She grew in a glass jar as an embryo and was later placed in her mother’s womb.

Louise Brown, the world’s first baby conceived outside of the human body, celebrated her 43rd birthday this July 25. “I was subjected to more than 100 tests after my birth to ensure I was a ‘normal child’,” she told THE WEEK.

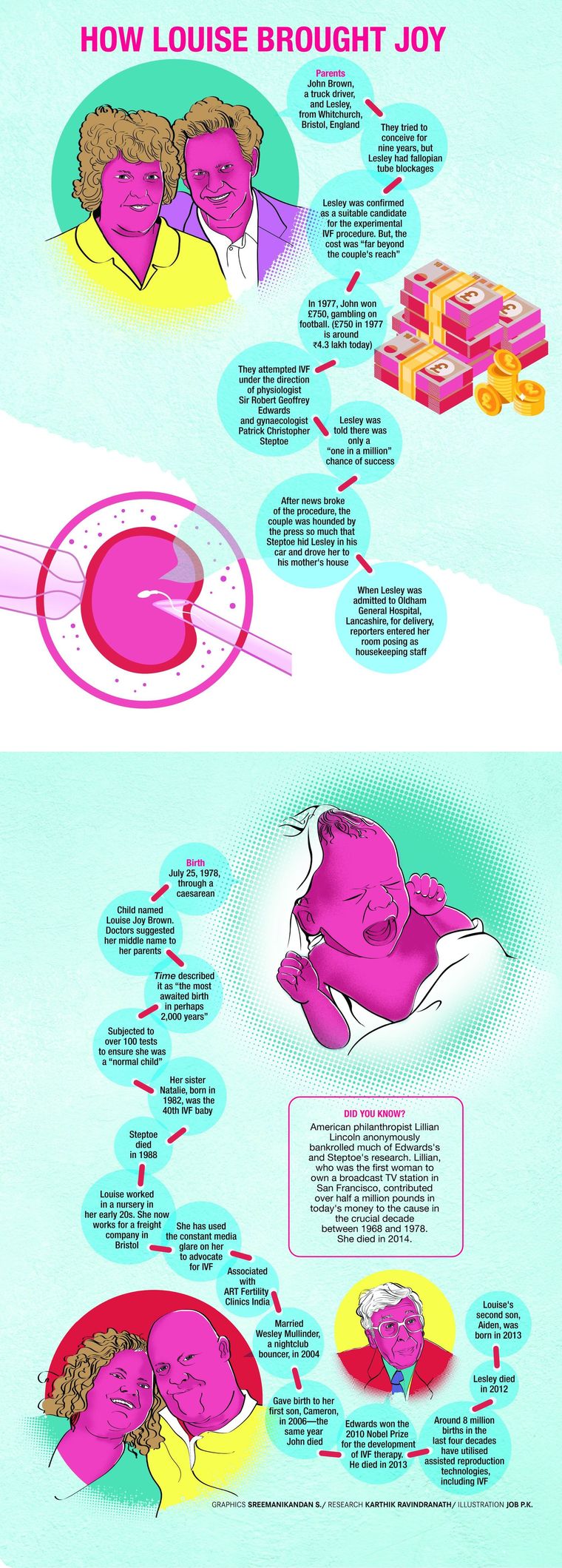

Louise was a child of perseverance and relentless hope. Her parents—Gilbert John Brown, a truck driver, and Lesley—desperately wanted a baby. The couple, who lived in Whitchurch, England, tried to conceive for nine years without success. Lesley had fallopian tube blockages that made natural conception impossible. She had undergone failed operations in the past to clear her blocked tubes and was prepared to “put up with anything” to have a baby.

On November 10, 1978, the couple underwent a procedure, wherein a mature egg extracted from one of Lesley’s ovaries was fused with John’s sperm in a laboratory under the direction of physiologist Sir Robert Geoffrey Edwards and gynaecologist Patrick Christopher Steptoe. Lesley was warned that there was only a “one in a million” chance of having a baby, but she clung to hope.

