So, you have lined your kitchen with organic food and whole grains; you’re hooked to yoga; your persistent new year resolution is to walk more and drink less; and you turn to the internet for every little health niggle that comes your way. But, how medically literate are you?

Scientifically: dismal.

According to a 2018 paper in the Indian Journal of Community Medicine, while studies on medical awareness are many and diverse, poor medical mindfulness cuts across regions and classes, thus keeping the lifespan of Indians shorter than what it could be.

One such study in Karnataka, for instance, found out that only a third of mothers, across two generations, had knowledge about breast feeding. Another concluded that while more than four in five respondents in Kerala knew about oral cancer, fewer than three could pinpoint the exact cause. Yet another one, which covered Chandigarh, Tamil Nadu, Jharkhand and Maharashtra, revealed that less than half of the sample population knew anything about diabetes.

What makes us so poorly informed? While inadequate access to health care, deficient manpower and the cost of quality health care are reasons beyond us, a huge role in this knowledge lag also results from our dithering in questioning doctors, our surrendered acceptance of what they tell us.

Look around, someone you know might have been pushed into surgery that a second opinion concluded was not needed. Someone might be on medication prescribed years ago by a doctor, unaware that age, hormones, changing lifestyles, comorbidities and the like require a change in medication or dosage. A third someone might only consult the neighbourhood chemist for ailments.

We are, more often than not, in awe of our doctors. Yes, they have very special skill sets. And yes, we place our wellbeing in their hands. But then, we also place our lives in the hands of pilots when on a flight. At the end of it, both are service providers. And neither is a demigod.

As with other professionals, good communication is vital to healthy doctor-patient relationships. Dr Sushila Kataria, senior director of internal medicine at Medanta, Gurugram, lists a host of challenges that keep patients from conversing with their doctors adequately.

“Patients might lack awareness about their condition, leaving them unsure of what questions to ask,” she says. “They might fear that their questions could come across as trivial, leading to potential embarrassment. They may worry that asking too many questions could annoy the doctor and potentially affect the quality of their treatment.” Especially when it comes to surgical procedures, this handicaps patients with little understanding of the procedure, its potential complications and alternative treatment options.

Another point she underscores is the exercise of caution when gathering information from the internet and uncertified sources. “Excessive and unverified information can lead to confusion,” she says. “In some cases, patients may unnecessarily delay procedures due to excessive scepticism about the medical system. Striking a balance between seeking knowledge and relying on trusted sources is crucial.”

Remember, the internet works around codes, not around consideration for us.

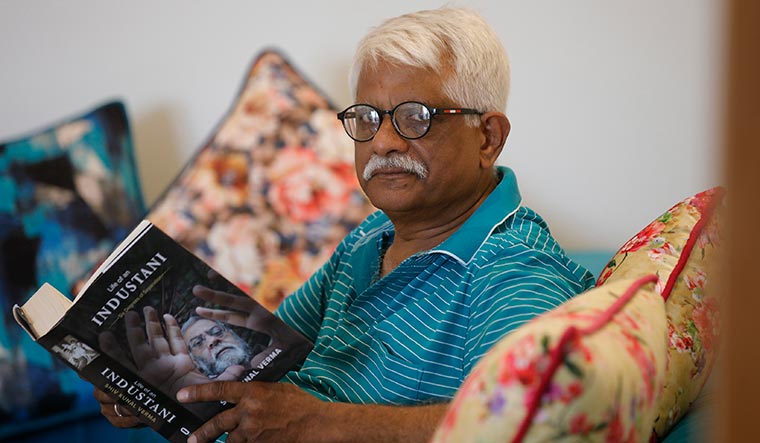

Dr Pradip Tiwari, a plastic surgeon who recently retired as senior consultant at the Burn and Plastic Surgery Unit at the Dr Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Hospital, Lucknow, started his career in the state’s Provincial Medical Services in a neighboruing district of Lucknow. Despite the fact that Tiwari holds an MCH, the highest degree in surgical science, he was reduced to being a general practitioner for the first eight years of his professional life. “When a doctor’s skills are not optimally utilised, his level of interest in patients may go down,” says Tiwari. His observation is significant for the government health care system. Less than a third of India's population relies on it, but the private system cannot match its reach.

Dr Pradip Tiwari | Pawan Kumar

Dr Pradip Tiwari | Pawan Kumar

When Tiwari was posted in Lucknow, most of his patients were those with congenital deformities or post-traumatic problems (such as scars from a burn injury or accident). As a result, Tiwari’s cosmetic surgery skills were barely used for most of his career. For a brief period that he tried private practice, he bought what was perhaps Lucknow’s first liposuction machine, but was clear about pegging patient hopes pragmatically.

