Wade Warren works as a product manager for a financial technology company. He is 28-years-old, bearded, bespectacled and lives in a small apartment in Brooklyn, New York. Every evening he puts on a special pair of goggles designed to block the short-wavelength, high-energy blue light that is emitted by his smartphone and laptop screens and, in so doing, he enhances his ability to fall asleep later. He sleeps on a more than Rs 2 lakh temperature-controlled mattress, which helps keep his core cool, which in turn stimulates melatonin, and, thus, ensures a better night’s rest. When he wakes, he will flick on the large 800W floodlight he keeps in a corner. By doing this, Warren suppresses his melatonin production and signals to his body that it is time to be awake. It also, he believes, improves his gut microbiome.

He adheres to a diet that is high in protein, low in carbohydrates. He also does a lot of other specific things to improve his “efficiency and effectiveness”. But you get the gist.

Warren had not thought to do any of this until one evening when he stumbled across a podcast hosted by Dr Andrew Huberman, a neuroscientist and professor at Stanford School of Medicine. He was drawn in by Huberman’s ability first to present complex scientific or biochemical concepts in a way that made sense, and then to provide listeners with advice about how to use this information, whether to do with fitness, mental health or behavioural change.

It was, essentially, self-help with science, and this pleased Warren. He became a devotee of Huberman, whose appeal is only enhanced by his incongruous appearance. With his beard, broad chest, meaty hands and piercing dark eyes, the 48-year-old Californian appears more like an Iron Age warlord than a neuroscientist. Today, the Huberman Lab advertises itself as the world’s most popular health podcast. He has more than six million Instagram followers, another five million on YouTube and several million across other platforms. Recent allegations made by a number of former partners that he is guilty of serial infidelity and controlling behaviour, which he denies, are unlikely to dent these numbers much.

Huberman is one of a number of popular online male personalities who are offering us the chance to become healthier, more efficient, better optimised human beings. If one of the dominant trends of the 2010s was “wellness” ― think Gwyneth Paltrow, Goop, crystals, healing energies, vague spiritualism and an endless list of alternative health practices made commodifiable and Instagrammable―then what we are seeing now is the emergence of something quite different. It is, ostensibly, a rationalist alternative―a Wellness 2.0―in which “science bros” offer advice founded, they insist, on research and data.

So there is Dr Cal Newport, a boyish 41-year-old computer science professor who writes popular books about focus and productivity and whose YouTube channel attracts millions of views via videos with titles such as ‘How to Reinvent Your Life in 4 Months and The Productivity System to Win at Anything’. There is Dr Mark Hyman, a 64-year-old silver fox who has developed “peganism” (a hybrid of the paleo and vegan diets), writes bestselling books called things like Young Forever: The Secrets to Living Your Longest, Healthiest Life, and who has three million Instagram followers. Dr Peter Attia, 51, who specialises in the medical science of longevity, counts Elon Musk as a fan and hosts his own podcast, which delves into questions such as the metabolic effects of fructose or the dangers of poor sleep. Dr David Sinclair, a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, also operates in the field of longevity. He advocates resveratrol, a natural supplement with antioxidant properties, and claims he has “reclaimed” his 20-year-old brain despite being 54.

These men, and others, all exist in the same online ecosystem. They cross-promote, appearing on each other’s podcasts and YouTube channels. If Wellness 1.0 was fundamentally feminine in tone, then Wellness 2.0 is distinctly masculine. It co-opts the stern, didactic language of the gym or boardroom. Science bros regularly use the word “protocols” rather than “routines” or “exercises” when telling their audiences what to do. Similarly, they will describe certain mindful practices as “tools” as if they were cordless drills or angle grinders. The name of a popular online radio show dedicated to fitness and wellbeing is, simply, ‘Mind Pump’.

