Reenu Jennifer had a bad cold recently. “I had symptoms like sore throat, headache and stuffy nose, which made it hard for me to breathe,’’ recalls Jennifer, a teacher at St Joseph’s Boys High School, Bengaluru. She was unable to do her daily chores and was grumpy and cranky. “Due to the current pandemic situation, I chose to work from home until I recovered. I didn’t want to expose others around me to the infection,’’ she says.

Homebound, Jennifer kept gargling and taking steam inhalation. She also tried home remedies like honey ginger tea, which helped ease her symptoms.

Jennifer wonders why medical science is still not able to find a cure for common cold, the most common infectious disease among humans. Dr Swati Rajagopal, consultant, infectious diseases and travel medicine, Aster CMI Hospital, Bengaluru, has the answer. “Since common colds are caused by rhinoviruses, the challenge is the number of circulating strains or types of the virus. There are at least 160 aero types or strains of the virus, so unfortunately we do not have one master key to cure the virus. It is virtually impossible to create one vaccine or one drug against the 160 types.’’

In the future, we can successfully evolve a method of targeting the immune response against the structure common to all subtypes, says Rajagopal. “That is when we can offer protection against all the subtypes,” she says.

Infections have marched in lockstep with us in our race to modernity. The world is still reeling under a pandemic, and Omicron, the new Covid-19 variant, has cast a dark shadow on our hopes of returning to a normal life. “The vaccine is short-lived. The antibodies and protection do not last long and hence you have to keep taking the vaccine. Also, infection with the virus causes long-term problems in 40 per cent of those who got even a mild infection. We are going to live with this for a long time,’’ says a top Emory virologist. “The current viruses are not vaccine-escape mutants. They are coming. I hope I am wrong.’’

India has a disproportionately high burden of infectious diseases. Common infections include upper respiratory infections, influenza, diarrhoea, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, worm infestations, infections affecting the skin and soft tissues like boils and abscesses, tuberculosis, dengue, malaria, chikungunya, typhoid fever and HIV/AIDS. It is estimated that drug-resistant infections will result in 10 million deaths a year worldwide by 2050, a significant portion of which will occur in India. Drug-resistant tuberculosis has already been a major public health concern in the country, despite the government’s efforts to eradicate TB by 2025.

Veteran virologist Dr Jacob John is appalled with the way India deals with its infectious diseases. “Take, for instance, TB. How many people have TB in the country? WHO tells us the numbers. If you ask any doctor, he will say the numbers given by WHO are an underestimation. We don’t have a policy to control cholera or typhoid fever. India is home to infectious diseases and yet we don’t have a policy,’’ he says. “We are very tolerant. We tolerate filth, plastic, bacteria, viruses and diseases.’’

In the west, if a person is infected with cholera, they make sure the system is cleared to control the infection, says John. “A patient with an infectious disease receives the same kind of treatment in India and the west. However, there is a huge difference in the way the public health system works. In European countries, that one patient will result in a community investigation. They trace the origins of the outbreak and take necessary measures to reduce the transmission. On the other hand, in India we will add one statistic point and move on,’’ says John, who describes himself as an unwelcome virologist who brings up inconvenient facts.

The pandemic has changed everything. The changes in our susceptibility to infections are evident in the outpatient department of our hospitals. “People at large are using masks. As a result, respiratory infections have come down,’’ observes Dr Mahendra Dadke, head of department, internal medicine, Jupiter Hospital, Pune. “Usually the paediatric OPD is full of respiratory infections. But as schools were closed, the incidence of those infections came down.”

But we can’t breathe easy, owing to Omicron. “Omicron is a mutating virus. It is an unusual mutational variant, having many mutations in one variant,” says John. “It is a leapfrog mutation, not step by step mutation. The mutations look as if the variant had been mutating for a long time.” The virus now is more virulent and spreads faster. Also, it escapes previous immunity.