“It is very important for a patient to ask about realistic results and a doctor to not build unnecessary expectations,” he says. “Liposuction, for instance, is not a cure for obesity as the number of fat cells remains constant throughout life. We should tell patients what surgery can achieve and then encourage them to think and ponder before opting for it.”

He also emphasises the need for patients to be completely honest with their doctors. There are patients who can get stuck on one question; for example, will my scar completely disappear? (No, it won’t, though a surgery will give you a smaller, cleaner scar). For such patients, Tiwari suggests a psychiatric evaluation. “If a patient is persistent to the point of being unreasonable, a doctor should list the complications and generally say no. Some patients only want a doctor to say what they want to hear,” he says.

Dr Joy D. Desai, director of neurology at Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre in Mumbai, adds taboo to the list of reasons patients do not open up. In his speciality, for instance, epilepsy and seizures come with social stigmas, a popular one being that a person thus afflicted is seized by evil spirits. “A patient might allow the caregiver to do most of the talking and that builds a barrier between the doctor and the patient,” he says.

Desai also touches upon the issue of our deep respect for doctors. “We have been taught that respect is inherent in the position one occupies,” he says. This is not an ideal relationship between doctors and patients.

Among the questions that Desai lists as must-asks for patients are: the implications of their symptoms, the nature of the disease, and the nuances that determine treatment outcome. “When investigations are asked for, the absolute validity vis a vis the potential expense likely to be incurred should also be discussed,” he says. “For chronic and neurodegenerative disorders, counselling on future trajectory of the illness is also mandatory. An introduction to potential caregiver burden is a necessary component of this communication.”

Desai also speaks of the need for better bedside manners for doctors. It could come perhaps from some background in humanities, he says, but then that would extend the duration of a doctor’s training. Social/softer skills could be a part of the continuous skill/knowledge upgrade that doctors put themselves through conferences, seminars and the like.

Dr Shrikant Srivastava

Dr Shrikant Srivastava

We also need to stop banishing some specialities to realms of vanity or magic. Ruby Sachdev, aesthetic physician and founder of Skinnfit Medspa at Gleneagles Global Hospital, Bengaluru, says that we cannot disregard the fact that looks play a part in enhancing self-confidence and thereby ensuring mental wellbeing. “Someone might aspire to become a CEO and looks might play a role in the image that position must project,” she says. “As doctors we should be non-judgmental, but realistic. In our profession, we primarily focus on prevention, enhancement or restoration. It is important to note that while certain features can be enhanced, they cannot be replaced.”

Sachdev does not hesitate to recommend a pause to clients who seem to get addicted to procedures. “I always emphasise that procedures in cosmetology are not emergencies,” she says. “I advise clients to take their time, sleep on it, not rush into decisions, read about the procedure, think about it, and then return with any questions they might have.” One of the most important of these questions is the downtime required after a treatment. One cannot, for instance, trot out into the sun right after a skin-resurfacing session.

Dr Shrikant Srivastava, professor, department of geriatric mental health at King George’s Medical University in Lucknow, is a specialist for a relatively less known branch of medicine. Being medically literate would thus include an awareness of new specialities and medical technologies that can improve the quality of our lives.

Mental illnesses of the old is at such an infant stage (KGMU introduced the country’s first department just 20 years ago) that only five super specialists in it are produced in the country every year. Srivastava stresses the supreme importance of a patient’s choice in treatment. “We can only offer advice for a management plan. It is up to the patient to accept or reject it,” he says.

In a speciality where there are no prescribed, objective tests to measure illness, and where ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ lie in a continuum, it is of paramount importance for the doctor to make a patient open up. “If your patient is comfortable, the information will automatically come. In a consultation session of at least 30 minutes, I will spend 10 minutes explaining to the patient what I am prescribing and why, and their role in the management plan. Every doctor wants his treatment plan to work. A plan which is explained to a patient, in a language s/he understands, has greater likelihood of compliance,” he says.

The doctor draws attention to the opposite ends of mental health seeking behaviour―the west where three days of a dip in mood would send one to a psychiatrist, and India, where symptoms are only noticed when they become too prominent to ignore. The balance lies somewhere in between.

As for the need for soft skill training, Srivastava believes that the only expertise required are those in everyday use. “The patient should be treated as an equal,” he says. “Both parties should speak in a conversational, not confrontational/didactic manner. You must follow the same principles you would in everyday interactions. Give each other space, respect one’s privacy, ask questions about the topic under discussion and listen, not just hear.”

So ask away, readers. You have nothing to lose but your ignorance. And it will get you no reds in the report card of life.