Do not send your son to school tomorrow. If you do, he will return soaked in blood or dead.

This chilling statement was made by an eighth grader. He had called up his classmate’s mother to warn her of dire consequences. Just half an hour before the call, he had pushed the classmate in front of a moving truck while on their way back from evening tuition. Luckily, a passerby pulled the classmate away in time and saved his life. Though uninjured, it left a scar on his mind and he did not attend school for the next three days. His parents approached the school trustees and pressured them to take action against the bully before their son could resume school. The bully's parents were summoned. This was not the first time they were called in, as there had been multiple complaints against him. But this was the first time they were facing the trustees, principal, teachers and other parents together.

Parth Lakkad | Amey Mansabdar

Parth Lakkad | Amey Mansabdar

Parth Lakkad, the bully in question, wells up recalling the incident. Lakkad is 21 now and is preparing for his chartered accountancy exams. A few months ago, he landed a teaching job at a nearby coaching class, thanks to his “exceptional mathematical and accounting skills”, he reveals. Every day, he leaves home in the morning to go to the neighbourhood library, where he spends close to 12 hours studying. We meet over breakfast at a cafe in Mumbai on a pleasant weekday morning. He appears fresh and cheerful, not too overwhelmed by the impending exams, just a fortnight away. He is confident of clearing the exams―his second attempt at the intermediate level. Lakkad was always a good student, scoring 89 per cent in class 10 and 92 per cent in class 12. Merwyn D’Souza, who was the vice principal when Lakkad was in school, remembers him as an academically bright student. But Lakkad was also known to be the “bully whom everyone feared”. “I was the most notorious student in my school,” recalls Lakkad. “I would instigate some boys by passing comments and then get them into trouble. I remember once getting a boy suspended from school, too. We were a gang of three, notorious for causing trouble all the time. I was a big bully in school. I would repeatedly get a boy beaten up by others in class only because I did not like him. Those who had to share the bench with me were afraid of coming to school because of me. I was frequently suspended from school.”

Memories of his higher secondary school days are clear. “I have stored them in a corner deep inside; they keep raising their head every now and then. I can never forget all that I did,” says Lakkad. But he admits that he is a vastly different person today. He almost wants to dissociate himself from the teen he was. “I hit, made up lies about some boys, spoke trash to their face and behind their back, made their day awful. I think I was short-tempered and would consider everyone on my radar an enemy. I had violent tendencies,” he says.

Lakkad was sent for counselling and therapy in school. “The therapy helped me a lot, I think, because nobody scolded me or howled at me,” he recalls. “They were appreciative of me, highlighted my positives and that validation helped. Their words were soothing―my counsellor told me I was intelligent and smart and I could even become the prime minister if I channel my energies positively. And that nobody in society would ever accept a bully like me no matter how good I was in academics.”

With that message in mind, Lakkad left school but has been in regular touch with his counsellors because he needed their guidance often. D'Souza, who also counselled Lakkad, tells THE WEEK that he has seen drastic change in his former student. “He is more mature, understanding and sure-headed lad and is a complete antithesis to his younger self,” he says. “One reason is also that he has found a sense of purpose now, he wants to make something of himself and he is moving ahead with that single-minded goal.” However, it wasn’t easy. Just last year, Lakkad found himself “completely messed up”. “I fell into bad company, and validation suddenly became crucial to me,” he says. “So this group of friends made me do things that I wouldn't have done otherwise, just so that I could be 'qualified' to be with them. I was so involved, that's when I failed in my first attempt at the intermediate level exams. It was my first failure, and the shock was immense. That is when it hit me hard that something was not right and I sought therapy again. I think I could also see the change in me when I stopped giving in to peer pressure and completely cut off from that toxic group of friends. Even today, my anger issues do flare up, but I am getting in control.”

Six months ago, Lakkad met Vishakha Punjani, clinical psychologist and psychotherapist at Astitva Clinic and at Sion hospital in Mumbai. “His mother had called up saying he was exhibiting symptoms such as easy aggression, guilt, crying spells, hitting and slapping, throwing things, abusive language, use of substance and lying, and this behaviour was hampering his day-to-day life,” she recalls. “His friends were not very appropriate for him, and slowly and gradually he realised how people’s acceptance, validation and judgement really mattered to him. He came to me very willingly and told me how he felt like both a victim and an accused for his behaviour. So, the most significant aspect worth noting here is that how as he grew up, he became a victim of bullying―something he was accused of in school. We call this a loop, seen frequently.”

What Punjani found heartening was Lakkad willingly opting for therapy and putting it into practice. “He now understands that he needs to work towards things that are under his control and let go of those that are not,” she says. “I think in that aspect, he has become incredibly self-aware. He has a grip on his impulses and knows how to channel his energy.”

