Love doesn’t come with a use by date. Model-actor Milind Soman, 57, would agree. He married fitness entrepreneur Ankita Konwar when he was 52 and she 26. And, he is no exception. Last year, Indian Premier League founder Lalit Modi, 59, declared his love for Sushmita Sen, 47, on social media. Then there’s former solicitor general of India Harish Salve, 67, who married London artist Caroline Brossard, 58, in 2020. All of these relationships made headlines, not necessarily for the right reasons. In a society where any divergence from a set way of life is looked down upon, such love does come with stigma and restrictions―the cost of seeking companionship and intimacy at a time when the elderly are expected to look after grandchildren. For someone over 50, choosing to lead a life that is not conventional or normal enough can have an impact on their emotional and mental wellbeing. It, therefore, comes as no surprise that only a few of the 10.38 crore senior citizens (people aged 60 and above) in our country chose to tie the knot in their sunset years.

But there is a change, even though subtle and slow, in our elderly population, most of whom are baby boomers, born at the end of World War II. “The baby boomers have a curiosity about life,” says Dr Shruti Madgavkar, a psychologist with P.D. Hinduja hospital in Mumbai. “They want a chance to stave off decay, have fun and enjoy. In the age of technology, with many older people taking well to WhatsApp, they are more aware and assertive of their choices.” She says she has seen a significant change in the mindset of the elderly of today as compared with those about a decade or two ago. “We now have men in their late 70s and early 80s, too, who dye their hair, women who wear jeans and much more,” she explains. “The assurance of having a partner in one’s later years contributes to mental and emotional stability. But it will be a long time before it gets accepted fully in our society.” A number of dating sites, including Truly Madly, are encouraging “seniors” to register and “look actively for partners”. “We are seeing a steady number of hits when it comes to seniors looking for companionship,” says an executive from a popular dating website.

A study in rural south India, published in 2015, found that about 27 per cent of the older population (60 and above) was sexually active. It progressively dropped with age, and none was sexually active after 75. With sex seen as a mere procreative tool, the elderly are expected to suppress their desires and live a sedate, solitary life. Many older adults, therefore, seldom express their desires, sexual or otherwise. “While companionship goes beyond intimacy, the latter, too, is an important factor in establishing mental peace,” says Madgavkar. “We need to rid ourselves of the notion that our seniors cannot live a fulfilling life as the young do.”

But what drives senior citizens to seek company and comfort the most is the dull ache of loneliness. In his research paper titled 'Companionship and Sexual Issues in the Ageing Population’ in the Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, Abhishek Ramesh from the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru, writes that the pandemic brought this subject into sharp focus, with partners separated because of lockdown, isolation, or loss of partner, which eventually led to loneliness, isolation, and grief.

Agrees Dr Sujay Joshi of Dignity Foundation, which works towards mitigating loneliness in the elderly. “Not that it was absent earlier, but it has become more pronounced now,” he says. “What we need in India are low-cost social spaces where the elderly can meet, and spend quality time together. That is because companionship has no substitute.” Dignity Foundation has 25 companionship centres, also called Chai Masti Centres, across India where those over 60 come together to spend quality time for at least two hours a day, five days a week.

According to Aparna Shankar from the department of psychological sciences, Flame University, Pune, “loneliness is common as people age and it has a significant impact on health and wellbeing among older adults”. She also quotes from the Wave 1 of the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) that came out in 2020, which is the only such comprehensive survey of the elderly in India brought out by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare along with the International Institute for Population Sciences. According to the report, in the surveyed years of 2017-18, more than 25 per cent of the population belonged to the 45 to 80 and above group; of this, close to 14 per cent fell in the 60 and above age group. In the 60 plus group, the married constituted 61.6 per cent; of this, 36.2 per cent were widowed. Only 43.9 per cent in this age group reported to be satisfied with their lives. And, as per the report, the elderly population in India is expected to rise from 8.6 per cent (2011 census) to 19.5 per cent by 2050 and those over 45 will constitute 40 per cent of the population by the said year. The report also stated that 20.5 per cent of adults aged 45 and above reported moderate loneliness, while 13.3 per cent reported severe loneliness. “Loneliness has been identified as a determinant of cognitive decline and dementia as well as of poor physical functioning and disability among older adults,” says Shankar. “Similarly, loneliness is associated with an increased risk of developing depression with evidence suggesting that this association may also be bidirectional. Poor health, poor functional status, worse mental health and cognitive problems are important determinants of loneliness among older adults.” The prevalence of diagnosed psychiatric problems among the elderly, says the LASI report, is 2.6 per cent and that of depression is 0.8 per cent. Those who are separated, divorced, deserted and living with others (relatives) are more likely to be depressed, says the report.

