Since March 2022, Canadian couple Edith Lemay and Sebastian Pelletier and their four children have been on the move, taking in sights and sounds as they tour the world. From the dunes in Namibia and valleys in Kilimanjaro to dancing with the Maasai tribals in Tanzania, hot-air ballooning in Turkey and dressing up as a nomadic reindeer herder in Mongolia, it has not been merely a travel for leisure but one with a purpose. For Lemay and Pelletier, this journey is all about creating visual memories for their children. Memories―snapshots of our lived experience―are essential as they help connect our past with our present and prepare us for the future. And, Lemay and Pelletier are hoping these visual memories, carefully curated by them, may come handy for the children when they face the dark days ahead.

“Three of my children have retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a genetic disease without any cure as of now,” Lemay told THE WEEK over a Zoom call from Thailand. “Our eldest kid, Mia, is 11 now. Then there is Leo, who is nine, Colin, who is seven, and Laurent, who is five. Leo is the only one who is not affected by RP.”

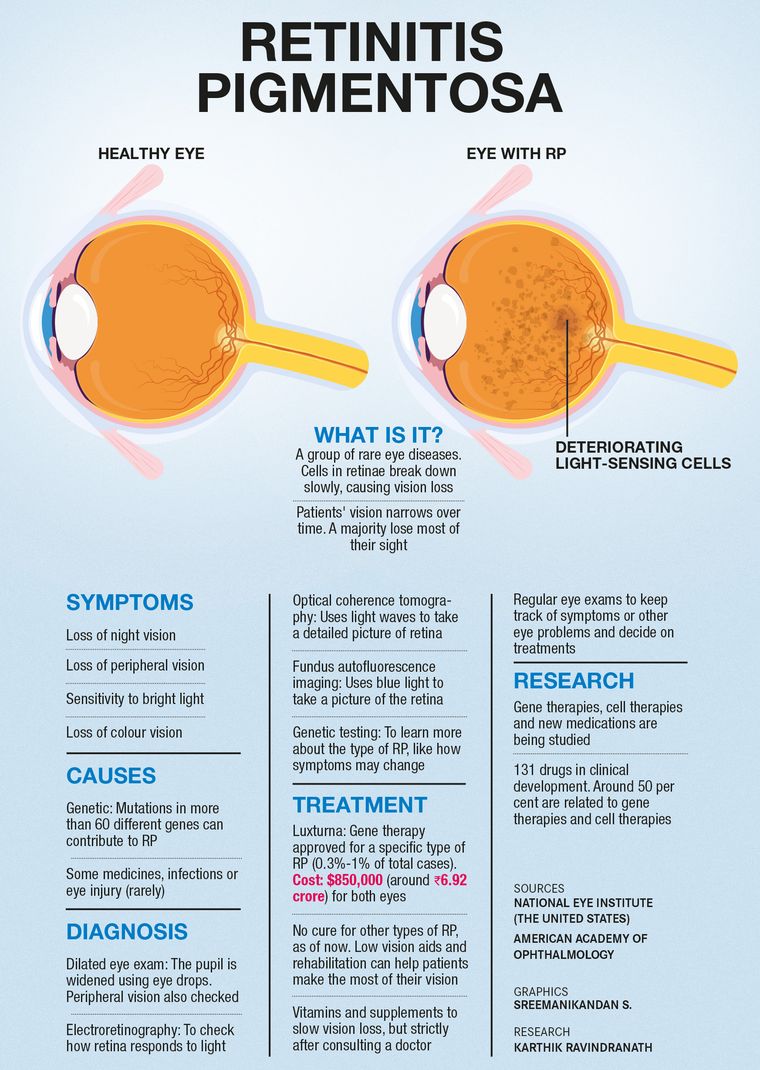

Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of rare eye diseases that affect the retina. It makes cells in the retina break down slowly over time, causing vision loss. It is a disease that people are born with. Symptoms usually start in childhood, and most people eventually lose most of their vision. The retinal cells called rods and cones die in patients with RP because of a mutation in one of their genes. In a majority of cases, rods―mainly located in the outer regions of the retina and responsible for peripheral and night vision―die down first. When more centrally located conduits also get affected, the patient with RP would face loss of colour perception and central (reading) vision, too.

Lemay and Pelletier observed the first symptoms of RP in Mia when she was just three. “We found something was wrong with Mia’s night vision,” said Lemay. “We observed that she was bumping into walls and furniture in dim light. We did not know what was happening.” As the problem persisted, the couple took Mia to an optometrist. Nothing specific was detected. On the optometrist’s suggestion, they took Mia to an ophthalmologist. The ophthalmologist, too, could not spot what was wrong, but asked the couple to get a gene test. The initial results of the gene test did not reveal any issue in Mia. “But then there was this research that was going on,” said Lemay. “They did this whole genome [testing] for Mia, Sebastian and me. It took two years before we got the results, and we came to know that Mia has this condition, that she is slowly losing her vision.”