Brad Stulberg writes bestselling books about performance and psychology and has a background in public health. He could pass for a science bro―he is trim, shaven-headed and bespectacled―but instead it was he who coined the term “broscience” five years ago, and he regards this world with a thoughtful curiosity as well as scepticism. “This is the more masculine version of the Paltrow self-care crystal stuff,” he says. And there’s no reason why the same psychological triggers that led wellness to become such an all-consuming thing for women can’t also apply to men. “We ultimately have the same human frailties and insecurities as women. Perhaps men were just an untapped market.”

The language of “efficiency” and “performance” permeates so much science bro rhetoric, and listening to these podcasts you’re often left with the sense that the main advantage of sleeping well and feeling energised, etc, is so that you can be a better employee. There is a reason you now see men posting their impressive daily routines on LinkedIn―their gym sessions, their moments of mindfulness, their healthy lunch recipes―and it’s because they believe it shows them to be better professionals.

Like Wade Warren, Michael Fields is another fan of Huberman. He is 27 and, having worked as a technical recruiter, he made the switch to become a fitness coach as well as an online trainer. Fields says that the vast majority of his clients are young professional men and that this simply reflects the kind of people who are most drawn to Wellness 2.0.

“I definitely feel like it’s way more targeted towards young men,” he says. “I think it’s because of that constant striving for status and purpose in life.”

And it is young men stuck in sedentary office jobs, Fields continues, who most often need the tools that science bros are selling. Looking at a screen for hours will make sleeping hard. Sitting down for hours will drain your vitality. What makes it worse is that the very fact of having a career that demands all this of you makes it all the more difficult to do something about it. “They have a hard time figuring out how to incorporate habits into their daily lives while working in a corporate job.” Fields says that his male, corporate clients often insist on knowing precisely why they should, say, take cold showers in the morning. So being able to tell them what someone like Huberman has said on the subject―stuff about dopamine and boosted alertness levels, etc,―is helpful. “He provides the scientific backing.”

Many of the men within this world trade on their scientific or medical qualifications. Others have achieved their profile via a willingness to go to extremes. Dave Asprey is a multimillionaire who made his money in Silicon Valley and as founder of the Bulletproof coffee and nutrition brand. He is 50 but has regularly made the claim that he will live to 180. Today, he says he wishes to revise that claim. “I think I’ve been shockingly conservative,” he says, frowning, before breaking into a bright white smile. “I think 180 is a boring, easily achievable goal.”

Asprey has built his platform as a podcaster and self-help author around claims like these. He believes that with the proper application of cutting-edge science it should be possible for all of us to live much, much longer. I’m 42, I tell him, and in decent health. How long does he think I can expect to live? “There is no reason you shouldn’t be able to live to at least 120 and be healthy the entire time,” he assures me.

Hang on, I say. How come you get to live to at least 180 but I only get 120? He smiles again and says that it’s only because he’s been “actively managing” his age for the past 25 years.

Asprey identifies as a “biohacker”. Having spent much of his twenties overweight, arthritic and struggling with “brain fog”, he has turned his life around via a slew of different treatments and protocols, from intermittent fasting to cryotherapy and various medical interventions. He has had more stem cell injections, he believes, “than anyone out there at this point”. He recently travelled to Mexico to undergo a form of gene therapy not permitted in the US and which “takes nine years off your measured age”. He takes 84 supplements a day and says he has had his “immune system taken out, amplified by thousands of times, and then reinjected to give myself a younger immune system”. He has, he continues, done a lot of neurofeedback therapy, which, in conjunction with taking a smart drug called modafinil, has provided him with what he describes as an “upgraded brain”.

Bryan Johnson is another tech millionaire. The 46-year-old is attempting to drive down his biological age through “Project Blueprint”, which, among many other things not dissimilar to what Asprey does, involves receiving blood transfusions from his teenage son. Johnson sleeps attached to a machine that measures the number of nocturnal erections.

Asprey approaches the question of longevity with a Silicon Valley mindset. “I take control of systems for a living,” he explains in a recent appearance on the Finding Mastery podcast. And human beings are, he continues brightly, simply “meat operating systems”.