This brings to the fore the need for company and companionship in one's later years, especially as families go nuclear. And while there are companies like Goodfellows, backed by Ratan Tata, that employ young graduates to provide company to senior citizens, Dr Sridhar Vaitheswaran of SCARF says, “The main support comes in the form of remarriages in one's later years, with a belief that there is someone to talk to at any time of the day and someone to share the rest of one's life with.” With age, the contours of love and relationships evolve and are modified as needs and priorities change. “Remarriage is done out of choice,” says Vaitheswaran. “It is about companionship and being loved, which is very important. When you are older and wiser, you make smarter decisions when it comes to choosing a spouse because you have more experience and it is not your hormones that do the talking. The decisions are refined because the choice is not driven biologically.” As far as society’s views on remarriages among the elderly are concerned, they are simply outdated misconceptions about ageing, he says, adding that not many people lived for this long in the earlier days.

Abdullah Mangarun from the Mindanao state university in the Philippines recently published a research paper in which he examined the lives of older couples after remarriage via their “experiences, including doubts, fears, apprehensions and satisfaction of their decision to remarry”. The important themes that emerged from the study were that remarriage brings forth newfound happiness, contentment, lifelong companionship and graceful ageing. “Therefore, successful marriage in old age is possible when both are ready to take on new responsibilities,” says Mangarun. “There is fulfilment for a better quality of life in old age when both know how to give and take in a relationship.”

A few years ago, Nathubhai Patel, 73, from Vasna in Gujarat, founded Anubandh Foundation that holds weddings for senior citizens in India. Till date, he has helped 195 couples aged over 52 years get remarried. “Our children have no time to devote to their parents,” he says. “Both sons and daughters are equally busy and it gets difficult for the aged to spend time every single day all by themselves.” The foundation gets more than 10,000 biodata and has community sammelans across cities, attended by some 50 women and 150 men from diverse communities. But not all relationship made here succeed. “At least five to six of the weddings that we have organised so far have failed,” says Patel. The reasons are many: conflict between the woman and her in-laws, lack of support from children over property disputes and the incessant demand for sex by men over 70. “Women mostly want a partner who is well-to-do because they do not want to go through the struggle again, and men prefer women without strings, that is without children, because they want their second innings to be responsibility-free,” says Patel. “But primarily, those marriages work where the emotional interdependence and good mental health of both is of crucial importance to each.”

THE WEEK talks to a few such couples to understand how they negotiate societal stereotypes to live life together on their own terms.

EQUALITY WITH HONESTY

Actor Suhasini Mulay, 72, was no believer in the institution of marriage till she met Atul Gurtu, 76. She was 60, and he 64 when they met. “I always thought that there were more unhappy marriages than happy ones,” she says, “because it is always an unequal partnership in which the woman bears the brunt of homely duties and child-rearing responsibilities and the man holds responsibility of neither.” With no intention of getting married ever and also because she had given up on the hope that her ideal man would come her way, Mulay from Mumbai found Gurtu on Facebook by a stroke of serendipity. She had created her profile on the social media platform, on the insistence of a younger colleague, to bag more work. While causally surfing one day, she came across the profile of a particle physicist at CERN in Geneva who was decoding the working of the universe. The experiment was of interest to Mulay and she sent him an email asking about it. A few exchanges later, he asked for her mobile number, to which Mulay, aware that he was looking for companionship, simply wrote, “Good girls don't give mobile numbers to strangers.” There was silence at his end.