The final test results came when Mia was 7. The genome test showed that the PDE6B gene was defective in Mia―the gene provides instructions for making a protein that is one part of a protein complex found in the rod. Soon, Lemay and Pelletier observed night vision issues in Colin and Laurent, too. “My children are slowly losing their vision from the outside towards the inside,” said Lemay. “So, in the end, their sight will be like looking through a straw. Their field of vision is shrinking over time.”

The couple’s initial reactions to Mia’s test result were “shock and disbelief”. “Because when you have kids, you just have an idea of how their future is going to look like and what is their life going to look like. But all of a sudden, you just need to rethink all that,” said Lemay. “At first, we thought there was a mistake. Then you get angry, you are looking for an answer everywhere. You get sad. But after a while we started to accept the reality.”

Some people with RP lose their vision more quickly than others. Eventually, most people with RP lose their side and central vision. The couple cannot tell for now how long it would take their children to lose vision completely. “It can be different for all my three children,” said Lemay. “It seems to be pretty slow. So they are expected to be totally blind by mid-life. But there is a possibility that they will be able to keep a little part of their field of vision.” Right now, their daytime vision is super good, said Lemay. “Their field of vision is still good. But their night vision is gone,” she said. “When the light is dim, they cannot see anything. So, we have to use flashlights when we walk outside in the dark.”

Over the years, Mia has developed a sensitivity to bright light, too, said Lemay. “Whenever she is out in a sunny setting, she needs to wear a hat,” she said. “Because her eyes start watering and also she has difficulty adapting.” Her eyes take some time to adjust if she moves inside from bright outdoors.

By the age of 40, most patients with RP reach a level at which they can be classified as ‘legally blind’. With reduced visual acuity and a narrowing field of vision, performing daily activities may become difficult. Patients with RP may also experience a loss of independence. This may lead to anxiety and depression and reduced quality of life.

But Lemay is not one to brood when faced with a problem. When she realised that her children were slowly going blind, she started thinking about what she could do to help them cope. “I first thought about providing Mia with some tools that would help her in the future,” recalled Lemay. “I also thought that she could learn Braille at school.” But the specialist at school told Lemay that Mia’s current vision was way too good for her to learn Braille properly. Instead, the specialist advised Lemay to fill her visual memory, so that Mia will have a mental image to refer to even if she loses her vision. “That is when it clicked,” said Lemay. “Instead of showing an image of a giraffe or an elephant on a book or TV, let’s go and show real elephants and giraffes to our children.” Thus started the family’s planning for a world tour.

The original idea was to start the journey from their home in the Quebec province of Canada by July 2020, but then the pandemic happened. “In 2020, we wanted to cross Russia, take the Trans-Siberian [rail], cross Mongolia and then go to China,” recalled Lemay. “But the pandemic made us rework our itinerary so many times. In the end, we just left without any itinerary. We looked at which countries were open. Africa was open then. So, we booked tickets to Namibia and finally left [Canada] in March 2022.”

Lemay, who used to work in health care logistics, and Pelletier, who was working in finance, resigned from their jobs before the trip. While they had saved for the trip, their savings got a boost when the company Pelletier worked for and had shares in was bought. The family has already touched three continents and 12 countries on this trip.

The travel plan has accommodated things on the children’s bucket list. “Mia loves horses, so she was excited about horseback riding in Mongolia,” said Lemay. “Once she did the ride, she became so emotional.” Leo loved the animals in Africa and Colin found the train journeys in Tanzania special. An experience that excited both the children and the parents alike was the hot air balloon ride in Cappadocia, Turkey. It has become Laurent’s favourite memory so far. “We got there before the sunrise and walked in really dark fields [with the flashlights on],” recounted Lemay. “And, all of a sudden, we saw these giant hot air balloons taking off. It was like giant lanterns soaring all around us. We told the kids that we would go see them take off, but cannot afford to get in them. They were okay with it. They were excited to see them take off. But when we told them that we were actually going in it, they were in heaven. So, we got in the hot air balloon, taking off slowly as the sun was rising from the horizon. Along with us were hundreds of other hot air balloons. The colour was all pinkish and it was just amazing.”

The family spent their Christmas on a remote island in Cambodia. A few of their friends from Quebec flew to the island to celebrate with them. There, they made a Christmas tree with a palm tree branch and put some lights on it.

But the day they would love to celebrate the most is the day when medical science finds a cure for RP. The advancements in gene and cell therapies give hope to lakhs of families. According to a research paper published in the journal Clinical Ophthalmology in 2022, Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl) is the only approved therapy for RP as of now. But it is only authorised for treatment of a small subpopulation of patients that has the mutation in the RPE65 gene. It is estimated that those with defective RPE65 genes represent only 0.3 per cent of the total RP cases. So, most patients are limited to the best supportive care, including reliance on vitamin supplements, protection from sunlight and visual aids.

