Delhi-based writer and filmmaker Vandana Kohli's tryst with Covid-19 began last November when her husband Rajat Sethi, a corporate lawyer, tested positive. Four days later, she tested positive, too. Rajat, thinks Vandana, picked up the virus from his office conference room that was earlier used by a colleague who had conjunctivitis. The couple later learnt that conjunctivitis, too, could be a symptom of Covid-19.

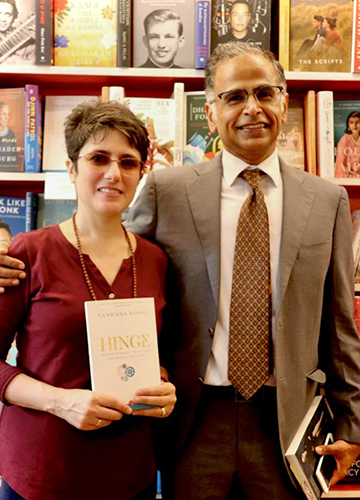

Vandana knew that time had come to manage everything on her own for at least a few months. She asked her domestic helps to stay home, while continuing to pay their salary. It was challenging to pull off daily household chores, coupled with their own work responsibilities, but the strategy was to immerse themselves in work to an extent that the emotional upheaval of living with Covid-19 day after day was kept at a minimum. Rajat had fever for five days, but he chose to continue working and also took up online classes for students from the National Law School in Bengaluru. Vandana, too, kept herself busy with the release of her book on emotional wellness, Hinge.

While Rajat was battling fever that would keep fluctuating every evening, Vandana was struggling with brain fog. “I couldn't think clearly,” she says. She also went through bouts of terrible breathlessness. Delhi’s winter added to her misery. “I kept coughing like a maniac,” she recalls. A high resolution CT scan found a patch of mild pneumonia and she was prescribed Fabiflu and steroids for 25-30 days. What made it worse was the persisting weakness that lasted for months, making it “impossible to lift the body to do even the basic chores,” says Vandana. “But once you are in that situation, nobody thinks of cleaning. So even if no help is coming over for a week or more, it is fine. Every three to four days, I would do the basic [cleaning].”

A couple of months later, as life was gradually crawling back to normalcy, Vandana's brother, Nalin, and her septuagenarian parents, Anupama and Amolak Rattan Kohli, tested positive. At the time, her brother and her parents were near Chandigarh. The family’s ordeal began when Nalin, who had first tested positive, had to isolate himself inside a room, leaving his aged parents to themselves. A recovering Vandana, who still hadn't gotten back her full sense of smell and taste and would be fatigued at the slightest exertion, now had the responsibility of catering to another house infected with Covid-19. A few days later, both parents, too, tested positive and the entire responsibility of managing the show fell on Vandana, who kept flitting between the two homes. “Whatever they would need, I would leave out at the doorstep, stand near the window and communicate three to four times a day,” says Vandana. “The neighbour, too, was extremely empathetic and sent lots of food home.” The family panicked when Anupama, a borderline diabetic, developed high fever and her oxygen levels dropped to 80 and pulse to 75. She couldn't stand and had to be rushed to the hospital. This happened twice. “It was crazy. It's not like once you catch the infection, you can simply go back to your couch and watch TV at home,” says Vandana. “The sheer anxiety of having Covid-19 and the fatigue it causes keeps you on tenterhooks at all times. As a family, our perspective on life changed.”

In Mumbai, Charu Mehra, 39, “struggled to make sense of the world,” when she, along with her teenaged niece and sister-in-law tested positive four months ago. “It was as if the entire house had come to a standstill because it is essentially my sister-in-law and I who manage the show on a day-to-day basis. And with us stuck inside our bedroom, there was panic in the house,” says the homemaker. Though she has tested negative, she still feels fatigued.

The seven-member Mehra family lives in a two-bedroom flat in Mumbai. Apart from the virus, Charu says she was also battling a sense of guilt on two counts. “That one of us would be blamed for getting it into the family or for passing it on to others,” says Charu. “And then that as daughters-in-law we were being served food in bed. What would the mother-in-law think? All of it was emotionally draining for me.”

Also, Covid-19 brought the underlying fissures to the fore. “The interpersonal chemistry between all of us was rapidly undergoing a remarkable shift,” says Charu. “We had never spent so much time together and it was a testing time for us as a unit. There was bitterness, annoyance and frustration, mostly over the additional domestic workload that everyone had to bear. At one point we did shout at and blame each other, but then we have tided over it as one unit and that makes it memorable.”

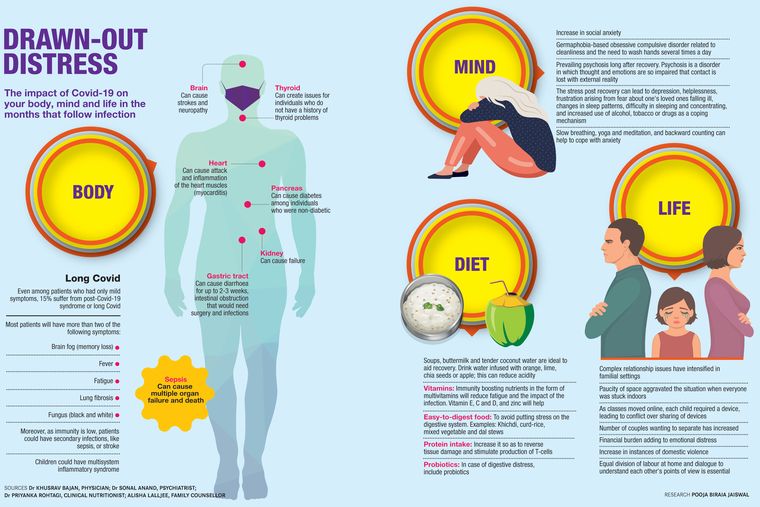

The pandemic has been an intensely challenging period for family life, uniquely affecting families by disrupting routines, changing relationships and roles. Additionally, with child care, school and recreational activities being closed and family gatherings limited, families are going through periods of emotional turmoil and fractured relationships. Stress from Covid-19 has been compounded by additional responsibilities for parents and grandparents, too, as they adapt to their new roles as educators and playmates for children, even as they cope with work-related stressors. At the same time, experts concur that family members are spending more time with one another, thereby knowing each other better and more importantly feeling empathetic towards one’s own.