People who get Covid-19 are found to be more prone to other infections like fungal infection. The high incidence of mucormycosis in the country is attributed to the rampant use of steroids in Covid-19 patients. Moreover, Covid-19 affects pancreatic beta cells. So the incidence of diabetes or high blood sugar has gone up in the population, which, in turn, causes other infections like urinary tract infection and skin infections. “Sugar is a good medium for bacteria to grow,” explains Dadke.

Even something innocuous as a spinach or lettuce salad can sometimes lead to infections. Eating unwashed or badly or improperly cooked food can cause neurocysticercosis, an infection of the brain and spinal cord. “Though the infection was considered to be common among non-vegetarians, especially those who eat pork, later we came to know that it is more commonly seen among vegetarians. That is possibly due to the use of vegetables that are contaminated with the eggs of tapeworms,’’ says Dr P. Satish Chandra, adviser and senior consultant, neurology, Apollo Hospitals, Jayanagar, Bengaluru. These eggs will get into the body through consumption of unhygienic food. It travels through the blood and could get lodged anywhere in the body. If it lodges in the brain or spinal cord, it is called neurocysticercosis, explains Chandra, who is also former director and vice chancellor, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru.

Neurocysticercosis affects the nervous system in different ways and the manifestations may vary. The commonest manifestation is seizure. If it occurs in the spinal cord, the patient may experience weakness in limbs.

But that is not as common as, say, urinary tract infections (UTIs) that affect both men and women. Women are at greater risk of UTIs than men. A recent study published in Therapeutic Advances in Urology says that 50-60 per cent of women experience UTIs at least once in their lifetime.

Do not ignore symptoms of UTIs, warns Dr Prathima Reddy, director, lead obstetrician and gynaecologist at Sparsh Superspeciality Hospital for Women and Children, Bengaluru. UTI, if left untreated, could lead to inflammation of the kidneys and septic shock, a potentially fatal medical condition.

Bond girl Tanya Roberts, fondly remembered for her performance in A View to A Kill as well as Charlie’s Angels died of a UTI in early 2021. Roberts developed sepsis after the UTI. The infection had spread to her “kidney, liver, gallbladder, and then bloodstream”, leading to her death.

In pregnant women, UTI could result in complications that can affect both the mother and the baby. “UTI causes growth restriction and reduced weight of the baby. People often resort to self-medication for UTI, which in turn can lead to health complications. Most frequently, we find that people start antibiotics by themselves,’’ says Reddy.

It is always better to see a doctor and get a urine culture and sensitivity test done, she says. “The urine culture report comes back to us in about three days,” says Reddy. “Meanwhile, if the symptoms are really bad, we start the patient on antibiotics and change the medicines later once we get the reports. The urine culture test will help the doctor know whether the antibiotics prescribed for the patient are the right ones. UTI can affect women of all ages—teenagers, middle-aged, pregnant and post-menopausal women.”

Symptoms of UTI include a burning sensation and pain while passing urine, increased frequency of urination and presence of blood in urine. The patient may also experience chills with a fever. “If any of these symptoms start, drink plenty of water, see a doctor, get a urine test done and start an antibiotic prescribed by them,” says Reddy.

Some infectious diseases like malaria and typhoid, though, share similar symptoms, making diagnosis harder. Manu Leen from Kochi had symptoms like fever, headache, nausea and diarrhoea. As her condition worsened, she was hospitalised. Malaria was suspected, and she was given anti-malarials. The test results took too long, she recalls.

A diagnosis of typhoid was confirmed later. “I was going through tremendous pain—severe headache and body pain,” says Leen. “I would scream in pain and my family thought I wouldn’t survive. I couldn’t eat anything.”

Leen survived the illness, but the misdiagnosis, medications and prolonged hospital stay took a heavy toll on her health.

She had no relapse of typhoid, but she lost 20kg and had excessive hair fall. She also had persistent body aches that lasted around three months.