While Lakkad’s bullying tendencies peaked during his high school years, such behaviour can show up quite early. Mohini Khurana, a mother of two in Delhi, tells THE WEEK about her seven-year-old daughter's predicament after coming home from school. She said her friend told her to bring two chocolates to school the next day if she wanted their friendship to continue. “My daughter was anxious and begged me to buy the sweets, only so that she doesn't lose her friend,” says Khurana. Punjani says that's the beginning of being bullied. “Once you give in, they understand that you are the weaker one,” she says.

Shweta Singh, research scholar from Benaras Hindu University, explains how bullying is an intentional and repeated action to harm or make others feel low, and the victim is unable to defend himself. In her research paper, she writes that the prevalence of bullying is very high in India―approximately 50 to 60 per cent.

A recent study in Finland takes this further as it establishes that children who bullied others at the age of eight or nine are more likely to commit violent offences by the age of 31. This was shown in a nationwide birth cohort study conducted at the Research Centre for Child Psychiatry at the University of Turku. Boys and girls who were frequent bullies had an increased hazard for violent offences as opposed to children who never bullied others. Boys who bullied frequently were more likely to commit violent offences compared to those who bullied sometimes.

The relative hazard for boys who were frequent bullies to commit a severe violent offence such as homicide or aggravated assault during the follow-up period was almost three times higher than for boys who never bullied. The study considered the background factors of socioeconomic status and possible childhood psychopathology. The association between bullying and violent offences remained even when the data was controlled for parental education level, family structure and possible child psychopathology. “Our study showed an association between bullying and violent offences both in men and women. These findings further confirm the previous notions that preventing bullying could possibly decrease violent offences,” said researcher Elina Tiiri. The research project aimed to establish a connection between childhood psychosocial problems and mental health disorders, substance abuse issues, mortality, self-harm, criminality, life management and marginalisation in adulthood.

“The main factors that lead to disturbed behaviour are home atmosphere not being conducive, financial concerns, socioeconomic factors, no support from close ones, parental neglect and lack of communication,” says Punjani. “It is crucial for parents to spend quality time with their children because if they don't the child will learn to suppress his or her emotions and vent out in different ways.”

A victim is as much prone to self-harm as is the perpetrator, say experts. Recently, a 13-year-old boy was found hanging in his bedroom by his father. The boy reportedly left a note, saying that he could not bear the “harassment and humiliation” by his teacher and classmate over his poor academic scores. His message―“Papa, please don’t shout at my sister”―speaks at so many levels, including that the parent was strict and difficult to confide in. Yashi (name changed), a class 9 student in one of the posh schools of Delhi, confesses to being bullied in class but admits she has no agency on either walking out on her friends or calling them out for what they do. “I think it is fine. I don’t like it, but it’s okay. They are my friends after all,” she says.

This is indicative of how students consider this as normal behaviour and do not see anything wrong with it. This kind of a thought process emanates from a desperate need for validation and acceptance which a child is unable to get at home and craves for from outside, say experts. Although schools have been undertaking regular counselling and awareness sessions on identifying bullying, the home atmosphere has to be conducive and must facilitate a loving upbringing for a child to grow with a positive outlook towards life.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Of late, bullies have found a virtual playground. The anonymity online has given a free rein to cyberbullies, who many a time turn out to be school students. Kalpana Iyer fumes when talking about her 14-year-old daughter Aadya being almost cyberbullied last year. When the family moved from Malaysia to Mumbai, Aadya was 11. At her new school, she was sidelined by a group of girls. But one girl extended a hand of friendship and Aadya grabbed it without judgement. Last year, a new girl joined her class and Aadya became friends with her, too. “But then something happened towards the end of last year when the first girl and my daughter stopped communicating because the former said something wrong about the second girl, and my daughter stood by the latter. And so, the former friend felt slighted and targeted my daughter on Instagram and WhatsApp,” says Iyer.

Aadya, like any child her age these days, has multiple accounts on Instagram. Only one of her three accounts is public; the other two are private. In one of her private accounts, Aadya started getting messages from a boy. “The messages were flirtatious, invitations for friendship, comments on her looks and body type,” says Iyer. “My girl must have been attracted to the boy. But soon she realised that the boy’s way of texting was similar to her former friend’s. Aadya even confronted her, but the latter denied it.”

Even as the ‘boy’ kept chatting with Aadya on Instagram, she came to know about a WhatsApp group involving her. “My daughter received 48 screenshots of the conversations happening in that group, shared by a girl who was a part of that group but had later exited,” says Iyer. “The screenshots showed how the group members were scheming to bully my daughter through a fake ID and getting her into a sex racket. All this by her own classmates.”