“Only after Covid struck did we all realise the significance of my mother's role in the house and the seamless manner in which she pulled off all familial duties, which we now found to be an enormous challenge,” says Surabhi Kumar, 26, a public relations consultant in Kolkata. The family of four, including her 19-year-old sister Subhangi, a law student, got infected with Covid-19 this March. “On knowing that we were all positive, the first few hours were spent panicking—how would we manage everything, get the essentials, do the household chores day after day—because until now nobody had ever given much thought to these things except for our mother,” says Surabhi. Surabhi and her father, a government employee in the excise department, had mild symptoms like fever and body ache. All four of them experienced “extreme fatigue”. “For a week post diagnosis, we could divide and distribute the chores between us. But post that, as fatigue took over, it became increasingly difficult to even get out of the bed,” says Surabhi. “None of us really wanted to do anything; not cook, wash or clean. We had so much weakness that getting up to get a glass of water was difficult. It was nothing less than a Big Boss challenge. The chemistry between us had become a bit stressed, too.”

Says consultant pulmonologist Dr Lancelot Pinto of P.D. Hinduja hospital, Mumbai, “There is no doubt that it pushes one to the limits to have everybody in the house unwell, especially down with Covid-19.” He talks about heart-breaking situations where both the husband and wife are admitted in the hospital at the same time, and one passes away and the other remains oblivious to it. Or, families with just a single, healthy young member caring for three elderly people, especially when he himself is stressed and fatigued with excess work. He talks about the peculiar challenges faced by new mothers, with no outside help and having to juggle homely chores with the continuous attention demanded by a newborn. “Add to that, the stress of infection from Covid-19 and the challenges compound instantly,” says Pinto. He narrates an incident where a two-year-old child had nowhere to go as both his parents were Covid-positive, and his grandparents weren't sure of taking care of him as they, too, were vulnerable in terms of age and immunity.

For Chaitali Pathare, 30, the challenge was to look after her 61-year-old father and 53-year-old mother, both of whom tested positive. Chaitali lives in a joint family of six with her parents, younger brother, an aunt and her daughter. They live in two 2BHK flats facing each other on the same floor of a society in Thane. Early morning on April 21, Chaitali’s mother informed her that her father was feeling uneasy and feverish. Chaitali assumed the worst and asked her mother to let him isolate. Given that her father was used to travelling around in Mumbai for work, she suspected it to be Covid-19, because otherwise, she says, he is “fit as a fiddle”. “At the time it was the peak of the second wave and so we immediately got in touch with those who had recovered from the first wave and they suggested a battery of tests and a list of medicines,” says Chaitali, who works in a private firm. “The very same day, we got him tested and the reports came the next morning. He had tested positive. We all isolated ourselves and my mother moved from the bedroom to the living room from day one. Three days later, she had fever. Next morning, she, too, tested positive.”

Even as she was taking care of her parents, Chaitali worried that she, too, might contract the disease. But she tested negative thrice. Her father took medicines only for fever and from the seventh day of testing positive, he began feeling better. Her mother, however, had persistent fever, and on the eighth day, her oxygen levels dropped. She was hospitalised for five days.

“What worked for us was that we assumed the worst from the very first symptom and started taking precautions,” says Chaitali. “We isolated ourselves, wore a mask at all times, even indoors, consulted a specialist who could guide us properly and had a backup plan ready—list of nearby diagnostic centres, hospitals and ambulances with their contact details.”

Experts suggest having a network of trusted people one can talk to regularly and who can help during the situation. “It is really important to have the right doctor to guide you,” says Chaitali. “Many people from their personal experiences advised us to get CT scans done, which was discouraged by our doctor. We did a simple X-ray and that too only for my mother. Other than that, it was just the standard three blood tests—CBC, CRP and D-dimer—for monitoring the level of infection, and taking proper medication, if necessary.”

What got to them though was the overload of information, be it from the media or well-wishers, says Chaitali. “It became tiring after a point because there was nothing else they were talking about,” she says. Her parents, too, kept talking about Covid-19, even on phone with relatives and friends.

The extent of the impact of Covid-19 also depends on the resilience displayed by the family, says psychiatrist Dr Avinash De Sousa. “That has a lot to do with which family member is affected,” he says. “With the breadwinner, children and the elderly contracting Covid-19, the resilience of the family breaks down.”

Severity of the disease also plays a role. “While mild symptoms won't matter, serious complications including hospitalisation and death can totally shake up the familial constellation,” says De Sousa. He lists coping mechanisms in such situations. First, one who is least affected takes charge and starts managing. Second, have a counsellor speak to them online. Third, a psychiatrist or mental health professional should be made part of the treating team, especially when entire families are affected. Fourth, speaking to survivors of Covid-19, especially other families that have been down that path and have emerged stronger together, will help. Fifth, neighbours also play a very important role here and it is important that they are sensitive towards the situation.

De Sousa also cautions families who have members with a history of mental health issues. “If there is any family member who has had a previous history of a psychiatric problem, then they need to be extra cautious,” he says, “because the risk of them relapsing is high as they get surrounded by negative information on the disease.”