Between the news coverage, reportage and statistics around the ongoing Syrian civil war and the battle against Islamic State the firsthand experiences of ordinary civilians on the frontlines are difficult to source and expose. Yet these are often the very stories that can often provide crucial wartime evidence, chronicle social and historic shifts, or unearth true narratives that can counter official ones. And these stories are increasingly found on our bookshelves rather than on the newsstands.

From testimonies to short stories, graphic novels to memoirs, female writers, journalists and survivors are currently fronting the literatures of war, conflict and exile. The past two years have seen a surge of books and memoirs authored by women that capture the far-reaching human consequences of the Syrian civil war. Amid the fatigued reportage on its increasingly more complex escalations – and the cynical moves of other nations vested in opposing outcomes – these are compelling testaments to what befalls ordinary people as a consequence of fanaticism and powerful interests.

A remarkable example is Farida Khalaf’s 2016 memoir The Girl Who Beat ISIS. Khalaf and her family are Yazidis, members of a Kurdish-speaking minority who follow an ancient, pre-Islamic faith. The book recounts how Islamic State crossed the border into their mountainside village in northern Iraq, killing the men, recruiting the boys, and taking women and girls to slave markets in Raqqa.

Through testimonies of those such as Khalaf, the genocide against the Yazidis was officially recognised by the UN. Khalaf, in collaboration with German journalist Andrea C. Hoffmann, shaped their series of detailed interviews into a first-person narrative. Despite the indiscriminate violence visited on whole communities and towns, her memoir reminds that what women have suffered at the hands of IS, and what they continue to endure in refugee camps, is further devastating still.

Human consequences

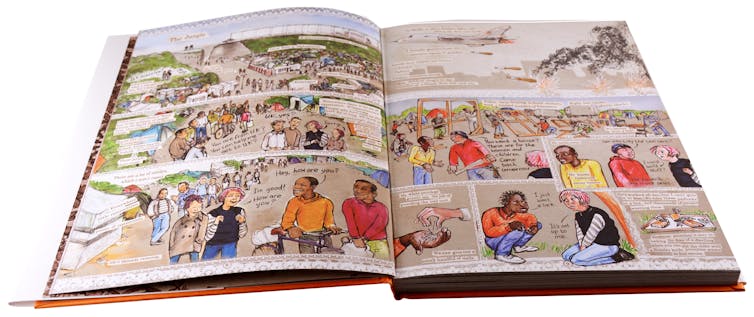

Kate Evans’ graphic novel, Threads: From the Refugee Crisis, though different in perspective and style, tells the stories of equally vulnerable people. Volunteering in Calais in 2015-2016, Evans bore close witness to the situation of asylum seekers in the so-called “Jungle”. Accustomed as we are to seeing quick news segments, these drawings are slow documentation at its best.

Its detailed visualisation of ordinary life under extraordinary circumstances enables Threads to vividly capture life in temporary shelters, the direct human consequences of European leaders’ political manoeuvres and the remarkable hospitality of those who have lost everything. Unafraid of checking her privilege and keeping refugees’ stories in the foreground, Evans depicts what reportage on Calais did not – indeed perhaps could not – capture.

Vivid testimonies

Interviews are often less depersonalising, but even they can sometimes ventriloquise already vulnerable voices. We Crossed A Bridge And It Trembled avoids this imbalance by presenting the direct testimonies of more than 300 Syrians living across the Middle East and Europe. American scholar Wendy Pearlman’s book gathers four years of firsthand narratives chronicling the Syrian rebellion, civil war and displacement.

The results unfold the extraordinary trajectory of the conflict in Syrians’ own words. The men’s accounts paint a vivid picture of life under Bashar al-Assad’s authoritarian regime, the build up of revolutionary momentum, and the devastation that followed. The female voices here, however, often transport the reader directly into these experiences. One young woman describes her first anti-regime demonstration in electrifying words:

I started to whisper, Freedom. And then I started shouting, Freedom! I thought to myself, this is the first time I have ever heard my own voice.

For some, finding the stories themselves comes with the highest of stakes. Having left Syria with her daughter in 2011 when the regime pursued her, writer and journalist Samar Yazbek secretly returned in 2012 hoping to set up a civic institution for women’s empowerment. The devastated homeland she found took shape into her latest book, The Crossing: My Journey to the Shattered Heart of Syria.

Yazbek’s account is a hauntingly good piece of literature – less than a decade ago, under vastly different circumstances, she was among Hay Festival’s top young Arab writers. Yazbek, although a longtime dissident, is an Alawite like the Assad family – so to travel in rebel-held regions and speak to jihadis, as she recounts doing, seems an almost suicidal undertaking. The Crossing is unforgettable when it thus entwines the personal and the political, as well as in its powerful lament: for girls snatched from childhood, and a homeland that has become unrecognisable.

All sides of the conflict in the region have entrenched the abuse of women. Dangerous journeys to Europe – and that often only to the limbo of refugee camps, rarely promise a way out. It recently came to light that humanitarian workers in Syria had been demanding sex from refugee women for UN food aid.

![]() The sad fact is that this is a body of literature that can only grow as the true costs of this war for women continue to mount. But these books are a vital start.

The sad fact is that this is a body of literature that can only grow as the true costs of this war for women continue to mount. But these books are a vital start.

Sarah Jilani, PhD Student, Faculty of English, University of Cambridge

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.