Most people open the front door in the morning and see light that often powers their day. But for days together Devananda saw only darkness. It seeped inside her home, and engulfed her family.

The dark days had started last October when her father Pratheesh P.G., 48, was diagnosed with liver cancer. None in their family had heard of decompensated chronic liver disease with hepatocellular carcinoma—the medical name for his condition—nor about non-alcoholic fatty liver which the small businessman was diagnosed with along with the cancer.

Life crashed. Devananda found her father fatigued most hours. Sometimes semi-conscious. And when awake, he struggled to talk. Devananda, 17, froze at fate's harsh twist. But she did not submit.

Still she didn't have a clue what to do in those early numbing days.

As the family struggled to absorb the shocking news, they were advised that an immediate liver transplant was the only option.

Stressed from the shock of seeing the family's breadwinner struggling for life, and stretched thin on the financial front, Devananda and mother Dhanya ran from pillar to post. It seemed time was steadily running out for Pratheesh, and no donor seemed in sight.

“Finding a suitable donor and arranging money for the transplant seemed an impossible task, as one by one the doors closed on us,” said Dhanya.

Pratheesh runs an internet cafe and printing shop in Thrissur, his hometown, about 90km north of Kochi. The shop is on lease, and the only way to arrange the money for surgery was by pledging their house. “He was vehemently against the idea. He used to ask us how we would repay the loan in case something happened to him,” remembered Dhanya.

Finding donors was another battle. When Pratheesh was diagnosed with liver disease, the family was told he perhaps had six months left. “It was very hard to find a donor. A member of our family came forward, but later backed out,” said the daughter.

The last few months of the year were painful. Quite like what they had experienced in October, when Pratheesh and his family came in for consultation at Kochi's Rajagiri Hospital with swelling in both legs, onset of jaundice and fatigue. His illness worsened, with sepsis and encephalopathy, a condition that affects the brain. Further tests revealed that his Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) Score, from tests to assess liver damage, was high, and that he had cancer.

“Added to liver disease, scans revealed he had a tumour,” said Dr Ramachandran Narayanamenon, the transplant surgeon who treated Pratheesh. “CT and PET scans were conducted. At first, since there was a tumour, the transplant option did not seem viable. Further evaluation of the patient had to be done.”

Pratheesh’s liver condition being poor, doctors had to rule out many treatment options like transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation and stereotactic body radiation therapy to stabilise tumour growth . Since the chances of liver failure were high, bridge therapy (to suppress the tumour) till transplant was also ruled out.

Pratheesh’s blood group was B-ve and not compatible with Dhanya's. The two children, Devananda and Adinath, being minors studying in class 12 and 7, respectively, could not become donors. The next option was to join a long queue, and wait for a match. Because of the tumour, the chances of getting a donor were low. “The cadaver criteria laid down by the state make it difficult to consider a deceased donor for transplant,” said Narayanamenon. “Therefore, immediate family members or relatives are usually relied on as donors, and since there was none in this case, the family was placed in a dire situation.”

“Amid financial woes and difficulties in finding a donor, and with my father’s condition worsening by the day, we knew that we had only limited time to do something to save him. We couldn’t afford to lose him,” said Devananda.

As most doors closed on them and with hope at its lowest, Devananda wondered aloud one day, “I could be the donor, can't I?” Since her blood group was O+ve, she was in the universal donor category. However, one of the major challenges ahead was the law.

“I voluntarily came up with the desire to donate my liver,” she said. “I knew that I am a universal donor and, if everything goes well, I could save him. It was certainly not an easy decision. When you love someone so much and something happens to him, you would go to any extent to save his life. At that moment I had only one desire—to get my father back at any cost.”

Core strength: Pratheesh with wife Dhanya (to his left) and children Devananda and Adinath | Rahul J. Mohan

Core strength: Pratheesh with wife Dhanya (to his left) and children Devananda and Adinath | Rahul J. Mohan

It was not easy for Devananda to convince her father. “Why sacrifice for me,” he asked, “when you have a whole life ahead of you?”

“I first posed the idea to my mother. Initially, she didn’t even consider it. I was not sure if it was even possible, but that was the only way to save him,” said Devananda, then a student of Sacred Heart Convent School, Thrissur.

There were many who tried to change her mind, warning her of all that could go wrong, but she stood firm. “Once it was clear that this was a possibility, my family stood by my decision,” said Devananda. “Many cautioned me. They told me that it would be extremely painful. But it never occurred to me as something painful. After the surgery, they asked if I regretted the decision. I will never regret it. When it comes to loved ones and family, I don’t consider physical pain to be a pain.”