The research paper says that 131 drugs are in all stages of clinical development for RP. Around 50 per cent of these drugs are related to gene therapies and cell therapies. Gene therapies target non-functional photoreceptors, making them more suitable for early to mid-stage disease. In gene therapy, the idea is to treat the disease and restore vision by introducing healthy genetic material into cells to produce a functional protein or compensate for a diseased gene. Gene therapies are tailored to specific gene mutations, increasing their effectiveness and allowing for personalised treatment. However, in the advanced stages of the disease, conventional gene therapy may not be effective as the target cells will have largely degenerated. Early referral, diagnosis and gene testing are crucial for patients with RP to ensure that they receive treatment within the limited window for a successful gene therapy.

In contrast, cell therapies can be applied throughout the progression of the disease, as they are independent of the presence of photoreceptors. In cell therapies, there are two main therapeutic goals: either to preserve and restore the function of dysfunctional cells or directly replace dead or dysfunctional cells with healthy ones. Around 13 gene therapy drugs and two cell therapy drugs are in the later stages of development.

Though these developments are happening in labs, Lemay said that she was preparing her children for a worst-case scenario―a future where no cure is developed for their defective genes. She explained that the trip is in a way helping in that preparation. “One thing that they are going to lose is that wide field of vision, so we are trying to stay in nature where [they get a chance to experience] the field of vision in a wide, open space,” she said.

In the process, Lemay realised that children live in the moment. “They do not do this trip with the urgency to [make or] keep memories. They are just enjoying the moment,” she said. “You want them to look at certain beautiful structures or temples, but they may see a nice and cute stray cat and for them, that is going to be the most beautiful thing over there. And, that is okay. What they think is beautiful is as important as what we think is beautiful.”

Resilience is another thing that Lemay expects her children to develop through this journey. “Because, with RP, what happens is that they are going to lose vision, but slowly. So, it is going to be constant readjustment and adaptation in their lives,” she said. “For example, they may be able to drive for some time, but after a while they are going to have to let that go. And, they may require to use a cane or a guide dog. There is going to be falling, and they have to get back up and find a solution.”

The family has kept the trip low budget, avoiding big hotels and first-class flights. “When you travel like that, it can get uncomfortable,” said Lemay. “We may face hot weather; we can be hungry or tired. So, children need to adapt all the time. I want them to learn that a bad situation will eventually end, and things will get better.” For instance, they had an uncomfortable experience while travelling from Zambia to Tanzania. They were supposed to take a train from Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, but a bridge had collapsed and trains had stopped running. So, they took a bus. “It was supposed to be a 12-hour journey, but it ended up being a 16-hour ride,” recalled Lemay. “There were just three stops in that journey. And, one of the stops was a field. We were asked to go to the field [as there were no toilets] and come back within five minutes. And, the kids said it was the worst bus ride of their life. And, I think they will remember it for a very long time.”

The family is currently in Laos. Though the children love travelling, the family plans to be back in Quebec before the school year is over (in June) so that Mia can say goodbye to her friends before she starts high school (grade 7). Those are also precious moments that Mia wants her brain’s memory card to store.

LET'S GO!

This is the beginning of the adventure, we're diving in! We have butterflies in our stomachs, weak legs, but we're so excited! We're sleeping in Toronto tonight, then taking a 13-hour flight to Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), then another 5 hour 30 minute flight to Windhoek (Namibia). And we have a tight connection that we definitely don't want to miss, otherwise we'll be stuck in Ethiopia for 2 days.

IT'S TIME FOR AFRICA

Our visit to a Maasai village really impressed the children, especially Laurent. He told us he would be a Maasai when he grew up. He can't wait to be 10 years old to drink cow's blood mixed with milk because it will make him strong. The visit is well-choreographed for tourists―they dress you up, invite you to participate in a welcoming dance with the whole village, light a fire, visit a house and do archery. It is still really interesting to learn about their way of life. And their singing, dancing and jumping are truly impressive.

SUN, SAND AND SIGHT

Sossusvlei is one of the main attractions in Namibia. It is a long strip of clay and salt in the middle of spectacular red dunes. These dunes are among the highest in the world. At the end, surrounded by dunes, there is Dead Vlei, an old marsh that, cut off from its water, has turned into a tree cemetery. These sun-burned tree skeletons form a strange and contrasting spectacle with the red dunes and white ground. The best time to see the dunes is at sunrise and sunset, for the light and the play of shadows, but also because during the day, the heat is scorching. As a good tourist, we got up before dawn to climb the famous Dune 45. Well, already getting up early for my children is not a joy. Climbing a steep slope in the sand, not easy, especially at that scale. Watching a sunrise for children who are sensitive to bright light, not the best idea. And, of course, the wind joined in to make everything pleasant. In short, the first photo (above) summarises our morning well! I managed to take some good photos, but this one is definitely my favourite. Fortunately, we took it again at sunset on Dune Elim. The climb was endless with its 12 false summits, but on the descent the colours were so intense that it felt like a painting.