In July, American pharmaceutical giant Merck completed the $3 billion acquisition of a biotech firm named Eyebio. The deal included a hefty upfront cash payment of $1.3 billion.

The centrepiece of the acquisition was EYE103, a cutting-edge, antibody-based drug with remarkable potential to treat retinal diseases caused by vascular leakage, such as neovascular age-related macular degeneration (NVAMD), diabetic macular oedema (DME), and familial exudative vitreaoretinopathy (FEVR).

NVAMD affects over 200 million people globally, while millions more with type-1 or type-2 diabetes are at risk of developing DME. FEVR is a disorder that can lead to progressive vision loss. These conditions had no cures and EYE103 offers hope as a first drug of its kind. Its innovative antibody activates the Wnt-signalling pathway―a protein network that transmits cellular information―strengthening blood vessel integrity in the eye and preventing fluid build-up in the retina.

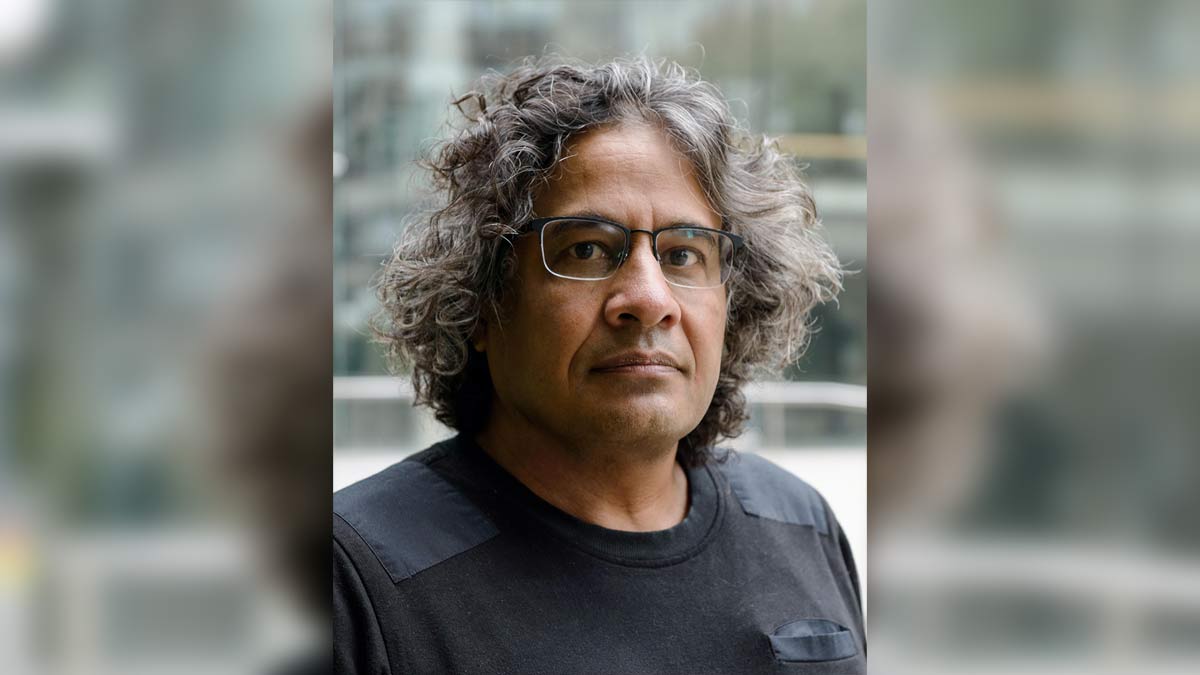

The antibody molecule in EYE103 is one of thousands of engineered antibodies―each with the potential to become future drugs for a range of serious illnesses, from cancer to rare diseases―originating from the lab of Canadian researcher Sachdev Sidhu.