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

The incident had a deep impact on Aadya, affecting her studies and social life. She turned rebellious, lost her appetite and went into a shell, says Iyer, who then approached the school counsellor. The counsellor told Iyer that this was not the first complaint against Aadya’s former friend. On further probing, the counsellor informed Iyer that the girl was suffering from anxiety because of her parents’ broken marriage.

Professor of law Debarati Halder, founder of Centre for Cyber Victim Counselling, says that among teenagers bullying often takes the form of sexually explicit language that includes not just verbal communication but non-verbal and non-textual communication in the form of photographs, GIFs, memes and emojis. “One main problem I have noticed is how parents normalise it by shaming their children who are victims of cyberbullying by saying things like, ‘you’re not strong enough to face it’ or ‘you could have avoided it’ or ‘you need to develop a thick skin’. That way they are actually pushing their children towards a dark hole,” says Halder. Schools, too, shirk responsibility in case of cyberbullying to save their reputation. Instead of belittling victims or ignoring instances of cyberbullying, the right questions need to be asked―when you were being bullied, did you feel worthless, harassed? Or, did you feel like hitting that person back? Or, did you feel like hurting yourself? We fail to ask these questions and eventually in the mind of the victim, the bully's behaviour becomes normalised.

“In many of these cases I find that the child is coming from a home where bullying takes place on a daily basis between the parents,” says Halder. “So a bully does what he or she does not just for sadistic pleasure but to gain a dominant position among peers.” Especially in the area of cyber bullying, the deterrence is very low because the child feels he or she is not causing any physical harm and also because there is seldom any action taken by schools.

Halder recounts an incident involving a high school girl who was being bullied online. She was unaware that the person behind it all was a boy from her class. “He used foul language and explicit comments and harassed her with multiple messages every day. At times, even at night,” says Halder. “When her parents tried to confront the school about it, the school as usual did not take the matter seriously. Terming it an issue of discipline, they punished both the boy and the girl, thereby implying that both the victim and the perpetrator were at fault here. Generally, it is observed that schools tend to shirk the responsibility if the platform on which the bullying takes place is not hosted by the school and is not monitored directly by the teacher. But if the parents persist with the case, at most, schools admonish the children or suspend them for a few days, the way it happened in this case.” This attitude by the school authorities, says Halder, is encouraging for the bully because they feel complaints against them are resulting in no significant punishment. But the victim continues to feel threatened and loses morale. “As there is no anti-bullying law in India at the moment, it is very difficult to impose a severe punishment on the perpetrator,” says Halder.

This, despite the fact that as per official statistics, India leads globally in the percentage of children reporting cyberbullying. As per Chandrashekhar Pandey, programme director with ChildFund India, “Forty-six per cent of children in India reported cyberbullying by a stranger, compared to 17 per cent globally. And, 48 per cent reported cyberbullying by people they know, compared to 21 per cent of children in other nations. Spreading false rumours, being excluded from chats or groups and name-calling were the top three types of cyberbullying reported in India.”

Experts attribute a noticeable rise in cyberbullying in India to the pandemic, which led to children and adults both taking to online learning and an increased social media usage that came with the mandate of staying indoors. And with India ranking among the highest number of internet users in the world, tackling the negative consequences become a challenge. “Cyberbullying can manifest itself in a number of ways, including sending unpleasant messages, publishing humiliating comments, disclosing personal information, and circulating rumours,” says Pandey. “It is difficult to recognise and prevent since it can occur anytime, any place and to anybody, unlike conventional bullying. And the high rate of cyberbullying in India is partially due to a lack of knowledge and instruction regarding online safety. Many children and adolescents aren’t aware of the dangers of talking to strangers online or disclosing personal information online.”

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

As per a cross-national study related to cyberbullying released by the World Health Organization in March, titled ‘Health behaviour in school-aged children,’ the increasing digitisation of young people's interactions is the main cause of cyberbullying. “With young people spending up to six hours online every day, even small changes in the rates of bullying and violence can have profound implications on the health and wellbeing of thousands,” said WHO regional director for Europe, Hans Kluge, highlighting self-harm and suicide as possible consequences.

As per the WHO report, younger adolescents are particularly at risk of being bullied. The prevalence of bullying others was highest among boys at age 15 and girls at age 13. While the proportion of boys and girls who are victims of traditional bullying is similar, girls are more likely to be cyberbullied.

The trauma which a victim carries is immense and takes years to get over. Dr Manoj Kumar Sharma, professor of clinical psychology, NIMHANS, Bengaluru, recalls the case of a girl, who as an 18-year-old, became friends with a guy online. “Initially, she enjoyed the online conversations. Then they decided to meet in person,” recounts Sharma. “But when they met, she did not appreciate the overall experience and decided to exit the relationship. Then this person started bullying her and threatened to share her chats. She did not want her parents to know as they were from a modest, middle class background. She took almost one and a half years to reveal her ordeal to her parents, who then approached us. Today, she is 21 but the trauma of the bitter experience she had as a student continues to haunt her. She is taking therapy for depression and stress.”