Even when there was no hope, it was Devananda’s unwavering will that paved the way for the long battle that lay ahead. “We could see this family was different,” said Narayanamenon. “They had a special sort of courage and willpower. Even we had nearly given up hope, with his condition worsening. Devananda was very brave. When her mother came to me with her minor daughter willing to donate a part of her liver, we did not even want to consider it. We explained to them the medical and legal complications. After all, she is just a child. Yet they were persistent.”

And soon they took their battle to court.

The legal battle was tough. The Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994, does not permit organ donation by a minor. On December 20, Devananda went to the Kerala High Court seeking permission to donate a part of her liver.

The court passed an interim order directing the 'appropriate authority' to hear the case and arrive at a decision. An expert committee, comprising three specialist doctors, was appointed by the authority to conduct a detailed evaluation of the case after examining the medical reports of the patient and the opinion of the doctor. The committee concluded that Pratheesh “is beyond the liver transplant criteria for hepatocellular cancer in the background of cirrhosis of the liver”.

And once the committee said that Pratheesh was not a candidate for liver transplant, Devenanda’s request was declined, too.

“Time was running out,” said Devananda's counsel, advocate P.R. Shaji. “If we were not able to convince the court how serious the issue was, the attempt would prove futile and we wouldn't be able to save his life.”

Devananda was shattered. Said her mother: “My daughter and I visited the members of the committee and explained to them our situation. We wanted a solution from them. If transplant was not an option, what was?

“They were unable to show a way ahead. It felt as if they were not giving us a chance. We couldn’t just sit idle and wait for him to die. We had come a long way after making up our minds for this, and therefore we went ahead with an appeal.”

Dr Ramachandran Narayanamenon | Vishnudas K.S.

Dr Ramachandran Narayanamenon | Vishnudas K.S.

Shaji argued in court that the 'appropriate authority' had focused entirely on Pratheesh’s health condition, rather than Devananda's capacity to donate. “As long as the donor is medically fit, is a near relative and a voluntary donor, the 'appropriate authority' is bound to grant permission,” he argued.

Though the act prohibits minors from donating, there are certain exemptions, and it was finally up to the authority to take the call. “I had to change my line of argument,” explained Shaji. “I spoke with various expert doctors in the field and familiarised myself with the technical and medical issues involved in an organ transplant in such a situation. I also studied the existing protocol for liver transplants.”

In the meantime, experts from Rajagiri Hospital informed the authority that only a liver transplant could save Pratheesh’s life. “The chance of recurrence of the tumour cannot be ruled out, but it is not a deterrent for a transplant,” said Narayanamenon. “In certain cases, when the tumour spreads outside the liver, a transplant is ruled out. In Pratheesh’s case, it was not so.”

A tumour in the liver would double in just three months, which is much faster compared to tumours in other organs. So a delay in surgery could lead to severe complications such as vascular invasion, a complication when the tumour invades major blood vessels.

Another sign of such complication is the rise in tumour markers, the proteins produced by the tumour, in blood. In the case of liver cancer, the marker is called AFP (alpha-fetoprotein). Radiation and related treatment to reduce the tumour size, known as downstaging technique, is then performed.

Through downstaging therapy, the tumour is reduced to make it feasible for liver transplant. The patient would be placed under observation and, if the tumour is not spreading, the transplant is done.

In Pratheesh’s case such an option was not viable as his liver was at risk and he wouldn't be able to withstand the downstaging therapy. So it had to be an immediate transplant. The complications in Pratheesh’s case were detailed and reports submitted to the authority by the doctors treating him. The authority and committee reevaluated the situation. “They studied the existing protocol of liver transplantation, which made the committee reevaluate the reports by the hospital and allow the petitioner’s plea,” said Shaji.

Devananda’s tests and all procedures before finalising the donor were yet to be done. After the court granted permission in December, Devananda was prepped for tests. When her test results revealed fatty liver, doctors were taken aback. “Fatty liver was not a good sign at such a young age. We were back to square one,” said Narayanamenon.

Devananda had almost won the battle. Now, to think that she was the reason doctors were unable to proceed, it hurt her. “All the struggles seemed to be in vain,” she said. “It was my mother who stood by me in those difficult times. The doctor also said that we could give it a month’s time and see if the condition gets better.”

With a disciplined routine and strict diet, Devananda started tackling the fatty liver. Restrictions were put on food. “I used to love rice but I had to reduce its intake,” she said. “I used to wake up at 5am and go to the gym by 5.30. I would be back by around 7.30 from the gym. My mother used to drop me and pick me up. Then I would go to school and be back by 5pm. Then followed schoolwork. The diet was assigned by the doctor and we followed it.”