The egg was fertilised and divided into two, four and then eight cells. Lesley got pregnant after the eight-celled embryo was implanted in her womb. Being the first woman to have conceived via in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and have a pregnancy that went beyond a few weeks, Lesley attracted a lot of media attention. Edwards and Steptoe found it hard to shield her from the media frenzy. She was hounded by the press so much that Steptoe hid her in his car and drove her to his mother’s place in Lincoln. Later, when Lesley was admitted to Oldham hospital for delivery, reporters entered her room posing as housekeeping staff.

Louise ‘Joy’ Brown, weighing five pounds 12 ounces, was born by C-section at 11.47pm on July 25, 1978. The ‘Joy’ in her name was a suggestion from the two doctors. Her birth marked a milestone in modern medical science. It was described by TIME as “the most awaited birth in perhaps 2,000 years”. The baby offered a ray of hope to millions of childless couples across the world. Until then, for women with damaged fallopian tubes, it was impossible to conceive. Edwards won the Nobel Prize in 2010 for the development of IVF therapy, considered one of the most remarkable medical breakthroughs of the 20th century. Around eight million babies have been born in the last four decades through assisted reproduction technologies, including IVF.

Louise realised she was an IVF baby only when she started going to school. Lesley showed her a video footage of her birth. IVF was unheard of in those days and people were curious about her unique birth. She had always been big-bodied and some would ask her how she managed to fit in the test tube.

The Browns were in the spotlight for many years after Louise’s birth. They were criticised for allowing the doctors to film the birth. Soon after Louise’s birth, Lesley received a post bag full of letters splattered in red. Once, she received a box from the US that contained a broken test tube and a plastic foetus. Louise defended her mother, saying that letting the doctors film the birth was an act of gratitude for her.

Things were no different for Edwards and Steptoe. They had a hard time breaking the taboo and stereotypes around IVF. The idea of fertilising an egg outside the body has always been controversial. The first such successful experiment was done at Boston in 1944 by Miriam Menkin, essentially a scientist at heart and mind but often relegated to a lab technician or research assistant to the better-known fertility specialist and contraceptive pill co-developer John Rock. The research got derailed with Menkin’s move to North Carolina, where IVF was considered scandalous, following her husband’s job loss. But it was Menkin’s initial research that eventually led to Louise’s birth through IVF.

Edwards, Steptoe and nurse Jean Purdy, whose contribution was forgotten till recently, feared criticism from the church and the public and they kept their work under wraps. Only five of the 282 women who underwent IVF could get clinically pregnant and none of them had delivered a live baby. Many embryos died during the process. Unsurprisingly, the medical community refused them support for research. The UK Medical Research Council feared children born through IVF would run a risk of fatal abnormalities. IVF children, Louise said, are no different from normal children. “The only difference is the process of conception,” she said. “It is impossible to distinguish between an IVF baby and other children born naturally.”

John and Lesley went for IVF again and had a second child—Natalie. The couple wanted a third child, but their attempts failed. Natalie was the 40th child to be born through IVF. She became the first IVF child to conceive naturally, easing concerns that women born through IVF cannot conceive naturally. Natalie now has five children.For the Browns, IVF changed their life in more ways than one. Lesley was John’s second wife; he had two daughters from a previous marriage. John and Lesley, who stayed in an abandoned railway carriage on the first night of their elopement, had a hard life. Homeless, penniless and unemployed, they struggled a lot until John got a job as a bus conductor.

Infertility was an extremely frustrating experience for Lesley. In an interview to Daily Mail later, she said, “You feel you are not the same as ordinary wives. You don’t feel normal. You feel you are not a real woman. I said to John, ‘Go and find a proper wife.’”