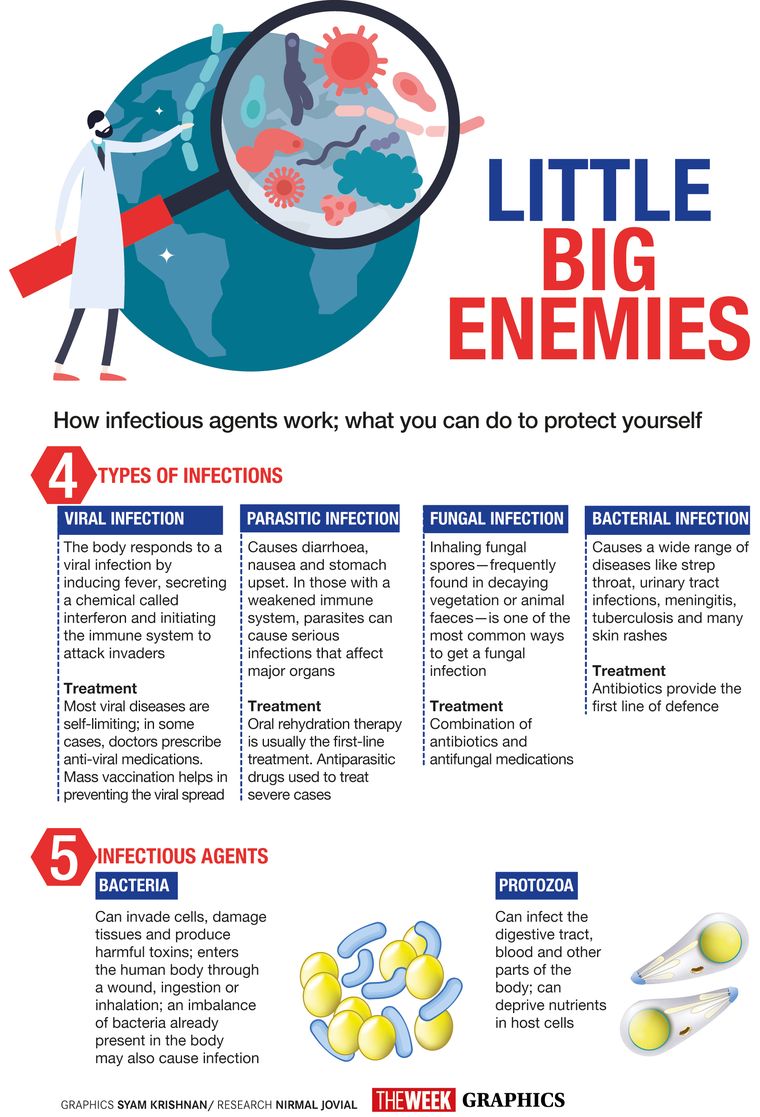

Fever is a common symptom of most infections. It may or may not be associated with other manifestations such as cough, cold, diarrhoea, skin rash and body ache. Most infections are viral and are self-limiting. “Hence patients can take symptomatic therapy for the first 2-3 days with antipyretics, cough syrups, oral rehydration solutions (but never antibiotics) and seek medical help if they are not better by third or fourth day,’’ explains Dr Tanu Singhal, consultant, paediatrics and infectious diseases, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, Mumbai. “However, if there are risk factors such as extremes of age (very young or very old), immunocompromised state, underlying diseases or excessive fatigue, weakness, dizziness, lethargy, breathing difficulty, low urine output, persistent headache and vomiting, they should report to emergency services immediately.”

Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and radiation are more susceptible to infections because of their immunocompromised state, says Dr B.S. Ajaikumar, chairman and CEO, HCG Group of Hospitals, Bengaluru. “They may have infections without any fever,” he says. “Their body's ability to fight infections is lower as their immunity levels are low. We usually do what we call immunity scoring. Based on that, we decide which patients are likely to get infections and we take lot of preventive measures, apart from normal hand washing and masking. We also make sure these patients get some oral antibiotics before we administer them chemotherapy.” The infection rate is higher in patients undergoing chemotherapy than radiation.

