John McEnroe’s favourite quote in McEnroe, the bracingly honest documentary that released on July 15, comes from his wife, Patty Smyth: “I married a bad boy who became a really good man.”

“That was really beautiful,” McEnroe, 63, says with a grin via Zoom from his home in New York. Many would agree with Smyth. McEnroe has gone through a striking transformation in the past 40 years, from the “you cannot be serious” tantrums that earned him the nickname “superbrat” to his present status as one of sport’s most cherished elder statesmen. His candid and insightful commentary, delivered in that swaggering drawl, is one of the joys of watching Wimbledon.

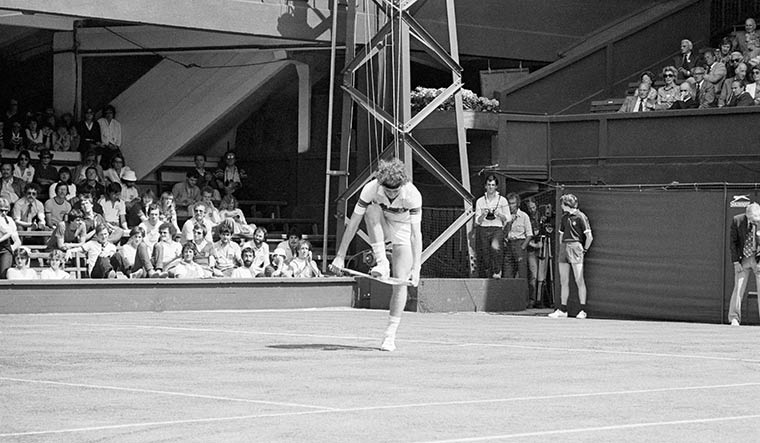

McEnroe’s journey is charted with a refreshing lack of sycophancy in the documentary by Barney Douglas, the director who made The Edge, a similarly clear-eyed film about the England cricket team. We see him combine flair, nous and stroppiness to win three Wimbledon singles titles in 1981, 1983 and 1984, becoming the best player in the world. We revisit his demons, his rivalries with Bjorn Borg and Jimmy Connors and his tempestuous, drug-addled first marriage to actress Tatum O’Neal. And we find him now in a state of relative harmony, hanging out with Smyth and his five children, aged between 23 and 36.

A stirring tale of redemption? This being McEnroe, it is not quite that simple. “I didn’t think I was that bad a boy in the first place. People got me all wrong,” he says, looking lean and hip in a black jacket over a white T-shirt. A big reason why he became a bête noire at Wimbledon, he agrees, was because he was such a bad fit with the All England Club, then one of the stuffier corners of the British establishment. “I grew up in Queens in New York, and there were people yelling and screaming all the time,” he says. “It was a loud dinner table. And it seemed normal.” When he first played Wimbledon in 1977 it was his first time overseas. “I was, like, ‘Oh my God, these people are so polite. It’s so quiet here.’”

He accepts, though, that he exacerbated the situation. “You sort of feed into this villain thing, maybe unbeknown to yourself, and then it becomes this out-of-control monster. People started to recognise me—‘Are you that brat guy?’—and it completely changed my life. I was, like, ‘They don’t understand me, I’m a nice guy.’ But of course I wasn’t real nice on the court at times.”

Watching Connors, who cold-shouldered him before one of their early matches, helped him to learn how to be a “prick” to opponents. “Connors isn’t that big a guy, I’m not that big a guy, you have to come at your opponents with an intensity that radiates off your body,” McEnroe says. “That’s what intimidates them.”

He contrasts that with today’s top players, many of whom “seem like unbelievably nice people. Rafael Nadal has claimed he’s never broken a racket in his life.” Yet Nadal and Roger Federer are not representative, he thinks. “Generally, I think people are, as far as tennis goes, more like me and Connors than Borg, who never showed any expression. It’s a very frustrating game that it’s hard not to get emotional about. I’d be, like, ‘I’m gonna go practise and be like Borg for two hours,’ and that would last, like, five minutes. It just wasn’t in my DNA.”

We are speaking before the Australian Nick Kyrgios becomes the talk of Wimbledon after a vitriolic match against Stefanos Tsitsipas of Greece in which Kyrgios verbally abuses a line judge and Tsitsipas hits a ball into the crowd. After the match Tsitsipas calls Kyrgios an “evil bully”.

Surely part of McEnroe would approve. “Grand Slam tennis is not a popularity contest,” he later says in a trailer for the BBC, adding of Kyrgios: “Yes he did go too far. If he’s allowed to get away with it then he gets away with it.” Well, both players were fined, but Kyrgios was ranting away again in the Wimbledon final.

Have his outbursts got so much attention because tennis has become too boring? In his heyday, McEnroe says, “it felt like the inmates were running the asylum—me and Connors and [the temperamental Romanian] Ilie Nastase. And I think in the late 1980s they tried to stifle some of the personality, like that was bad for the game. Which I completely disagree with, by the way. Pete Sampras is one of the all-time great players, but he’s not going to light it up necessarily, personality-wise. In a one-on-one game, you need personality.”

His best match, he says, was the epic Wimbledon final he lost to Borg in 1980, recreated in the film Borg vs McEnroe, while his best performance was beating Connors “one, one and two” (6-1, 6-1, 6-2) in the final in 1984. “It felt like the ball was this big (he holds his hands a foot apart) and I could do anything with it.” There is no false modesty—he talks about “taking the game to another level. I’d sort of mastered what I idolised about Rod Laver (the Australian champion of the 1960s) and I was three or four inches taller. The mistake I made is I sat back and went, ‘Let’s see what they’re going to do,’ instead of, ‘I gotta keep getting better.’”