TRAVEL PARTNERS: Suhasini Mulay with husband Atul Gurtu

TRAVEL PARTNERS: Suhasini Mulay with husband Atul Gurtu

Mulay did her own background check and found him to be genuine. Gurtu had lost his wife, Pramila, to cancer and his son, too, had died earlier. “There was a need for companionship that was above anything else,” says Mulay. “He was emotionally very vulnerable as Pramila had expired barely five years before we met.” Gurtu was keen on meeting her but she wasn't sure. He then wrote something that changed her mind: “You seem to be very happy and busy with your life and I wish you luck. But remember if you want any change in your life at all, it will not happen automatically.” Mulay rang up a friend of hers who had remarried, at around the same age as her. He told her that her friend circle would diminish with age and that there was no harm in taking a chance because it was important to have a partner for one's mental and emotional wellbeing at a vulnerable age. What finally convinced her was an article Gurtu wrote in a magazine on what happened when his wife was diagnosed with cancer. “He said how he wanted to make her live out all her wishes for as long as she was alive,” recalls Mulay, “and I think that quality of putting the other before self is what struck a chord with me.”

On the night after their first date, Mulay wrote down things she would not compromise on and one of them was equality. She was fine with him being a vegetarian and a teetotaller as long as he had no objection to her partaking in these things. To him, the only non-negotiable factor was honesty. He told her that even if she ever decided to cheat on him he would rather hear it from her than from someone else.

As they met in restaurants, they realised that they had similar views on many issues. Around that time, he was to retire in a few months and wanted help rearranging the furniture. She readily agreed to see him at his place. Something as simple as him writing down the measurements as she took charge with measuring, she felt, had broken stereotypes. “It became very clear very soon to me that I wanted to spend the rest of my years together,” she says. Gurtu was a bit unsure initially about whether they would click; he wanted to give it a try nonetheless. If things did not work out, they would “simply shake hands, kiss and part”. “We are nearing the end of our lives and I want to walk with you for as long as I can walk with you,” he told Mulay. Members from Pramila's family, including her eldest sister, embraced and “adopted” Mulay, and Mulay's mother and sister welcomed Gurtu, after being “super impressed by him”. “She [mother] asked why he wanted to marry at this age and he said I know Suhasini can live her life on her own, but if you are given a chance, then it is stupid not to try.”

That clarity comes with age. Mulay, in fact, got “quite worried” in the first year of their marriage because they never had a fight. But they realised that their fights were no longer about their respective egos. “By now we know better than to feed our egos,” says Mulay. “We simply sit down, talk and discuss and make it a point to listen to each other. I don't think we'd have had this sort of patience earlier.” For instance, Gurtu disliked Mulay using her phone while dining, and just asked her, “Can this wait 15 minutes?” From that day on, Mulay ignores her phone at the dining table.

Eleven years on, the couple has found their rhythm to negotiating everyday life―he prepares the morning tea, does the laundry; she cooks one meal at home everyday; and the two prepare a five-day meal plan in advance. “Atul does not know how to cook and we don't have a full-time maid,” says Mulay. “So if I am home late from work, he doesn't wait for me to fix something, [ordering food from outside and making] sure there is food on the table. I think that also takes maturity of another kind. He is not a man-child; he is a grown, mature man.” On her shoot days, he takes charge and on her off days, they work together.

One thing that has stood out for a self-employed person like Mulay is the financial support and stability he brings with his fixed monthly pension. “Also, when we got married, I was very jittery about his money and my money,” says Mulay. “But now I have realised that marriage is also financial partnership.”

The couple does not believe in a happily-ever-after; they know that marriage is actually a lot of work. “We both know that at our age people do not expect us to have romantic relationships, but it was only important for us that our families embraced our partners,” says Mulay. “With each other, our emotional needs are met and that's what matters.”

COMPANY, CARE

It is 7pm on a weekday when Vijay Shenava finally finds some time to reply to a phone call he had received earlier in the day. At 69, he follows a set pattern of living that keeps him occupied through the day, leaving no time for chit-chatting with friends. Perhaps, a separate slot must be reserved for that or an appointment will be great, he quips. “At my age, it is a privilege to have something to do every day and not have to suffer the misery of idleness,” he tells THE WEEK from his Mangaluru residence. “Even more significant is the reassurance that one doesn't have to go through one's remaining life all alone. It gives me immense mental peace and emotional sanity in knowing that there is someone with me in this house.”