The couple couldn’t afford IVF until 1977, when John won £750, by betting on the outcome of a football match. That helped him pay for the IVF treatment.After Louise was born, the Browns earned money by doing exclusives. Louise’s birth was reported exclusively by Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers Ltd, the parent company of Daily Mail, secured exclusive rights to the story and pictures reportedly by paying $600,000. Lesley and John stayed positive amid the negativity that was directed at them. They went on speaking assignments around the world as advocates for IVF.

Louise now lives in Oldham with her husband Wesley Mullinder, a nightclub bouncer. Interestingly, Mullinder first met Louise when she was just a few days old. Eight-year-old Mullinder lived across the street from the Browns and was among the crowd gathered to see the extraordinary baby. The duo later met when Louise was 24. Two years later, they were married. They have two boys—Cameron and Aiden. Cameron is 14 and has just begun with his General Certificate of Secondary Education exams; he will be applying for college in another two years. Aiden turned eight this August.

All her life, Louise received media attention. And now she is consciously using the media glare on her to break the stigma associated with infertility and IVF treatments. “Couples suffer through a lot of emotional and psychological stress. I think no couple should be deprived of parenthood,” said Louise, who has shared the story of her extraordinary birth and its impact on her life in her memoir My Life As The World’s First Test Tube Baby. “Through my association with ART Fertility Clinics India, I will be working towards the mission of making IVF the wise choice of treatment, enabling couples to realise the dream of parenthood. Another purpose is to assert that all those who need IVF should have access to it.”

IVF has come a long way. Scientists now pin their hopes on IVG (in vitro gametogenesis), which could make it possible to produce babies from skin cells. IVG seemed promising when tested in mice. In 2016, a group of researchers in Japan created embryos using skin cells from mice. The embryos were

implanted, and eight healthy mice were born.

Scientists are now exploring the possibility of making human babies in the lab using skin cells. Imagine a couple wanting to have a baby walking in to a lab to give their skin biopsy samples. The cells from these samples will be transformed into stem cells, which, in turn, will be reprogrammed into sperms and eggs. The process involves creating embryos outside the womb and then transferring them into the woman’s womb for implantation, as in IVF. IVG holds much promise for people who cannot conceive naturally, especially menopausal women, gay and lesbian couples and men with abnormal sperm function or low sperm production.

Dr Henry T. Greely, author of The End of Sex and the Future of Human Reproduction, said that in future, sex will no longer be a popular means of reproduction for people in developed countries. People will continue to have sex. But those who want to have a baby would prefer to go to a lab, said the Stanford professor of law and genetics. IVG for humans will be a reality within our lifetime, said Greely.

Every woman has the right to have a child, said Louise. “Treatment for fertility problems is a right that should be made available to all women,” she said. IVF not only creates a child, but a family, she added. Despite her extraordinary birth, Louise lives an ordinary life. She worked in a nursery in her early 20s. Currently, she works for a freight company in Bristol. Her days begin with planning meetings with her team at National Fertility Society; her evenings are dedicated to her family. Home means a lot to Louise, who was a much loved and much longed for child. Her mother had carefully kept everything concerned with her birth, from hospital appointment cards and correspondence to letters from journalists and well-wishers and even a movie script by Carl Foreman, Oscar-winning Hollywood film producer. Louise donated them to the Bristol Archives. Among them is a letter from Edwards to Lesley, dated December 6, 1977, which reads:

Dear Mrs Brown,

Just a short note to let you know that the early results on your blood and urine samples are very encouraging, and indicate that you might be in early pregnancy.

So please take things quietly—no skiing, climbing, or anything too strenuous including Xmas shopping!

If you should wish to get in touch with me for any reason before seeing Mr Steptoe next week, my laboratory number is 0223 65069, and my home number is 0223 54019. Best wishes.

Yours sincerely,

Dr R.G. Edwards

All these mementos were found in Lesley’s wardrobe following her death. She died due to complications of a gallbladder infection on June 6, 2012. She never regretted her choices.