If increased screen time and lack of awareness about online safety with working parents who are busy all day are at the root cause of this problem, then how does one address it? When THE WEEK asked Lakkad about his knowledge regarding online safety, he said that ever since he got his own smartphone at the age of 13, he has been practising self-regulation. “My day begins with browsing on my phone, and my mother hates it,” he says. “But I remember doing this ever since I was in school because school began in the afternoon and I was allowed screen time in the morning. I know there are certain things I must not watch, but I apply my own agency and decide what’s good and what's not. I monitor my own time and simply cut off from the phone after about two hours of continuous screen time. But I cannot give that up because after a long day of studies, I need a break and that's how I have known to entertain myself for the longest time. I can't change myself now.”

According to bullyingstatistics.org, when it comes to cyber bullying, statistics show most cases are taking place on popular social media sites such as Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter. In 280 characters or less, teens can make hurtful and emotionally scarring comments about fellow schoolmates on Twitter. On Instagram, they may leave bullying and mean comments on photos, including body shaming or fat shaming comments. On Facebook, the messenger app makes it easy for kids to send cruel messages back and forth, creating groups where teens can gang up on one another. On Snapchat, known for sending easy-to-delete photos, teens can pass around inappropriate photos of classmates or hurtful images that can fall under various forms of bullying.

One useful tool to help combat social media bullying is the block feature to bar followers on the various platforms. On Instagram, users can turn off comments on posts, which makes it easier to prevent users from leaving harmful comments, making threats or participating in body-shaming commentary. On Twitter, it is more difficult to do so as profiles cannot be made private, but Facebook offers tight privacy settings for users, which makes it easier to keep bullies out. On Instagram, one can also change their profiles to private.

Recognising it as an issue of concern, the Union home ministry launched the Cyber Crime Prevention Against Women and Children initiative, which aims to provide a secure online environment for children. The initiative provides a helpline and a portal where children can anonymously report cyberbullying. The ministry has also launched National Cyber Crime Reporting Portal to enable citizens to report cybercrimes, including cyberbullying and receive prompt action.

How to help bullies

Research finds that bullies have a distinct psychological makeup. They lack prosocial behaviour, are untroubled by anxiety and do not understand others' feelings. Those who chronically bully tend to have strained relationships with parents and peers.

As a psychotherapist, my approach would focus on empathy, self-reflection, and behaviour change.

1. Establish trust: Create a safe, non-judgmental space for the bully to open up about feelings and actions.

2. Identify motivations: Explore the underlying reasons for their behaviour, such as insecurity, peer pressure or past trauma.

3. Raise empathy: Help the bully understand the impact of their actions on others, encouraging perspective-taking and compassion.

4. Recognise patterns: Assist the bully in acknowledging their behaviour patterns and how they can be hurtful.

5. Develop self-awareness: Encourage self-reflection, helping the bully recognise their emotions, triggers and choices.

6. Teach healthy coping mechanisms: Introduce alternative ways to manage emotions, such as mindfulness, communication or problem-solving skills.

7. Foster accountability: Support the bully in taking responsibility for their actions, making amends if possible, and committing to positive change.

8. Monitor progress: Regularly assess the bully's behaviour, providing guidance and encouragement throughout the transformation process.

9. Address underlying issues: If necessary, address underlying issues like trauma, anxiety or depression through evidence-based therapies.

10. Promote empathy and kindness: Encourage the bully to engage in acts of kindness, volunteering or empathy-building activities to solidify positive change.

Remember, helping a bully requires patience, understanding and a non-confrontational approach. By addressing the root causes and promoting empathy, we can support positive growth and behaviour change.

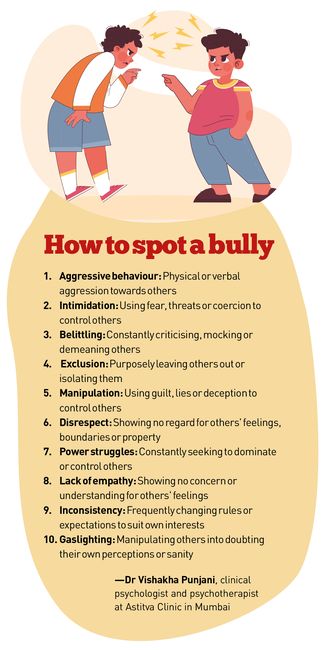

―Dr Vishakha Punjani, clinical psychologist and psychotherapist at Astitva Clinic in Mumbai