There are, however, people within medicine who find this approach more than troubling. Last year, the British cardiologist and video blogger Rohin Francis wrote in the British Medical Journal about “the problem with Silicon Valley medicine”. He points out that the “move fast and break things” mindset that underpins so much of the tech world has the potential to cause much more harm than good. The human body, he writes, cannot be compared to a machine, while the demand for profitability sees claims become ever more spurious. “Waiting for evidence gained from clinical trials is often deemed too slow a process for venture capitalists hoping to see a return on their investments, so therapies are endorsed and sold based on theoretical or mechanistic evidence,” Francis writes. “These ‘breakthroughs’ are enthusiastically promoted at events more similar to the launch of a new Apple product than a medical innovation.”

Although not everybody wants or can afford to go as far as Asprey or Johnson, the desire for control drives so much of the science bros’ present success. “I think the story of wanting to live for ever, wanting to control the controllables and wanting to ‘science’ our way out of mortality is as old as time,” Brad Stulberg says. And many of the podcasts out there today are “preying on people’s desire for control and certainty in an inherently uncontrollable and uncertain world”.

What he means is, when you find yourself listening to a podcast that delves into the minutiae of exposing your body to cold water, avoiding particular types of cooking oils or the critical importance of tracking your sleep patterns, it can become easy to convince yourself that these things are all really important. In fact, you want them to be important because these are all things you can do and thus take control of. Thanks to health-tracking smartwatches and continuous glucose monitors, it is now possible to collate and crunch huge amounts of data about our bodies. “But just because something is measurable doesn’t mean it’s important,” Stulberg says. “Like, how did we get from ‘move your body for 30 minutes a day’ to ‘measure your erections for longevity’?”

He’s not saying that all science bros are manipulative or providing misinformation. But the truth is, we already have a pretty good sense of what people need to do to lead healthy, happy lives. “We have decades of good epidemiological data,” he says, and it shows that it’s important to avoid tobacco products, not to drink much alcohol, to exercise regularly, avoid becoming obese, maintain healthy social connections and, ideally, find meaningful work.

Stulberg points out that a lot of the podcasts are sponsored by supplement companies, and one YouTube video I watched, which featured Asprey comparing his deep-breathing techniques with the host’s, featured ads for dietary supplements as well as for a “personal analysis and data-driven wellness guide”. Also, people will always want to see content they perceive as comforting. If there is somebody telling you that if you buy the right medical treatments you can live to 120, then there’s a good chance a lot of us are going to click on it.

“I don’t necessarily think there’s always malintent,” Stulberg says. “Motivated reasoning is a very powerful drug, and we can convince ourselves of anything. If you can make a lot of money from a comforting belief and create a whole business model from it, then you can start to believe it yourself.”

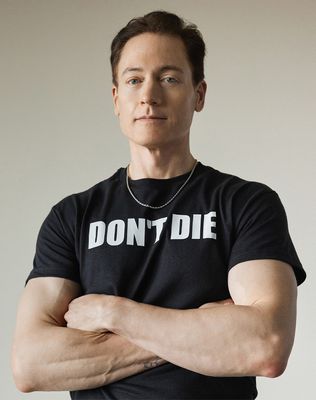

Bryan Johnson, 46

“Don’t die” is this tech mogul’s goal. He made headlines around the world last year when he said he was trying to reverse his biological age to 18. He has had some success―he claims his heart is 37 years old. Johnson made his fortune when he sold his company, Braintree Venmo, to PayPal in 2013. Since then, he has spent more than 016 crore a year on cutting-edge “age-slowing” techniques developed by his team of doctors. His routine includes getting up at 4.30am, taking more than 100 pills, bathing in LED light and sitting on a high-intensity electromagnetic device to strengthen his pelvic floor, before going to bed at 8.30pm. Johnson calls himself “the world’s most measured human”.

Power list

By Georgina Roberts

Prof Valter Longo, 56

He wants to live to 120 and thinks the secret to longevity lies in a diet that tricks your body into thinking it’s fasting. Having spent 30 years researching ageing as professor of gerontology and biological sciences and director of the Longevity Institute at the University of Southern California, he used this experience to create the Fasting Mimicking Diet or FMD. It is a low-protein, plant-based diet that includes periods of fasting, which he says will make our cells regenerate and slow down ageing.