Infections come through the water we drink, too. Parvathy, 37, from Thurputhallu, a coastal village in west Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh, earns a living by cleaning and selling the fish her husband catches.

One day, she complained of fever, continuous vomiting and diarrhoea. Medical investigations by the village health care provider revealed that she had jaundice. “The likely cause was the water that she had been consuming,’’ says Dr Swati Subodh, cofounder of 1M1B foundation. The foundation’s Project Auxilia focuses on health care of fishermen in rural Andhra Pradesh.

In Thurputhallu, clean water is still a luxury many cannot afford. Fetching water from a public tap has been part of Parvathy’s daily grind ever since she got married. Living on land surrounded by the sea, she always knew the water in her village was not fit for drinking. However, like most women in her village, she would use it for drinking and cooking. The smell and purity of the water bothered her, but she had no access to other sources.

Parvathy’s long road to recovery took a heavy toll on the family’s income. She was not able to work for a month.

“Since then Parvathy boils her water, as much as possible,” says Subodh. “However, the additional fuel cost incurred for boiling the water does not make this a likely long-term solution to her.”

Infections add to rural India’s health woes. Water-borne diseases like cholera, jaundice, diarrhoea and hepatitis are high in coastal communities of west Godavari, says Subodh. Project Auxilia encourages fishermen to use cost-effective charcoal-based water filters.

Infections don’t spare newborns either. Preterm or low birth weight newborns are at increased risk of infections. Pneumonia, sepsis, tetanus and diarrhoea are some of the leading causes of neonatal deaths in India. Infection in babies born less than 72 hours ago is usually caused by the maternal genital tract, says Dr Amit Gupta, chief neonatologist and paediatrician, Motherhood Hospital, Noida.

“Genital tract infection is common during pregnancy and can result in neonatal infection,” he says. “Newborns can also get infected owing to contaminated hospital surroundings. Unhygienic hands play a major role in community-acquired infections.”

Fortunately, breast milk comes to the rescue of infants as it contains antibodies that can fight infection. “Antibodies are present in high amounts in colostrum, the first milk that comes out of the breasts after birth,” says Gupta. “Breast milk is also said to provide other essentials like proteins, fats, sugars and contains white blood cells that work to fight infection in many different ways. It is also said that breastfeeding sets the stage for a protective and balanced immune system that helps recognise and fight infections and other diseases even after breastfeeding ends.’’

