment of different types of cancers. Also, it will keep away arbitrary diagnosis which is rampant now, by helping clinicians decide what treatment should be given to the patient,” says Kunnumakkara. “The expression of this protein in non-cancerous patients is very less, but in cancerous patients it is 40 to 50 times [more], which is huge. This is more accurate than others. However, what remains to be seen is if they can place it successfully across populations and places.”

Agrees Dr Dilip Nikam, professor and head, radiation oncology department, Bombay Hospital, adding that a number of important issues regarding Oct4A remain to be addressed. “Vinay Kumar Tripathi et al showed us that Oct4A is a good marker and can be studied further,” he says. “Curiously, very little is known about it beyond its ability to regulate gene expression. The mechanism by which it specifies totipotency [ability of a single cell to divide and produce all of the differentiated cells in an organism] remains entirely unresolved. And an increased understanding of Oct4A function in stem cell biology could also lead to novel ways of detection and treatment of multiple malignancies.”

Yet, the Tripathis are quick to point out that this does not mean the blood test alone will suffice in making a diagnosis; it has to be accompanied by a PET scan and a biopsy as well, they say. The family hopes to get approvals for further trials so as to speed up the process of making the test available as soon as possible. “We are not entirely ruling out a company buy-out,” says Ashish, “but as of now we can't wait for our first laboratory to come up in Mumbai.”