Wim Hof, 64

Once tried to scale Everest topless to demonstrate the health benefits of being extremely cold. The Dutch extreme athlete known as the Iceman has also broken records for climbing Mount Kilimanjaro wearing only shorts, swimming 66 metres beneath ice and running a half marathon above the Arctic Circle. He has built a business empire on his cold-water method and claims that it stimulates the autonomic nervous and immune systems, which strengthens physical and mental health.

Prof Andrew Huberman, 48

Fans of this Stanford academic call themselves “Huberman Husbands” and post videos on TikTok following the elaborate daily routine he recommends. #Huberman has 78.9 million views on the platform. He dishes out this advice on his hit podcast, Huberman Lab, which often ranks as the number one health podcast in the world, and on his Instagram page (6.2 million followers) and YouTube channel (5.2 million subscribers). He is associate professor of neurobiology and ophthalmology at Stanford University, which is said to have hung up an “Authorised Personnel Only” sign to deter fans from searching for his lab.

David Goggins, 49

More than 11 million people follow the endurance athlete and former Navy Seal on Instagram, where he shares fitness and motivational tips alongside shirtless selfies. He has completed more than 70 ultra-distance races and once held the Guinness World Record for the most pull-ups completed in under 24 hours (4,030 in 17 hours). In 2020 he invented the 4x4x48 fitness challenge, where you run four miles every four hours for 48 hours as if training for an ultra-marathon.

Ben Greenfield, 43

A former bodybuilder turned “biohacker”, Greenfield went on to develop an elaborate biohacking regime to strengthen the pelvic floor, ice baths, fasting, infrared light therapy, LSD microdosing and a 034 lakh machine that heals cells, he says. When he was 40, Greenfield said he had a biological age of nine.

Dr Peter Attia, 51

This cancer surgeon turned longevity expert says that in our later years we often live with ill-health and pain, crippled by diabetes, cancer, heart disease and dementia―he calls these the “four horsemen of chronic disease”. To change that, he says we need to focus on our healthspan (the number of years we live in good health) rather than just our lifespan (the number of years we’re alive). Celebrity fans of his 2023 bestselling book, Outlive: The Science & Art of Longevity, include Gwyneth Paltrow, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Oprah Winfrey, and he hosts a podcast about longevity called The Drive.

Tim Ferriss, 46

Ferriss had a nutritional supplement business before he struck it big when he published The 4-Hour Work Week, which presented a working structure that subverted the idea of long hours as a path to success. It was followed by The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex and Becoming Superhuman and then The 4-Hour Chef. He has a long-term chart-topping podcast called The Tim Ferriss Show, for which he interviews leaders in psychology, fitness and business as well as Hollywood stars about their optimisation techniques. Ferriss has invested heavily in research into therapeutic psychedelics at Imperial College London.

Nick Bare, 33

A fitness guru who is often shirtless when he films his intense training regimes for marathons, Ironman triathlons or ultra-marathons and posts them on YouTube for his 1.1 million subscribers to watch. He started building his supplement brand, Bare Performance Nutrition, as a side project while he was serving in the US army. It sells pre and post-workout supplements and protein powders. After he left the army he created a spin-off fitness training app, which costs Rs8,000 a year. On The Nick Bare Podcast he gives tips on longevity, nutrition, fitness and “human optimisation”.

Dr Paul Saladino, 46

Graduated from medical school but lost faith in western medicine and became a “meatfluencer” known as Carnivore MD, eating meat exclusively. He claimed his carnivorous diet, which excluded all dairy, carbohydrates, vegetables or fruit, was the way to achieve “optimal health”. He published The Carnivore Code followed by a cookbook. Then, in a podcast interview last year, he revealed that after five years on the carnivore diet his testosterone levels had decreased, plus he had sleep issues and joint and muscle pain. Now he promotes an “animal-based” diet, which includes fruit, honey and unpasteurised milk.