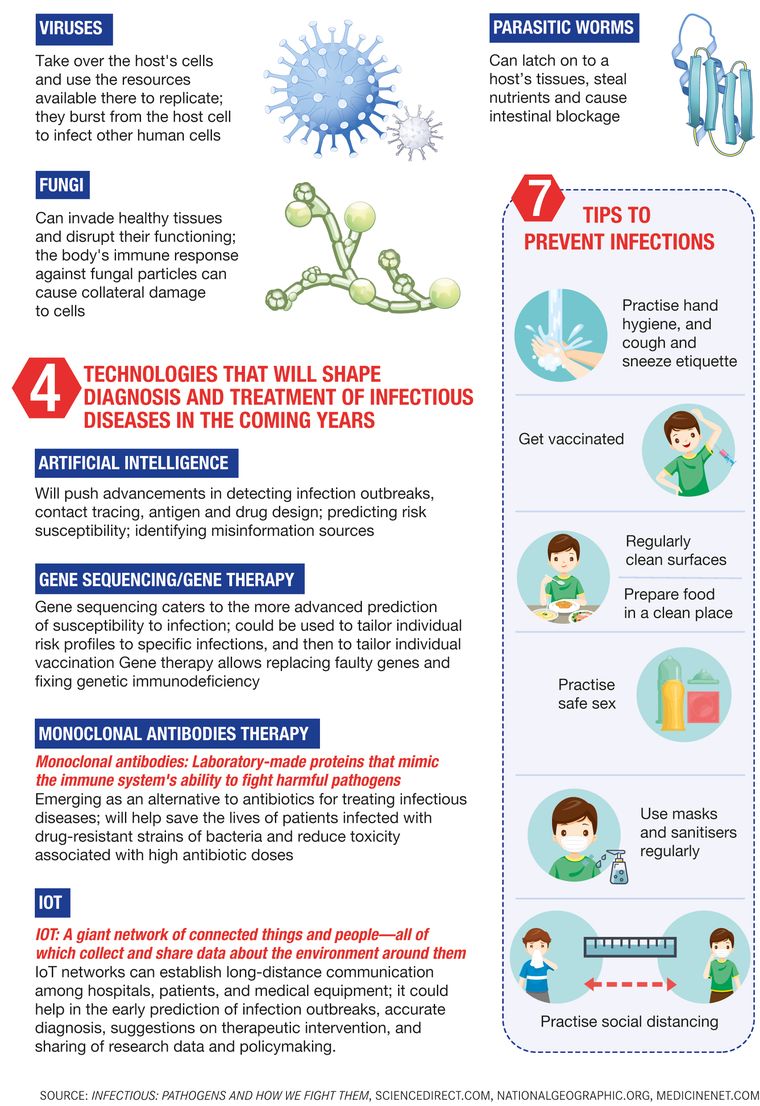

Moreover, advancements in diagnostics and treatment offer much hope. For tackling infections, the need usually is quick diagnosis and accurate treatment, which, in general, reduces mortality, says Dr Neha Mishra, consultant, infectious diseases, Manipal Hospital, Old Airport Road, Bengaluru.

“If we look at bacterial infections, it used to take as long as 72 hours to know the cultures (isolating bacteria in labs),” she says. Now, it is possible to not only classify the type of organism but also the type of mutation in much lesser time, thereby enabling a quick decision on the therapy to be provided. “Inventions like MALDI-TOF and BACTEC have made speciation easy and quick, while modalities like Carba gene XPERT give us an answer regarding mutation within an hour’s time,” she says.

Techniques like PCR testing have made it easier to diagnose viral infection and that too on any type of sample, be it blood, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid or urine, says Mishra. “Such PCR techniques have been used to diagnose bacterial and fungal infections as well,” she adds.

Not only diagnostics, the treatments have also taken a leap. “For instance, in HIV, the type of drugs available—dolutegravir, bictegravir—now has made the disease easily manageable,” says Mishra. “The good news is that such changes have been implemented even in government programmes, making these drugs more accessible and available to all. These changes have taken HIV/AIDS from a universally fatal disease to a chronic health care issue.”

A lot of advancements have taken place in treatments for lung infections, too, especially tuberculosis. Thirteen-year-old Shourya Akshata Mangaonkar from Mumbai experienced severe stomach ache during Diwali. “We discovered that she had TB,’’ recalls Akshata Mangaonkar, her mother. It was a highly complex and critical case, she recalls. Mangaonkar was treated at Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital, Mumbai. She is now recuperating at home.

Earlier patients with TB used to be given blanket therapy or empirical medication. “We are getting the reports faster now,” says Dr Arvind Kate, chest physician and pulmonologist, Zen Multispeciality Hospital, Mumbai. “In the last two years, there are newer diagnostic modalities like respiratory BioFire that are available. They have made diagnosis faster and more accurate. We are more targeted now in terms of our therapies. We are more selective in our antibiotics. This helps to prevent antibiotic resistance. It helps save costs, too.”

Giant strides have been made in biomarker science, too. “Biomarkers help us understand in what direction patients are going,” says Kate. “Some antibiotics are very costly and patients end up spending Rs10,000-Rs15,000 a day just on antibiotics. With biomarkers, we know whether the antibiotics work and if the infection is under control.”