The 55-year-old recently returned to his country of origin for an event. I met him for a tea-time interview at a bistro beside the serene artificial lake at the Taj Kumarakom Resort in Kerala. I was expecting a formally attired, jargon-spewing man of science. But, my preconceived notions were quickly shattered. Sidhu, the author of more than 200 scientific papers, a co-inventor on more than 50 patents granted by or filed with the US patent office, and a professor and entrepreneur-in-residence at the University of Waterloo, arrived in shorts and a round-neck T-shirt and ordered a glass of wine. In response to one of my early questions, he quoted American rapper Snoop Dogg.

“So, make all the ends you can make, because when you're broke, you break,” he said―referencing the lyrics of ‘Lil' Ghetto Boy’―to explain why he turned to drug and antibody research. “I did what I did because I had to survive. I don’t know if that’s the answer you want to hear, but I think there’s a bigger vision here. The vision is that I had to pay my rent.” As the conversation continued, Sidhu effortlessly wove in references ranging from Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky and American theoretical physicist Richard Feynman to basketball legend Michael Jordan.

Sidhu’s parents, who hailed from Punjab, migrated to Canada in 1970 when he was just a year old. “My mother was the first woman from her village to earn a college degree,” he said. “My father, a lawyer, was the first in his village to do the same. Then they moved to Canada. And guess what? Canada said, ‘Forget your degrees, you're going to work on farms.’ Imagine two of the smartest people I know, my mother and father, with college degrees they couldn’t use in Canada. Yet, it was the right decision because they did it for us.”

The family settled in British Columbia and Sidhu and his siblings joined their parents on the farms. All of Sidhu’s education, including his doctorate, was done from British Columbia. In a previous interview, Sidhu recalled his student days: “When I was in university, I avoided teachers! My job was to learn and to be independent.” This free-spirited approach carried into his research and entrepreneurial career, too.

For example, while the world was chasing Covid-19 vaccines, Sidhu and his team were working on an antibody therapeutic for Covid-19 symptoms. In early 2020, he designed a cell-based, virus-like particle antigen with the potential to serve as a therapeutic candidate for Covid-19, capable of treating the most severe symptoms of the infection. Sidhu's lab was among 47 research teams across Canada that received emergency federal funding to develop Covid-19 solutions. However, because of a lack of continued institutional support, the discovery remained in cold storage. “That’s one of the problems in Canada, too,” Sidhu said. “The antibodies were made, but they didn't bring them to the clinical stage.”

Sidhu’s team developed the Covid-19 therapeutic candidate within three months of getting federal funding. This rapid discovery had been backed by a technology in which he has been involved in for over two decades―“synthetic antibody libraries with man-made antigen-binding sites”.

Antigens try to invade your body. Antibodies search for them. Each antibody has a special key that fits perfectly into a specific antigen's lock. When an antibody finds its matching antigen, it locks on to it, blocks it and signals other immune cells to help destroy it. This teamwork helps one’s body stay healthy and fight off sickness. What Sidhu did was study antigen-antibody molecular interactions to develop highly functional repertoires that surpass the diversity and functionality of the natural immune system. He has also combined these special libraries with a system called phage display, enabling him to quickly identify antibodies that can match almost any antigen.

Antibody therapy has already shown tremendous success in treating cancer. Besides acting as markers for the immune system, antibodies fight cancer in three other ways. They can target and shut down signalling pathways on the cell surface, stopping cancer cell growth. They can activate signals that trigger the death of B-cell lymphomas. And they can deliver cytotoxic drugs directly to cancer cells. This makes antibodies more versatile than small molecules, another major class of drugs.

While discussing the potential of antibodies, Sidhu confidently said that no human disease was beyond treatment, and possibly even cure, with antibodies, as the focus was on modulating cell signals. “That's what the human body is―signals.” he said. “As soon as two cells interact, they have to signal. Now imagine 10 trillion cells doing the same. So yes, the potential is immense, and I won’t be humble about it. That’s the future.”