Borg retired in 1982 at 26. Had he carried on longer, would that have driven McEnroe to more than his three Wimbledons and four US Opens? “Absolutely. It would have been better for me and the game. It was just a huge hole. Novak Djokovic and Nadal have played 59 times now, which is a crazy amount of times. Borg and I only played 14. It was a damn shame.”

Also looming large in the film is McEnroe’s father, John, a former employee of the US Air Force who became a lawyer and his son’s manager. He does not cut a cuddly figure. “When I was born, he was refereeing a basketball game on an army base,” McEnroe says. His mother, Kay, does not sound like a softie either. “I broke my arm when I was eight and she said, ‘Here’s two aspirin, you’re fine.’” McEnroe thinks he overcompensated for that stoicism when he separated from O’Neal. “My kids said, ‘Dad, you gotta stop crying now.’”

His father pushed him hard, which may be why McEnroe did not feel euphoric when he was at the summit of tennis in 1984-1985. “I’m the greatest player that’s ever played at this point,” he says in the film. “Why did that not feel that amazing?” You certainly cannot put all his troubles down to New York abrasiveness. “I’ve had plenty of therapists,” he says. “Some of them court-appointed”— he was ordered to see an anger-management counsellor after his divorce from O’Neal. The film has been “therapeutic in some ways”, helping him to come to terms with the fact that he did not say goodbye properly to his dad before he died in 2017: “That send-off still feels empty to this day.”

Smyth suggests intriguingly in the film that McEnroe could be on the autistic spectrum. His ability to excel in one skill at the exclusion of others fits that theory, as does his irascibility when things do not go to plan. “It’s safe to say that I’m probably somewhere around there,” he says. You could also point to his facility in maths at school and what he sees as his biggest flaw, a lack of empathy. Although I’m not sure the latter is true, given the way he can put himself in others’ shoes when he commentates.

He can also be outspoken as a pundit, having called Boris Becker’s imprisonment a “travesty” and urged America to change its “ridiculous” vaccine laws, which may prevent Djokovic from competing at the US Open. He says he disagrees with Wimbledon’s decision to ban Russian athletes this year: a player such as Daniil Medvedev, the world No 1, is “probably not too happy about what’s going on [in Ukraine]. But if he says anything, his friends or his family could be thrown in prison for 15 years.”

Electronic technology means that today’s players can be more certain whether the ball really was on the line. If McEnroe envies that, it is the opposite with social media. He watches with bemusement as his children chase likes. “Jesus Christ, that’s all they do. It’s worse than being a heroin addict. If I’d been 20 years old and on social media and the press had gone after me, I’d be losing it. I think I might have thrown some things out there that I’d regret.”

Is there anything he would have done differently in his marriage to O’Neal? “Of course. Are you kidding?” They had children too young, he thinks. O’Neal was 22 when she had their first, Kevin, with Sean and Emily following within five years. “It was a little too much to expect.”

Then there were the paparazzi. “You’d be on page six of the New York Post or something.” The film shows him having an altercation with photographers: “I’m taking a shit—you want a picture of that?” His creativity and volatility were suited to the entertainment world, though. His friends include Keith Richards (“If you’re used to working crowds you have something in common,” Richards says in the film) and Chrissie Hynde, on whose debut solo album McEnroe played guitar. He talks in the film about trips to Studio 54 and we see him and his friend, the tennis player Vitas Gerulaitis, being interviewed on MTV while clearly stoned.

Imagine Nadal, Federer or Djokovic doing any of that stuff. Maybe they have the right idea, though, because he happily concedes they are the three best players in history. “Roger is the most beautiful player I’ve ever seen. He’s like an updated version of Rod Laver. I’d never seen anyone that tried harder than Jimmy Connors but Nadal has succeeded in that. Djokovic is like the human dartboard, which I can relate to.” He gives Nadal “the slight edge”, although Djokovic has made the margin even finer by winning Wimbledon after the Spaniard pulled out injured.

McEnroe and O’Neal divorced in 1994 and four years later he was granted sole custody of their children because of her addiction to heroin. How are relations with her now? “We have a difficult time communicating,” he says. “I’m not gonna sit here and pretend it’s great. When I hear people say, ‘We’re divorced and I got remarried and my ex- comes on trips with us and it’s great,’ I’m, like, ‘How’s that even possible?’”

In 1997 he married Smyth, a Grammy-nominated musician not to be confused with Patti Smith. “I was 35, I’d just gone through this horrific divorce, I don’t want any relationships. And then all of a sudden I’m with Patty and I’m, like, ‘Oh my God, I’m getting a second chance. Do not blow this. Don’t be an immature idiot.’”

He hasn’t blown it so far. He and Smyth have two daughters, Anna and Ava. Other than commentary, he is “sort of searching” for something to do. He once considered going into politics as a Democrat, “but I came to my senses, because that is just totally nuts. I’m not cut out for that.” Whatever he ends up doing, the demons have quietened. “I feel proud of the direction I’ve gone in, what I’ve learnt from my successes and failures as a player, as a husband and as a father,” he says. “Ultimately, you have to ask yourself: how comfortable do I feel as a human being? I feel pretty good.”