Abhishek Salagre, 29, a chartered accountant from Mumbai would vouch for that. He was diagnosed with TB on his 24th birthday. “I was doing my chartered accountancy course then. My schedule was so hectic that I barely had time to eat,” he says. “I would often skip my lunch and dinner and my immunity came down drastically.’’

When TB manifested as chest pain, Salagre consulted a doctor. It was found that both his lungs had been affected. Salagre had a hard time managing his studies and fighting the potentially serious infection. To add to that, his treatment was delayed as the doctor was using traditional methods. “I took the TB medicine for 18 months. Then I met Kate and in three months, my treatment got completed,’’ says Salagre, who is getting married to his girlfriend.

Antimicrobial resistance is a huge challenge in the treatment of TB. Bacteria and bugs which used to be easily treated with a certain level of anti-bacterials are now showing tremendous resistance to them. This is the world’s major challenge today, especially in ICUs, says Dr Rohit Shetty, consultant, cornea and refractive surgery and vice chairman, Narayana Nethralaya, Bengaluru. “We use the antibiotics so much that the bacteria become tolerant to them,” he says. “A huge chunk of antibacterials of the 1980s and 1990s are no longer sensitive to a lot of bacteria. We have to keep building new drugs. After a few years, the same drug won’t work because of the antibiotic abuse.”

There has been a rise in multi-drug resistance over the last 10 years. “Bacteria that are resistant to certain types of antibiotics make treatment of TB all the more challenging. New medications are being introduced by the government to tackle this problem,’’ says Kate. Antibiotic misuse is common in outpatient practice, which contributes to antimicrobial resistance.

Jael Varma has never taken antibiotics. The Bengalurean hardly falls sick. “I eat basic homemade food. I never take tablets unless it is a dire necessity,” says the poet. “I stay away from toxicity (both situations and people) and I always drink hot water.” Dancing and practising mindfulness keep her happy and healthy. Varma says our body is supremely intelligent. “It always tells us what is wrong,” she says. “All you have to do is pause and listen.”

For Bengaluru-based media professional Barkha Chawla, science and nature go hand in hand. That is why she has no qualms in letting her two-year-old—Jeeana—play in the sand. Chawla believes that a little exposure to the environment helps children build a strong immune system. “I always allow her to go out in the nature,” she says. But she also abides by the ‘prevention is better than cure’ adage, and so adds that if there is enough scientific proof that “a vaccine will save my child from an array of infections and life-threatening diseases, I will immunise my child without a second thought”.

Vaccines are the most powerful weapons in our arsenal in the fight against infectious diseases. Vaccine hesitancy, says John, is a major public health challenge, especially in rural India. “People don’t trust the system,” he says. “They think the government is covering up adverse reactions. The truth is we don’t have a system to monitor adverse reaction. It is a systemic failure.’’

In the fight against infections, more dramatic than treatment advances are advances in prevention of infections through vaccination, says Singhal. “Small pox is the most striking example. Apart from smallpox, the incidence of polio, diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough and measles have declined dramatically due to widespread immunisation,” he says. “On the flip side, we still await effective vaccines against tuberculosis, malaria and dengue.”

We live in a world full of microbes. Pathogenic microbes are present in the air we breathe and the food we eat. Germs lurk in bathroom light switches, refrigerators, microwave handles and stove knobs. Public restrooms are breeding grounds for E. coli, streptococcus, hepatitis A virus and the common cold virus. Cash and pillows have more germs than we think. If you are reading this story on your phone, don’t forget to wash your hands before you snack. A study conducted by Insurance2Go, a gadget insurance provider in England, shows that smartphone screens have three times more germs than a toilet seat.

Getting rid of germs in our environment is an insurmountable task though. All we can do is maintain hygiene, learn to coexist with bugs and protect our body against infections.