That ‘someone’ is Shobha, 54, his second wife, whose presence, he says, brought him back from the black hole of “unending anxiety and depression”. Ever since Sarala, his first wife and mother to their two children, died from kidney failure in 2013, Shenava felt as if a part of him had been taken away. The couple had been together in a “happy and healthy marriage”, with her working as a manager with a public sector bank, while he attended to their children and looked after their agricultural land. He would cook, clean and care for the kids while she would be at work. He would make her a warm cup of tea on her return after a long and tiring day. Shenava, a man of few words, found it challenging to deal with her loss. With her gone and the children married, the house felt “hauntingly empty and lonely”. “I realised how lonely I was when it was the end of the day and I had a bunch of things to talk about but nobody to talk to,” he says.

While his daughter Karishma, a makeup artist, moved to Mumbai after marriage, his son went abroad. Shenava, ailing and alone, became “extremely anxious and at the same time his forgetfulness increased”. “He would often call me multiple times in a day just to make conversation,” says Karishma. “And despite hiring several house helps, none would stay because his frustration, frequent bouts of anger and paranoia would drive them out.”. While his children would visit him often, he soon realised that he needed someone who could love and trust him and he could do the same in return. “Most important, someone who could take care of me because I am not in good shape and I have nobody to look after me on a daily basis,” he says.

That's when a friend suggested second marriage. Shobha, said the friend, was from the same community, a widow without kids. It was too daunting to consider, he says, but he also knew he was too vulnerable and helpless. “I have three grandchildren and I wasn't sure how my kids would take it,” he says. Karishma accepted his decision.

While Shenava was seeking company, Shobha was struggling with a “deep sense of loneliness” post her husband's death. “She came with no expectations, except that her future will be secured after my father,” says Karishma. “She is warm and friendly, keeps herself busy with household chores and looks after my father. In terms of chemistry, both are chalk and cheese. They do not speak much, and neither are overly expressive to each other, but it is their presence that matters to them, more than anything else.”

Agrees Shenava, “She and I are two very different people. But now there is nothing we can do about it. We have to be together come what may and that's what matters. She is my support system. I cannot live alone anymore. It is frustrating and I can go mad.” But he has no unrealistic expectations. “We are not head over heels in love with each other, but we sure are there for each other whenever the need arises,” he says. “Just the fact that she's around has helped. Now, there's a spring in my step and I feel so much better.”

SENSE AND SENSIBILITIES

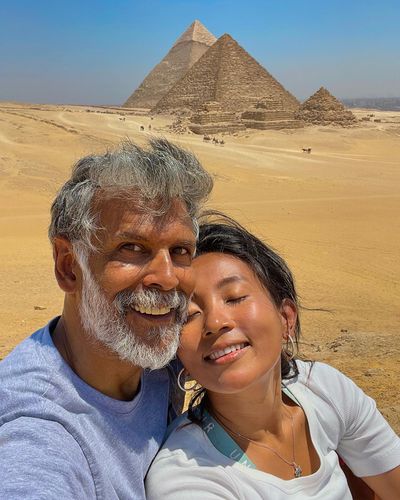

A lot got written about when model-actor Milind Soman, then 52, married Ankita Konwar, an air hostess half his age. It was his second marriage and hers first. Despite the age gap, they connected at an emotional level and “that is all that mattered”. For him, Konwar was the stability he longed for and, for her, he was that raging ball of energy and enthusiasm that her calm and collected self needed.

“It turned out we complemented each other just right,” Konwar tells THE WEEK at a suburban restaurant in Mumbai. Dressed in a casual top and denims, she is a frequent patron and warmly greets the staff as she calls for two cups of chamomile tea. “We connected on a temperamental level, at a time when I was emotionally vulnerable, having lost my boyfriend barely a few years before meeting Milind; it simply extended to a deeper subconscious level because the two of us were so much alike.” To an extent, that surprised her, too―that a man double her age could meet her at so many levels. He eats early dinner; he prefers staying indoors over attending late night parties; he is deeply enthused about the environment and loves to keep himself fit―all of this mirrored Konwar’s sensibilities. “He is more active on social media,” says Konwar. “He is also more jumpy when it comes to trying out new stuff, including high-on-adrenaline activities. But thankfully, both of us have a very small inner circle of people we call friends. We don't show off. We don't flaunt. We do not live the celebrity life. We eat home-cooked food every single day. And neither of us was ready for kids. That's what this marriage is about.”