The doughty fighter stunned the doctors. Her CT scan was clear this time.

Pratheesh had to undergo tests yet again to check the status of the tumour ahead of surgery. If the tumour had spread, they wouldn't be able to proceed. “Normally in liver disease cases, a majority of patients would have issues of alcoholism and improper lifestyle. In Pratheesh’s case it was a surprise as he had never taken alcohol,” said Narayanamenon.

The surgery was fixed for February 8. “There is a misconception that transplant is the last option,” said Narayanamenon. “It is not the last, but the best option, provided you do it at the right time. When you reach end-stage liver disease, there is not much time left and we need to perform the surgery quickly. The stabilisation process (which can take up to two weeks or more) is conducted then. In certain cases, the whole process could be fatal.”

Dr S. Sudhindran, chief transplant surgeon at Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, thinks that women are more altruistic in nature than men. This would explain why, even as the law forbids it, young girls are willing to be organ donors, despite the risk of major complications. While Devananda won the legal battle, it should not send a message that this is normal, said Sudhindran. “It is not a simple thing at all. There is no doubt that she is very brave,” he said. “People think that it is a minor procedure, and that the surgeon will take just a small part of the liver that will grow back. A liver transplant is much more complicated than, say, a kidney transplant.”

Bile leak is a major post-surgery compli-cation. It leads to infections and the patient can take months to recover. Occasionally, the need to insert a tube and carry out endoscopy may also arise.

Working a miracle: The team at Rajagiri Hospital that was involved in the transplant surgery.

Working a miracle: The team at Rajagiri Hospital that was involved in the transplant surgery.

“Devananda is a determined person,” said Narayanamenon. “When we told her about the difficulties involved, she sought ways to overcome them.” When Pratheesh was asked whether he was in a state to proceed with the surgery, he said, “If I recover, I will be able to look after her and the whole family.”

Everyone knew that it was now about two lives. It got scary and risky. “Even a slight allergic reaction to the medicine would compromise her. We went by all protocols and explained the process of the surgery,” said Narayanamenon.

Since there was a possibility of blood clots during the transplant, the organ could turn dysfunctional. “For any general surgery, medical risks involve multiple organs—say, a heart attack, stroke or pneumonia,” said Narayanamenon. “And surgical risk involves bleeding and graft dysfunction. Due to various factors, grafts may go wrong. Post transplant infection and major blocks in blood vessels are some of the risks. They may not manifest on the surgery table, but occur on subsequent days.”