Sidhu and his team continue to innovate by developing new libraries and exploring advanced antibody formats, including single-chain and multi-specific antibodies that can target multiple antigens at once.

Sam Santhosh, an Indian entrepreneur and the founder of SciGenom Labs, which has incubated several biotech companies focused on genomics, said Sidhu’s success may be attributed to the fact that the antibodies developed from his platform are modular and can be engineered as building blocks to create many innovative products. “This has enabled Dev (Sidhu) to become a leader in creating multi-specific antibodies in various formats which will drive the next antibody revolution,” he said.

Sidhu started working on phage display libraries when he was with Genentech, the American firm which pioneered the biotechnology industry. His work and his many published scientific papers made him a well-known figure and by the late 2000s, the Donnelly Centre at the University of Toronto came courting―Canada was on a drive to bring accomplished scientists back to the country. It was around the time Santhosh met Sidhu.

“I met Dev in 2008, when I was planning to venture into genomics,” said Santhosh. “In that first interaction with him, it was clear to me that he was a genius, though I could understand little of his work. Over the next few years, as I focused on my efforts to leverage genome sequencing in India, I kept in touch with Dev. I also realized that genomics was powering a revolution in antibody development and that Dev was equally interested in what I was trying to do in India.”

Sidhu’s career blossomed at the University of Toronto. He got over $150 million in grants from the Canadian government and pharma companies to enhance his antibody platform and develop antibodies for various diseases. In 2015, he was awarded the prestigious Christian B. Anfinsen Award of the Protein Society for significant technological achievements in protein research. Many companies came to license Sidhu’s antibodies, but the transfer of technology from the university was a slow process and it frustrated the innovator.

“Around 2015, Dev felt that he needed a more focused effort to leverage the large number of antibodies in his library and started a unit called Centre for Commercialization of Antibodies and Biologics (CCAB) in the university,” said Santhosh. “As someone from the industry, he requested my support for the initiative. I joined as a director in the board of CCAB and we soon received a three-year grant for $15 million. Many companies such as Pionyr Immunotherapeutics (subsequently acquired by Gilead) and Northern Biologics came out of this effort.”

Santhosh, who closely observed Sidhu's career, noted that by 2020, the innovator began to take a different path. “Rather than simply providing his antibodies to pharmaceutical and biotech companies, he chose to become an entrepreneur and start his own ventures,” he said. “His goal was to further develop selected antibodies before licensing them. Over the next few years, Dev founded four companies, all of which secured significant funding and are at various stages of development.”

Notably, it is a molecule licensed by one of these companies, AntlerA, to EyeBio in 2021 that became the retinal regeneration drug acquired by Merck. Swiss giant Roche recently acquired AntlerA for an hefty sum. “When introducing Dev at conferences, I often half-jokingly say that he might be one of the first scientists to win a Nobel Prize and become a billionaire,” said Santhosh.

Although Sidhu left India as an infant and did not visit during his childhood, he was eager to reconnect with the country as an adult. Since 2011, he has been a regular visitor to India, attending scientific conferences. Sidhu is married to Sabrina Ramos, a Brazilian-origin entrepreneur who runs a clothing company called Aloja, which was inspired by her visits to India. She has taken many new-generation Indian designers to Toronto.

While Ramos took new-age Indian fashion labels to the west, Sidhu is focused on bringing cutting-edge antibody engineering from the west to India. “We can make drugs in India―drugs that the Indian public needs,” he said, adding that India, as a democratic country, is uniquely positioned to lead in high-tech fields, unlike the US, which he feels is dominated by Wall Street.

Santhosh said India missed the first antibody revolution. “Hence, most antibodies on the market are unaffordable for Indians,” he said. “They have to wait for patents to expire and then rely on Indian pharma companies to produce biosimilars. I hope we can collaborate with Dev to bring the next generation of antibody therapeutics directly to India―best in class and made in India.”