But did she ever feel insecure? “I hold myself in very high esteem,” she says assertively. “Nobody can dent my confidence. But if you break my trust, I will let you go.” That Soman’s parents and grandparents on both sides were very well educated, rooted and yet had a liberal thought process was also a factor that clinched the deal for Ankita.

A day in their life begins with an early morning run together, followed by yoga and tea together before moving to their respective work commitments. Konwar is turning her passion into work―she has just started her first foray into running by holding the Invincible Women marathon in Mumbai. And the face of the event is none other than her husband. “I want to be known as a fitness entrepreneur because that is what both me and Milind are conscious about,” she says.

Age, she asserts, is really just a number. “Who better to tell you that than me,” she says. “My husband is a living proof of it.”

MAKING PEACE

“I never really thought there would ever come a time when we would be forced to address someone else as mother,” says Amrapali Chavan, as she talks about her father Atmaram Shinde’s second marriage to Sulochana, a year after their mother died in 2010. For Amrapali, 34, and her sister, Mrunali, 25, it was an “emotionally draining moment” to see their father tying the knot with a woman who was 15 years younger to him, and came with two daughters who were almost the same age as them. All Shinde knew was that he “felt the need for company and the urge to move on with life”. “When love knows no age, why do we gawk at couples who come together for love, so as to be able to walk into the shadows with a partner?” he asks.

Shinde, 65, and Sulochana, 50, have a son together, five-year-old Arsh. Both have grandchildren, too, from their respective daughters. Arsh is only a year older to Amrapali's son. “My son and my brother are almost the same age. This is just so crazy,” she says, animatedly.

The emotional toll on grownup children, resulting from a marriage between parents who have long crossed their prime, can be long-lasting and deep. “I remember seeing him breaking down very often in front of our mother's picture long after she was gone,” says Amrapali. “He was emotionally distressed and had receded into a shell. But I would always assure him that things would be fine and that he could count on us for anything and everything. But his friends and those in the neighbourhood didn't let him be. The society put so much pressure to remarry, that he just gave in. They kind of brainwashed him into thinking that he would die all alone with nobody to care for him.”

Around the same time, Sulochana lost her husband to a snakebite. Sulochana, too, was anxious about being single again, given that “society looks at such women in a different way”. She met Atamaram through a friend in their hometown of Alibaug, a few kilometres off Mumbai.

Amrapali was about 20 when her mother died and her sister just 10. “My mother's death in a way also brought all three of us close to each other and we assured papa that we will take good care of him,” she says. “But what mattered most to him was companionship and the love of a spouse. So, while he did get someone who takes care of him now, we feel as if our share of love has now gone to someone else.”

Shinde disagrees, saying it was not easy for him to marry again. “I was on the verge of an emotional breakdown,” he says. “But I took the plunge. I cannot live in my daughters' house. Right now, my wife and I have realised that there is a huge age gap between us and that is why we have issues understanding each other. Many times, we thought of quitting it altogether but the birth of our son has added a new meaning in our lives. I am not financially capable of raising a family all over again but I am fully able to provide with emotional support because I am in a happy place myself, no longer temperamental, irritable and fussy.”

As of now, Shinde's family's expenses are being met by his daughters. “It is difficult to refer to her as 'mom' because we are in the same age range,” says Amarapalli. “Just that she takes care of my father and has found a purpose in life in the form of a son is good enough.”

BITTEN BY THE LOVE BUG

In May 2022, retired cricketer and commentator Arun Lal, 68, made news for marrying his long-time girlfriend Bulbul Saha, 39, who was his friend's daughter-in-law. “I am quite literally god's child. I am very lucky in both love and health,” says Lal, a cancer survivor and a divorcee and a father of a son in his 30s. Saha says they share great chemistry “because he likes to father me, and I get to mother him”. “The age gap never becomes an issue because love triumphs all else and we both make each other happy in the mind,” she says. “I know I will never be mentally stressed or emotionally depressed in his company and that to me is very important.”

