On June 18, Japan's National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID) reported a spike in the number of 'flesh-eating bacterial infections' in the country. As of June 9, the preliminary number of cases of Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome (STSS) since the beginning of this year reached 1,019. A patient infected with Group A Streptococcus (GAS) bacteria could develop STSS, which can lead to flesh-eating bacterial infections, also known as necrotising fasciitis. This year has seen a significant increase in the spread of this rare and severe bacterial infection.

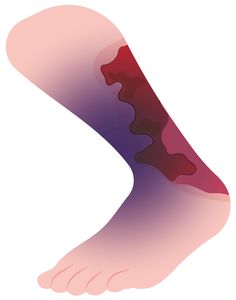

The mortality rate for necrotising fasciitis is 30 per cent. The bacteria can enter the body through surgical wounds, puncture wounds, burns, and minor cuts and scrapes. Early symptoms include redness, swelling, pain, blisters, fever, nausea, and vomiting. The infection progresses rapidly, leading to tissue death and causing severe pain, discolouration and peeling of the skin.

Flesh-eating bacterial infections have been documented for centuries, with some notable cases and outbreaks. Joseph Jones, a Confederate Army surgeon during the American Civil War, is credited with providing one of the first modern descriptions of necrotising fasciitis. He described it as “hospital gangrene”, a condition characterised by rapid and progressive soft tissue infection caused by Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, now recognised as necrotising fasciitis.

The term 'flesh-eating bacterial infections' is relatively new, coined and popularised by British tabloids towards the end of the 20th century to describe the necrotising infections caused by Group A Streptococci. Back then, the media suggested that epidemics of streptococcal infection were imminent. Scholars, however, note that such aggrandisement was unfounded. The moniker, though, helped in heightening public awareness of this infectious disease.

Diagnosing necrotising fasciitis involves a combination of physical examination, blood tests, tissue biopsy and imaging tests such as CT scans. Serious complications may lead to sepsis shock, organ failure, amputation and death. The infection can also cause severe scarring and long-term disability. Prompt and aggressive treatment is crucial, as necrotising fasciitis can rapidly progress and become life-threatening.

Treatment protocols include intravenous antibiotics, surgery to remove infected tissue, and other medications to manage complications such as sepsis and shock. Patients with underlying conditions like diabetes, immunosuppression, and chronic alcohol use are at higher risk and may require more aggressive management.