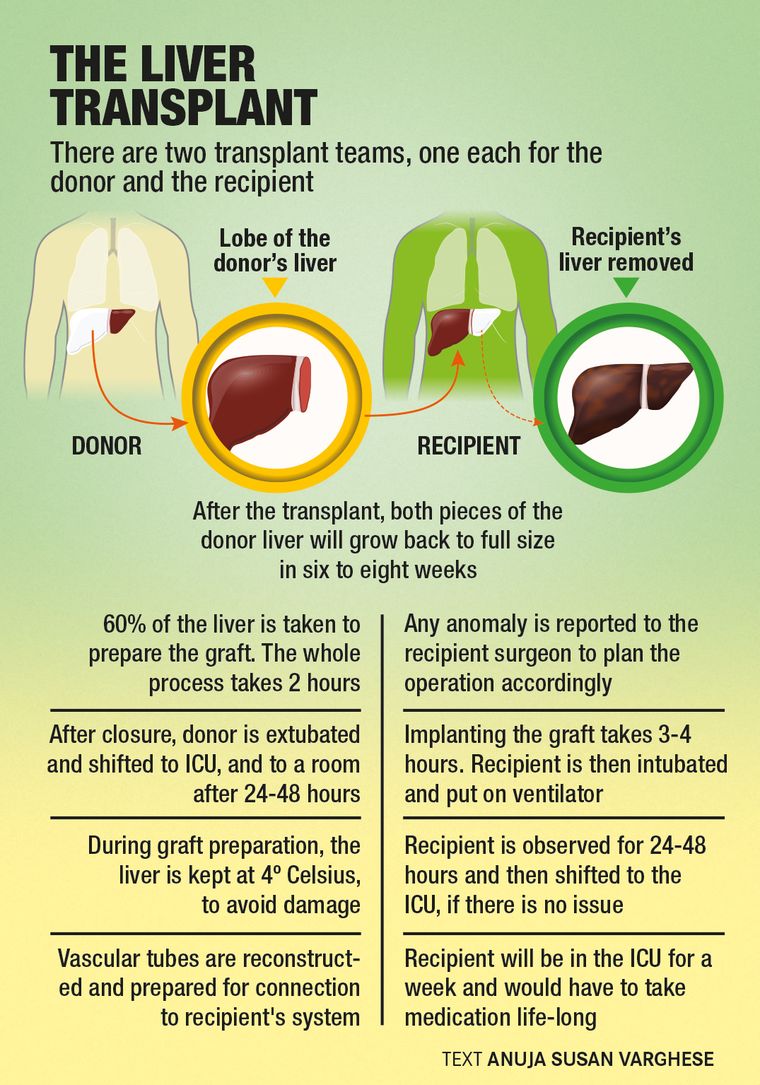

But by now everyone in the family knew the brighter side. The major advantage of the liver is that whatever portion of it is taken, it grows back. The liver regenerates after the initial complications are overcome. “We normally take the right portion of the liver—the right lobe,” said Narayanamenon. “For the transplant, roughly 60-65 percent of the liver is to be taken. The left lobe has only about 40 per cent and that is enough for it to grow back. But if any major issue occurs, then it won’t work and the donor will be in liver failure (which can happen in one in 350-400 donations).”

With young donors, one of the advantages is that they recover within a month. They can go back to their routine sooner than expected. Physical exercises are encouraged, including cycling and badminton. Physical activities are good for the liver as well.

When Devananda was being prepared for surgery, doctors had asked whether she would prefer to be given anaesthesia from her room—that way she would be in sedation while being wheeled in to the operation theatre. Her mother recalled her saying that she wanted to see the operation theatre. “Till now we have seen it only in the movies,” joked Devananda.

“She thinks she can calm everyone by saying such things but I knew how scared she was deep down,” said Dhanya.

Both the recipient and donor were brought at the same time to the operation theatre. The surgery took place in two theatres. There are two teams: donor and recipient. The team had five surgeons and the anaesthetist. The initial one and a half hours are usually taken for putting lines on the patient and giving anaesthesia. The donor surgery is done first, after which the patient is transferred to the ICU. Two days later, depending on the recovery, the donor is shifted to the room.

For the recipient, it is a complicated surgery. The major risks during the surgery involve bleeding, blood pressure and heart rate issues. Major bleeding could affect multiple organs. A lot of “bench work” is required while the doctors place the liver from the donor. Reconstruction of the portion from where the liver is taken is known as benching; it takes about an hour and a half.

The time in the theatre will soon turn into a haze for Pratheesh. “My daughter was bolder than me,” he said. “Even when the doctors explained the risks involved, she gave me the confidence to go ahead with it. The success rate the doctors had told me was 65 per cent due to various issues.

“Even the day before the surgery was tense. They had detected a variation in the PET scan and if the results were positive then they had to drop the surgery. Thankfully, it was negative. Had it been positive then I would have been alive only for six months.”

When Pratheesh opened his eyes after surgery, by around 9pm, he inquired about his daughter. The words “she is fine” from the doctor made him overjoyed.

On February 23, Pratheesh came home. And two months later, he is almost back to normal life. “The struggles and pain during the initial days have gone now,” he said.

Both Pratheesh and Devananda have been placed on a strict diet, staying off fries and oily food. Breakfast comprises protein-rich food, including the whites of six eggs. Since Devananda was diagnosed with fatty liver, doctors have advised her to monitor her food intake. Dosa, chapatti, peas, fish and chicken are part of the diet, while fried chicken, fried fish and beef are off the table. “Rice, being rich in carbohydrates, can only be taken in small portions,” said Dhanya.

Rajagiri Hospital had waived off Devananda’s medical expenses, including the donor surgery fee. After being discharged, Pratheesh was not expecting so many followup visits to the hospital. Till May, he has had to revisit more than ten times for checkups. These visits, which are scheduled by the doctor after assessment, and unplanned hospital admissions in case an anomaly is detected, have taken a toll on the family's finances. The surgery cost around 145 lakh, with around 15 lakh needed for followups and medicines. A loan and the small income from the shop have sustained them. “If things get worse, we don’t know how we will be able to handle it financially,” said Dhanya.

But Devananda is looking ahead. “I always wanted to pursue the medical field. I want to become a doctor and will prepare for NEET and try for a high rank,” she said.

Days spent at the hospital recuperating after surgery, where she witnessed for herself the power of healing and how doctors touch lives, seem to have strengthened her resolve.