Arun Lal and his wife Bulbul Saha | Salil Bera

Arun Lal and his wife Bulbul Saha | Salil Bera

There have been times she says when she has changed her entire attire before leaving for a party only because he wanted it. “You know with age a person kind of becomes rigid and that does lead to conflicts between us at times, but then that's okay,” says Saha, a school teacher.

Saha and Lal met on a trip at a time when Saha was out of a relationship and the two of them hit it off instantly. Saha was under pressure to get married and Lal had to take the step, knowing fully well that not many would understand his intentions behind seeking a divorce and a remarriage, that too with a young woman who is his daughter's age. “I have done no harm to nobody,” says Lal. “Love knows no age, it is just that the society is so severely biased towards us silver splicers. It was mentally debilitating to gather the courage to go out in public because we did not want to hurt anyone. For a long time, our relationship was very discreet and my need for companionship was immense, especially since my wife had not been keeping well for years due to multiple strokes.”

Lal lives with both Saha and his first wife in a duplex bungalow in suburban Kolkata. “We take care of her together,” says Lal. “She has got nobody else in her life, except me. In fact, Bulbul (Saha) also shops for her, looks after her and, God forbid, if something were to happen to me then the only source of security for my ex-wife will be my current wife. I also believe that if I were to have a stroke tomorrow and were unable to move, then my present wife will take care of me and my wife like my daughter.”

Once their marriage became public, there were nasty comments, anger, disillusionment and breaking of ties but Lal has been an “eternal optimist”. “It is a beautiful feeling to be loved and to feel wanted in one's sunset years,” he says. “Because it is the loneliness that creeps in like a bug, not letting you be. Despite all the pressures, tensions and criticisms, we are steadfast in our loyalty towards each other and we will make this work.” The two are planning to have a child soon.

LOOKING FOR LOVE

Smita Vinchurkar, 48, flaunts a pixie haircut, a septum piercing and dons ‘cool’ outfits. “But these aspects are working against me when it comes to finding a partner for myself,” she says, over a cup of coffee at her home in Mumbai's suburban Prabhadevi. “I am not taken seriously and somehow my so-called type doesn't fit into this stereotypical image people have of a woman in her later ages.”

Seeking company: Smita Vinchurkar | Amey Mansabdar

Seeking company: Smita Vinchurkar | Amey Mansabdar

It is evening on a weekday and she is preparing to leave for her night shift (7.30pm to 4.30am) at a BPO where she has been working past year. Vinchurkar went through a “bad marriage” in 2004 while she was still in her early 30s and it took almost a decade for the divorce to go through. She used to live with her mother till her death a few years ago. And that is when she had to come face-to-face with loneliness. “It is my desperate desire for companionship and intimacy. But it is frustrating to even contemplate a serious relationship at this age,” she says, having tried her hand at various dating sites in vain. “In the Indian context there is only this one age bracket when women can think of relationships. After that, it is too hard for people to digest that even those nearing their 50s have the right to start a love life afresh. Men do not think of me as a girlfriend or a wife material; they think I'm easy. I was asked multiple times if I know how to cook and clean, if I know how to manage the house.”

That began affecting Vinchurkar's mental health, and she receded into a shell, seldom stepping out of the house. “I literally began questioning myself and asking if there was something wrong with me,” she says. “And then gradually I began to simply ignore the naysayers, the critics, those who shamed me for being single and ready to mingle at this age. I have begun doing positive healing courses and have claimed my life for what it is.”

Bold and enterprising by nature, Vinchurkar dabbles in multiple things―travelling, photography, soap making and her latest love―pottery. “It gives me immense peace to really learn new things and learn more about myself,” she says.

Vinchurkar feels she has been particularly “unlucky” in terms of romantic relationships so far, but is not ready to give up. “I will continue to actively look for a companion because the very thought of loneliness in my old age scares me to bits,” she says. “Although I have a very loving sister and her family that's very dear to me, there is an age gap of eight years. I do not want to die alone. I want someone to love me before I die. I hope society stops making it difficult for people over 40 to enter into romantic relationships that last a lifetime. We, too, can have it all.”